This is how I remember it.

The 1970s in Sweden was a period when activism was easy. The welfare state was still strong and unquestioned, with the possible exception of those who actually benefited from its generosity. Raising funds for different kinds of collective and cultural activities was not difficult: the government, local authorities, and others such as adult educational associations favoured many kinds of initiatives. Thus, for instance, local authorities offered—without charge—space for gatherings such as seminars for study groups, or rehearsals for amateur plays. Many schools were open after hours for almost anyone who could produce some kind of plan or affiliation to an organization. Not only public authorities, but even organizations such as labour unions had their heyday of prosperity and influence, and it was common for them to encourage cultural and collective enterprises. That is, culture was all, and ‘alternative’ (‘non-commercial’), vaguely leftist cultural expressions were preferred.

One of the central concepts in circulation was ‘criticism’, deriving from a variety of theoretical and political (Marxist) sources, such as the Frankfurt school, which had been introduced in academia and political study circles in many places. In the aftermath of the expansion of the 1950s film club movement—with its origins in fan cultures—criticism was a notion naturally adapted in film culture as well. In addition, the profession of a film critic developed from women, film and agency in the 1970s and 1980s its early function to the point where ‘anybody could write criticism’ and soon gain an air of authority and poise.[1]

Critics and criticism from different areas of the same field could conflict fiercely with each other, as happened between the members of the feminist movement, who insisted on more power for women in the film industry, and the film critics in the daily press. As will be seen, the critics could be blamed for betraying their critical assignment and being blind to, if not supportive of, the obvious machismo and sexist portrayals of women in film. This was particularly obvious in regard to the many coming-of-age films that were produced by the new generation of filmmakers in 1970s Sweden. The choice of target genre is striking, though, since this was a period when a large number of porn films were produced in Sweden as well. One might think that due to their blatantly debasing treatment of the female characters, the porn industry would be a given target for (women) film activists. Yet this was not the case. It is therefore possible to speculate that the public debate of the mid-1970s was not as much about machismo as it was about the privilege of being able to tell the coming-of-age story of the new post-war generation, a generation unlike any other.

The organization

Many associations and interest groups were established in the 1970s, including the Swedish Women’s Film Association (SKFF, Svenska Kvinnors Filmförbund). Other organizations with interest in films and film production were established as well, for instance Tensta Film Association (Tensta Filmförening) in 1974 and the Film Workshop (Filmverkstaden) in Stockholm in 1973. Some organizations were founded by immigrants—from Southern Europe or Latin America, for example—such as Cineco, founded in 1976, the same year that SKFF was officially registered.[2]

Regarding SKFF, a few embryonic groups for the exchange of ideas on film existed before its official registration, started by women with backgrounds in journalism, national television (until 1978 called Sveriges Radio, SR), film production at the Swedish Film Institute’s Film School (Filmskolan, from 1970 the Dramatic Institute)—or cinema studies at Stockholm University. Not all members were filmmakers or filmmakers in spe; some were interested in an academic career or in film journalism. Some SKFF supporters were just activists involved in promoting women’s issues across all fields of society, including film. However, a majority of the founding and future members of the association were either employed in different positions at the public television or freelance film workers. Often they were organized by FilmCentrum (an association for independent filmmakers established in 1968) or the Film Workshop, run by the Swedish Film Institute (SFI) and SR to support ‘unestablished’ film workers in their ventures.[3]

The groups that were to form the SKFF recruited wherever people interested in film got together: at the meetings of FilmCentrum, in SR’s staff lounge, or in the foyer of the Film House (Filmhuset). As for myself, I was recruited during a break between two lectures by my fellow student Pia Kakossaios, and in 1975 I joined a production group, even though I was not that interested in film production. Margaretha Wästerstam and Märit Andersson were leading members of the group because of their competence and vast experience of television and documentary. I also remember the Norwegian Bibbi Moslet, later a dramaturge at the National Opera in Oslo, the future authors Gunilla Boethius and Agneta Klingspor, and the photographer Maria Bäckström participating in meetings during this pre-SKFF period.

Far from all women engaged in film production—or film criticism for that matter—were interested in membership of the SKFF. Many women were busy working on their careers, and left-oriented film politics were not everyone’s priority. A handful of resourceful women did indeed navigate the film industry successfully. But its structure, reminiscent of a mediaeval guild system in which each master had his apprentice, having himself been trained in the profession by an earlier master, made it very difficult for women to push through.[4]

The increasing number of (government-supported) bodies offering opportunities for film-making did not make much difference for women, at least not when it came to gaining positions as film directors. And as a woman, it was equally difficult to find a job as a cinematographer. In the three year period that this survey covers, there was not a single feature-length film shot by a woman. Three women, Marianne Ahrne, Mona Sjöström, and Maj Wechselmann, were credited as directors of feature-length films in 1974–1976: Wechselmann and Sjöström directed documentaries screened in cinemas, and Sjöström only as a co-director with Ulf Hultberg of two documentaries on Ecuadorian women.

Women’s careers seemed to find their highest peak in such ‘supporting’ professions such as scriptwriters, production assistants, film editors, script supervisors, and TV producers. Some female TV producers actually did direct features and series. But at the time it was as if this did not count either. Television did not have the same cultural status as the cinema, and to be valued as a director you had to have created a strip of celluloid and demonstrated mastery of the feature, shown in a cinema.

The ideals

The valorization of cinema over television had several reasons. One was the overarching ideology based on auteur theory and its common interpretation, which considered the position and artistic views of the director to be crucial for a film’s construction and meaning. This would be one of the major features in defining the Art House film-making that was promoted by the Swedish Film Institute and its leadership in the 1960s and 1970s.[5] A film director was regarded as a writer, an author of stories; as a unique individual, faithful to his values and opinions and eager to express his (or—more rarely—her) world view.[6] The film director’s pen was the camera. Essentially, a film director should master the tools of film-making—and be responsible for the entire production process.[7] Such ideas were debated and best articulated in the film magazine Cahiers du Cinema throughout the 1950s, and the film director as an auteur made a conspicuous entry at the international film festival in Cannes in 1959.

Swedish critics and film workers became deeply impressed by the French generation of 1959, as were the rest of the world. Auteur theory involved the figure of a critic as well. The role of the critic was to be the expert to ‘explain the meaning and value of the work of an auteur in a mutual system of dependency and admiration’.[8] Mariah Larsson has shown how a small circle of men around the CEO and founder of the Swedish Film Institute, Harry Schein, created a hands-on policy that reflected their understanding of the notion ‘culturally valuable film’ and how this kind of film was ideally produced: by a (male) auteur.[9]

Bo Widerberg, Jan Troell, and Vilgot Sjöman were among those who were to consolidate their position in terms of auteurism in the 1960s, as did Mai Zetterling—with her four feature films, the only Swedish woman to make a name for herself as an auteur in the period. Ingmar Bergman, standing on the shoulders of his mentors such as Alf Sjöberg, Lorens Marmstedt, and a few others was, in a sense, isolated in a category of his own. At this point he was already a world famous, financially independent ‘persona’, but in Sweden also genuinely non grata, especially among the younger generation of leftist cultural workers.[10]

The second, compelling factor in the pursuit of a position as a film director would have been a righteous quest to make oneself heard. The item that perhaps best condenses the sentiments of this period of the feminist enterprise in Sweden is an LP from 1971 made in the studios of Musiknätet Waxholm (later MNW Music) with the title Sånger om kvinnor (‘Songs about women’). This collection of songs had been assembled on the initiative of an action group called Grupp 8 (Group 8) and was based on a long-running stage play Tjejsnack (‘Girl talk’) directed by Suzanne Osten and Margareta Garpe for Stockholm City Theatre. One of the songs on the album had a chorus, ‘Oh, oh, oh girls, we must raise our voices to be heard!’[11] Sung to a march-like, up-beat tune with emphasis on the first syllable of each word, it is the essence of the entire movement: the sound and strength of a woman’s raised voice, on its own or as a group of voices, was the means to articulate both identity and goals.[12] A call to breathe deeply, raise your voice, and make yourself heard would provide a position in society at large. A position meant a place, a point of view, and, hence, a relation to the others, which as we know is the basis of identity.

The film movement of the 1970s generation that SKFF was a part of struggled with a number of contradictions and double binds, most of which remained unsolved, perhaps even unrecognized. Most likely, this was part of the reason why the movement did not quite fulfil its goals and expectations. In the field of film and production, there was (and arguably still is) a demarcation line between those who were on the ‘inside’, established at major theatres and in the film industry, and those who were on the ‘outside’, either aspiring to positions on the inside, or wanting to stay outside large institutions for political reasons. The latter were strongly critical of government-supported film policy and the politics of the SFI.[13] But as already noted, they still applied and received funding for their film projects from the very sources they so harshly criticized—an unhappy situation for all concerned.

On the one hand, it was important to stress that film was a collective enterprise, and many overtly politically conscious film directors preferred the professional title of ‘film worker’ to that of film director. But on the other hand, many filmmakers aspired to sole artistic leadership exercised by one person. Such a pseudo-democratic state of affairs inevitably created organizational problems on set, with personal conflicts sparked by confused boundaries between different functions, and, as a corollary, frustration and loss of energy.[14]

The SKFF activists had yet another project to handle, not directly contradictory but rather bidirectional: embedded in the quest for the position of film director was a concern about what was perceived as unrealistic, stereotypical images of women in film. The argument went that if women were ‘allowed’ to direct films, the images of women on the silver screen would be more in line with truth—recognizable thanks to the experiences of the many. This, of course, had been a key argument of the international feminist movement since the early 1960s.[15] Criticism of female images was not only directed at film producers, but also at the ‘receiving’ part of the communication model—the film critics and journalists. Activist women in the SKFF and elsewhere expected film critics to condemn the unrealistic portrayal of women in film, and to insist on more rounded characters, preferably created by women. In other words, the women interrogating the field of film production expected the film critics to support their initiative. The exact reasoning that prompted this expectation is obscure, but, as has been suggested above, it probably had to do with how the notion of criticism itself was understood. If the SKFF activists perceived themselves as critical of the status quo, then all (film) critics were expected to share their standpoint. A non sequitur, of course.

The output

The early 1970s witnessed a slew of coming-of-age stories, in this case the tales of the generation born in the 1940s. Two novels that were very successful and had a lot of publicity are of particular interest to my discussion, because they were both adapted into films almost immediately after their release, in the first flush of critical and financial success. One was Jack, written by the Swedish pop singer and author Ulf Lundell, a book on ‘how it feels to be young in the 1970s Sweden’, released in 1976. Lundell’s tremendous success was however preceded by Det sista äventyret (‘The Last Adventure’) written by Per Gunnar Evander in 1973.

Evander was a schoolteacher, a few years senior to the generation born in the 1940s. Before publishing Det sista äventyret he had directed four films. With this novel, he hit a nerve. This was a story in line with films such as Family Life (Loach, 1971), A Woman Under the Influence (Cassavetes, 1974), and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Forman, 1975)—all loosely connected with the public interest in psychotherapy and self-help books such as Arthur Janov’s Primal Scream (1974) and David Cooper’s The Death of the Family (1971). The psychoanalyst Alice Miller’s theories of oppressive family patterns and children’s self-destructiveness formed a background for stage plays as well as therapy sessions. Freedom was another core notion, and Erich Fromm’s Escape from Freedom (1941) was listed as course literature even in Cinema Studies.

Det sista äventyret is the story of a young, sensitive man, Jimmy, oppressed by his family and dismissed from compulsory military service as a misfit. He has a love affair with a pupil, Helfrid, at a school where he works as a substitute teacher. As the relationship falters because of Helfrid’s infidelity, Jimmy has a breakdown and ends up in a mental institution. The story closes on a marginally more positive note as Jimmy and another mental patient admire the beautiful view of the lake. Ann Zacharias—who in spite of her youth already had appeared in French porn films—plays Helfrid. Jimmy’s part was shouldered by Göran Stangertz, a baby-faced actor very popular in this particular period. Stangertz also went on to play Jack, the protagonist of Lundell’s eponymous novel, which was adapted shortly after the book’s publication in 1976 and had its premiere in 1977.

The preparations and shooting of Jack were the source of much gossip. It was said that Lundell himself would be ‘allowed’ to direct the film. However, Janne Halldoff, the director of Det sista äventyret, was recruited to direct Jack. Halldoff came from a middle-class family, and had been an amateur photographer since he was a child. He was quite a productive director, and had made sixteen feature films in the ten years before Det sista äventyret. He had a reputation for being an easy-going guy whose films were equally easy-going, thematizing the notion of freedom in films portraying groups of young men, with an approach similar to films like American Graffiti (Lucas, 1973) or The Graduate (Nichols, 1967). Characteristically, Halldoff’s next film project after Det sista äventyret was called Polare (‘Buddies’, 1976).

Det sista äventyret was considered Janne Halldoff’s comeback. He had not been successful with any of his six films in the first half of the 1970s. Det sista äventyret opened on 24 October 1974, and the critics were almost unanimously positive, hailing the story as well as the photography and casting as excellent. Both Ann Zacharias and Göran Stangertz got positive comments: Stangertz for his acting skills (the following year he would receive a Guldbagge, the Swedish equivalent of an Academy Award, for best leading male actor), Ann Zacharias for her good looks. Hanserik Hjertén, the leading film critic in the country’s largest morning paper, Dagens Nyheter, described her as a ‘Skogsrå i pessarålder’, literally ‘a nymph of diaphragm-using age’, which apart from reducing the actress to a sexual object signalled to the reader that she looked (and was) very young.[16]

Hjertén was a decent man and a highly regarded film critic. But his comment about Ann Zacharias was one of those expressions that took on a life of its own in the press, and surfaced any time Zacharias got attention in the press, which happened a great deal in 1975. The number of buddy movies and novels in circulation, together with the rumours and publicity surrounding Jack’s production, confirmed the SKFF members in their view that film politics, and indeed the entire system of film production in the country, was biased towards men—particularly young men. Halldoff not only directed, he shared the scriptwriting with Lundell. This was clearly an example of buddies helping out buddies. SKFF meetings rang with angry voices. They wondered, rightly, when the stories of young women would be told, and who would be ‘allowed’ to tell those stories without a stereotyped young woman seducing a young man just in order to betray him.

The debates

On 28 January 1976 another film, Hallo Baby (‘Hello Baby’) had its premiere. The film was a collaboration by the painter Marie-Louise Ekman (née Fuchs, later De Geer) and her then husband Johan Bergenstråhle. She was responsible for the script, set, and costumes, and also played the leading character, Flickan (the Girl), in the film. In fact, Hallo Baby was later frequently credited to her rather than to Johan Bergenstråhle, probably because of the overall presence of her artistic style. With its colouring, characters, settings—indeed, its entire cinematic universe—this film would contribute to the future branding of Marie-Louise Ekman in film and other media.

Hallo Baby was daring, and featured both male and female nudity. Among other things, it exposed the intimate body parts of its leading lady, seven-months pregnant, dressed in a tutu, as she bends over a windowsill, wearing no underwear. Even in the liberal 1970s (out of 69 feature films made in Sweden in 1974–1976, 19 were porn films) the film was received with mixed feelings. Initially, the critics were divided between those who considered the film a brilliant reflection on modern sentiment (Åke Janzon) and those who saw in it a hideous piece of celebrity exhibitionism (Jurgen Schildt).[17] Birgitta Bergmark, a TV producer, soon initiated a debate in Aftonbladet, presumably after contacting Schildt, who was the paper’s film critic. Bergmark opined that Hallo Baby was just another example of the contempt of women, depicting them in particularly spiteful terms.[18] Another view was presented by the author Åsa Moberg, who held that the film’s all encompassing irony—fashioned in excess, colouring, and the use of camera— presented some thoughtful criticism of familiar stereotypes.[19] The debate was to continue through February and into March.

Misogyny in film had been discussed earlier, of course, as Gun-Britt Sundström, a columnist in the liberal daily Dagens Nyheter noted. Thus, for example, in 1974 Ingmar Bergman and his favourite actor Erland Josephson were targeted for the images of women in Bergman’s 1972 film Cries and Whispers (Viskningar och rop).[20] However, it was probably the heated debate about Hallo Baby and the continuing anger at ‘buddy productions’ that led SKFF members to ask my fellow students Giesela Appelgren and Elise Jonsson and me if we might be interested in looking into contemporary film criticism and the ways in which it discussed female characters. Yes, we were. One of the assessments in the Cinema Studies undergraduate programme at Stockholm University was to present a lengthy written report. This would be a perfect topic. SKFF’s membership decided that the report should be used as the basis for a hearing arranged in cooperation with the Journalist Club of Stockholm.

The hearing took place on 8 November 1976 in ABF-huset (ABF House), a building owned by the Workers’ Educational Association, the largest such venue in the country. The title of the hearing was ‘The woman in film criticism’. Several well-known film critics from some of the major dailies agreed to participate in the panel (Jurgen Schildt from Aftonbladet, Hanserik Hjertén from DN, Jonas Sima from Expressen, and SKFF member Maria-Pia Boethius, also from Expressen). Also participating were Ann-Katrin Agebäck, a student advisor at Stockholm University, who would later be a member of the government authority for film censorship, as well as the actress Gunnel Lindblom, known for her roles in many of Ingmar Bergman’s films. She was to release her first feature-length film as a director, Summer Paradise (Paradistorg), a few months later in 1977.

The three of us presented the results of our study. And just to be clear, the study we presented was poorly executed. It consists of nineteen sparsely written pages and is quite biased. The report has the same title as the hearing, ‘The woman in film criticism’, and presents excerpts from a number of film reviews published in 1974–1976.[21] We had been looking for whatever annoyed us, which meant that at best the report could be called an inductive study—a collection of material for developing a thesis to be tested later. In other words, while practising criticism of the cultural conditions of our time, we forgot to criticize our own project. The report, while it does present its sources, fails to answer the question of the representativeness of the samples used. The survey refers to a total of twenty-five films, including both Swedish productions and foreign imports, but it is hard to ascertain what the principles of selection had been.

It should be noted that films such as Ingmar Bergman’s adaptation Scenes from a Marriage (Scener ur ett äktenskap, 1974) and The Magic Flute (Trollflöjten, 1975), Vilgot Sjöman’s A Handful of Love (En handfull kärlek, 1974) and Garaget (‘The Garage’, 1975), Bo Widerberg’s Fimpen (‘The Butt’, 1974) and Man on the Roof (Mannen på taket, 1976) were not included in the survey. Of course, in the 1970s a student’s access to feature films was limited to those titles that were on release in the city cinemas or shown at the Cinemathèque. However, the reviews of films that we had not been able to see must have been accessible. Also, it is hard to understand how the study—and the entire debate—managed to totally ignore the fact that only weeks before Marianne Ahrne had been the first woman ever to receive the Best Director Guldbagge for her 1976 film Långt borta och nära (‘Near and Far Away’). Thus, it is plain that the aim of the survey was not to critique the films directed by well-established directors, but those with a status more on a par with the women aspiring to the position of film director—their possible rivals, in other words.

The cover picture of the report is very revealing as a statement that confirms the thesis of the survey. It depicts a naked woman sitting on her knees with her hands and hair cast back, blood running across her right breast. In front of her stands a laughing man in a white tuxedo, holding a gun. The picture is a convincing example of a woman being subjected to deadly violence by a man, and she is, undoubtedly, an object of the spectator’s voyeuristic gaze as well. However, the picture is from Hallo Baby, a sequence from a film-in-a-film that was clearly critical of the porn industry and the way it treats women. Was it fair to strip an image from its context and use it for our own purposes? The simple answer is no.

The report also gives a brief account of the hearing itself. At the event, the students (the three of us) described the findings of the survey, after which an intense and sometimes heated discussion took place. Hanserik Hjertén’s description of the character Helfrid in Det sista äventyret was singled out. Hjertén was deeply unhappy and apologized for using an expression that reduced the actress to an object of sexual fantasy. Ann Zacharias, who played the role of Helfrid in the film, was sitting in the first row in the audience and said that she did not mind at all. Some of the critics were quite defensive though, and especially Jurgen Schildt, who held that after all, it was impossible to please everyone when it came to the task of evaluating an artistic product—‘should the devil be a film critic?’ he asked.[22] Actually, the film critics present did not come in for much criticism, as the discussion took a more general turn when most of the panel and the audience agreed that the number of female film critics was too low. More women in the field, it was reasoned, would probably change the mode of criticism for the better.

The event resulted in a written resolution sent to the editors of all the major newspapers demanding that they engage more women in film journalism. It is also worth noticing that in the mid-1970s, on a chilly night in November, an audience some 120 strong had turned up to this event. A hearing like this, with a minimum of advertising, arranged by a small, newly established group of women, and based on a report written by three undergraduate students, managed to get well-known, even famous, people to participate. The occasion was open for anyone interested and—a prerequisite for such an event in Stockholm, like the hire of the auditorium itself—free of charge.

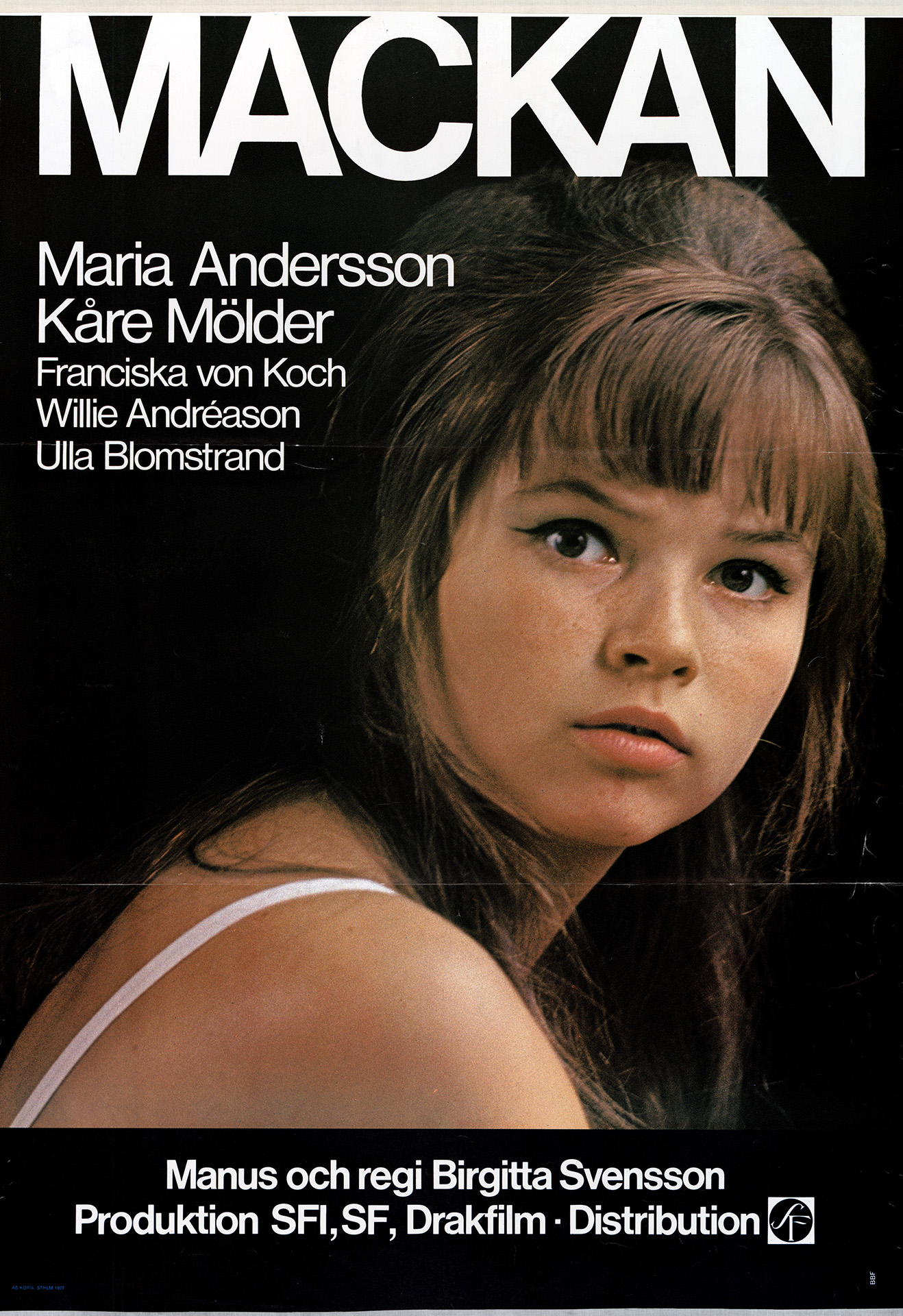

On 25 January 1976, three days before Hallo Baby opened in cinemas, the Norwegian director Anja Breien’s film Wives (Hustruer, 1975) had its Swedish premiere, which passed without much notice. Gunnel Lindblom’s film Summer Paradise opened in February 1977 and received quite positive reviews, as did Långt borta och nära by Marianne Ahrne. The first coming-of-age film portraying a young girl from the 1960s generation premiered in December 1977. The film was called Mackan and was directed by Birgitta Svensson. The reviews, mostly by male critics, were devastating. This did not pass without protest, however. A handful of responses were published, pointing out what was considered unfair treatment because of the director’s gender.[23]

The aftermath

Nearly half a century has passed. Having lived at a particular time in a particular place, I have told a story of a feminist action in which I played a small part. While weaving my reminiscences into a narrative, I realized I was not only looking back at the action and the images that remained in my head, I was also looking for material—reviews, interviews, and historical accounts to create a context to support these images and reminiscences. In looking back, the work seems to resemble the one described by Annette Kuhn in her Family Secrets. She writes that ‘Memory work has a great deal in common with forms of inquiry which involve working backwards, searching for clues, deciphering signs and traces, making deductions, patching together reconstructions out of fragments of evidence.’ In addition, it is worth stressing that when the past is penetrated by the present, the ‘patching together’ produces an analytical—or rather, an explanatory—discourse, which I hope may be discerned here. And of course, this essay is not the last word because, by putting an end to my story, I yield it to others. Or as Annette Kuhn would put it, ‘Clearly, if in a way my memories belong to me, I am certainly not their sole owner. All memory texts constantly call to mind the collective nature of the activity of remembering.’[24]

Tytti Soila

This text was first published in Making the invisible visible: Reclaiming women’s agency in Swedish film history and beyond, ed. Ingrid Stigsdotter (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2019), 121-137.

Notes

1. Jurgen Schildt, cited in Appelgren et al. 1976, 17. In this essay, I cite in the endnotes the sources I believe to have contributed to my composition of the ‘memory-image’ of the issue.

2. Nilsson 1989, 29–30.

3. Svenstedt 1971, 45.

4. Soila 2004, 12 ff.

5. Larsson 2006, 59 ff.

6. Luthersson 1986, 386.

7. Astruc 2009, 32.

8. Caughie 2001, 12 ff.

9. Larsson 2006, 52.

10. Bergom-Larsson 1977, 152–3.

11. ‘Oh Oh Oh tjejer, vi måste höja våra röster för att höras!’

12. Nilsson 1989, 34–5.

13. Svenstedt 1971, 100–109.

14. Soila-Wadman 2003, 14–15, 23–6.

15. Kuhn 1982, 84 ff.; Rich 1998, 71 ff.

16. Hjertén 1974, 22. At this time, the diaphragm was the contraceptive of choice for young women, whereas older women used the pill.

17. Janzon 1976, 11; Schildt 1976.

18. Bergmark 1976.

19. Moberg 1976.

20. Sundström 2016, 50. Editor’s note: for films with an official English-language title, the original title is listed in brackets when first mentioned and the official translation is used throughout the text. For films that do not have an official English-language title, an English translation of the title is given when first mentioned and the original title is used throughout the text.

21. In Swedish ‘Filmkritikens kvinna’; Appelgren et al. 1976.

22. In Swedish ‘ska fan vara filmkritiker’.

23. Soila 1977.

24. Kuhn 1995, 4–5.

References

A Handful of Love/En handfull kärlek (dir. Vilgot Sjöman, Sweden, 1974).

A Woman Under the Influence (dir. John Cassavetes, US, 1974).

American Graffiti (dir. George Lucas, US, 1973).

Andersson, Lars-Gustaf & John Sundholm, Research seminar presentation on amateur films on the 1970s, spring 2017, Department of Media Studies, Stockholm University.

Appelgren, Giesela, Elise Jonsson & Tytti Soila, ‘Filmkritikens kvinna’ (Final report 2nd semester, Institutionen för teater- och filmvetenskap, Stockholms Universitet, 1976).

Astruc, Alexandre, ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Style’, in Ginette Vincendeau & Peter Graham (eds), The French New Wave (London: Secker & Warburg, 2009).

Bergmark, Barbro, Aftonbladet, 30 January 1976.

Bergom-Larsson, Maria, Ingmar Bergman och den borgerliga ideologin (Stockholm: PAN/Norstedts, 1977).

Caughie, John (ed.), Theories of Authorship (9th edn, London: Routledge, 2001).

Cooper, David, Död åt familjen (Stockholm: Aldus/Bonnier Förlag, 1971) (first pub. as The Death of the Family, 1971).

Cries and Whispers/Viskningar och rop (dir. Ingmar Bergman, Sweden, 1972).

Det sista äventyret (dir. Jan Halldoff, Sweden, 1974).

Evander, Per Gunnar, Det sista äventyret (Stockholm: Bonnier Förlag, 1973).

Family Life (dir. Ken Loach, UK, 1971).

Fimpen (dir. Bo Widerberg, Sweden, 1974).

Fromm, Erich, Escape from Freedom (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1941).

Garaget (dir. Vilgot Sjöman, Sweden, 1975).

Hallo Baby (dir. Johan Bergenstråhle, Sweden, 1975).

Hjertén, Hanserik, ‘Nu övertygar Jan Halldoff’, Dagens Nyheter, 25 October 1974.

Jack (dir. Jan Halldoff, Sweden, 1977).

Janov, Arthur, Primalskriket (Stockholm: Wahlström & Windstrand, 1976) (first pub. as Primal Scream, 1974)

Janzon, Åke, ‘Ungdomens gåtfulla liv’, Svenska Dagbladet, 29 January 1976: 11.

Kuhn, Annette, Women’s Pictures: Feminism and Cinema (London: Pandora Press, 1982).

—— Family Secrets: Acts of Memory and Imagination (London: Verso, 1995).

Långt borta och nära (dir. Marianne Ahrne, Sweden, 1976).

Larsson, Mariah, Skenet som bedrog: Mai Zetterling och det svenska sextiotalet (Lund: Sekel Förlag, 2006).

Lundell, Ulf, Jack (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1976).

Luthersson, Peter, Modernism och individualitet: En studie i den litterära modernismens kvalitativa egenart (Lund & Stockholm: Symposion, 1986).

Mackan (dir. Birgitta Svensson, Sweden, 1977).

Man on the Roof/Mannen på taket (dir. Bo Widerberg, Sweden, 1976).

Miller, Alice, Das Drama des begabten Kindes (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1978).

Moberg, Åsa, Aftonbladet, 4 February 1976.

Nilsson, Karl-Ola, ‘“Förnekar ni historien, drar vi igen den”: Om 1970-talets dokumentärfilm’, in Lars Åhlander (ed.), Svensk filmografi, vii: 1970–1979 (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1989).

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (dir. Miloš Forman, US, 1975).

Polare (dir. Jan Halldoff, Sweden, 1976).

Rich, B. Ruby, Chick Flicks: Theories and Memories of the Feminist Film Movement (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1998).

Scenes from a Marriage/Scener ur ett äktenskap (dir. Ingmar Bergman, Sweden, 1974).

Schein, Harry, ‘Det hände på 60-talet’, in Jörn Donner (ed.), Svensk Filmografi, vi: 1960–1969 (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1977).

Schildt, Jurgen, Aftonbladet, 29 January 1976.

Soila, Tytti, ‘Mackanfilmen illa behandlad’, Dagens Nyheter, 30 January 1977.

—— Astrid Söderbergh Widding & Gunnar Iversen, Nordic National Cinemas (London: Routledge, 1998).

—— Att synliggöra det dolda: Om fyra svenska kvinnors filmregi (Stockholm & Stehag: Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposion, 2004).

—— Private archive notes and minutes from the meetings of SKFF 1975–1985.

Soila-Wadman, Marja, Kapitulationens estetik: Organisering och ledarskap i filmprojekt (School of Business Research Reports 1400–3279; Stockholm: Stockholm University, 2003).

Summer Paradise/Paradistorg (dir. Gunnel Lindblom, Sweden, 1977).

Sundström, Gun-Britt, Klippt och skuret: Kåserier (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2016).

Svenstedt, Carl Henrik, Arbetarna lämnar fabriken (Stockholm: PAN/Norstedts, 1971).

The Graduate (dir. Mike Nichols, US, 1967).

The Magic Flute/Trollflöjten (dir. Ingmar Bergman, Sweden, 1975).

Wives/Hustruer (dir. Anja Breien, Norway, 1975).