Folkekomedie, which literally translates folk comedy, encompasses genres such as homeland films, sentimental comedy, farce and family comedy, as it draws on the culturally recognizable and relatable in Danish character types, traditions, customs, parlance and landscape. (Hartvigson IV and V). The academic blindness to her qualities notwithstanding, her Saga films from Den gamle mølle paa Mols (The Old Mill on Mols, 1953) to Baronessen fra benzintanken (The Baroness from the Gas Station, 1960) and Frøken Nitouche (Mam’zelle Nitouche, 1963) continue to enjoy a prominent position in the popular canon (Hartvigson II). Reenberg is a masterful interpreter of the popular and her films’ continued popularity is no doubt connected to her flair for and acute understanding of folkekomedie’s potential and her ability to grapple with our dreams and the norms we live by in a context of tradition, the quaint and the well-known.

Career

Annelise Reenberg started as a still photographer at the Burmeister og Wain shipyard in 1943, before she was hired as plate photographer and cinematographer’s assistant at Saga Studio under chief cinematographer, Aage Wiltrup. However, it was production leader Poul Bang, whom she married shortly before his death in 1967, who with his practical and unsophisticated approach to film work became a mentor for the relatively inexperienced Reenberg, who moreover had to combine her aesthetic sensitivity to popular output of the Saga Studios. In 1946, they left Saga together for Nordisk Film, where Reenberg received highly profiled assignments on fiction films and documentaries with extended creative responsibility. When she and Bang returned to Saga in 1949, she quickly became the folkekomedie studio’s leading director, a position she kept until her retirement in 1971. In the fifties, the homeland genre dominated the cinemas, and with Historien om Hjortholm (The Story of Deer Islet, 1950) shot and co-directed by Reenberg, Saga launched its distinct and stylistically striking series of homeland films. Coincidentally, Reenberg’s fifties homeland films were in direct competition with the Morten Korch adaptations from ASA overseen by Denmark’s first female director, Alice O’Fredericks. In the sixties Reenberg’s films moved in the direction of romantic and family comedy, and in 1966 she launched the popular series Min søsters børn (My Sisters Kids series 1966-71).

In the sixties and seventies folkekomedier and family films were still the preferred Danish genres by the public, but the commercial film industry was severely pressured by the competition from television, the cinema crisis and the new film laws and economic aid schemes, which preferred and supported realism and art films. At Saga, a number of reorganizations were carried out, and it was in connection with these that Annelise Reenberg retired at the age of fifty-three. Apart from growing difficulties achieving commercial success with folkekomedie, other deciding factors for her early retirement were likely the recent death of husband, confidant and collaborator, Poul Bang and that she, as she put it herself, was set in her ways and reluctant to change her work habits (Pedersen II).

Denmark’s first female cinematographer

From her feature debut as cinematographer with En ny dag gryer (The Dawn of a New Day, 1945) Annelise Reenberg was praised for her beautiful and evocative work as well for her status as the country’s only female cinematographer. In the following years, journalists were very attentive to the apparent paradox of the small feminine woman – which she was not really – and the responsibility, long hours, and “all the heavy lifting”. In relationship with the press, Reenberg was extremely private, and her interviews presented prepared generalities about good working conditions at Saga and the importance of a relaxed tone during shooting with quaint anecdotes thrown in to give an impression of spontaneity. She never mentioned her emotional life, but this did not stop her films from being interpreted as being the result of amorous longings, childhood trauma or fight for women’s rights. Speculations about her personal life were surely fueled by the fact that she was the child of beloved royal actor Holger Reenberg and half-sister of actor Jørgen Reenberg and singer Elga Olga Svendsen, and the fact that she remained unmarried until very late in life.

Artistic breakthrough

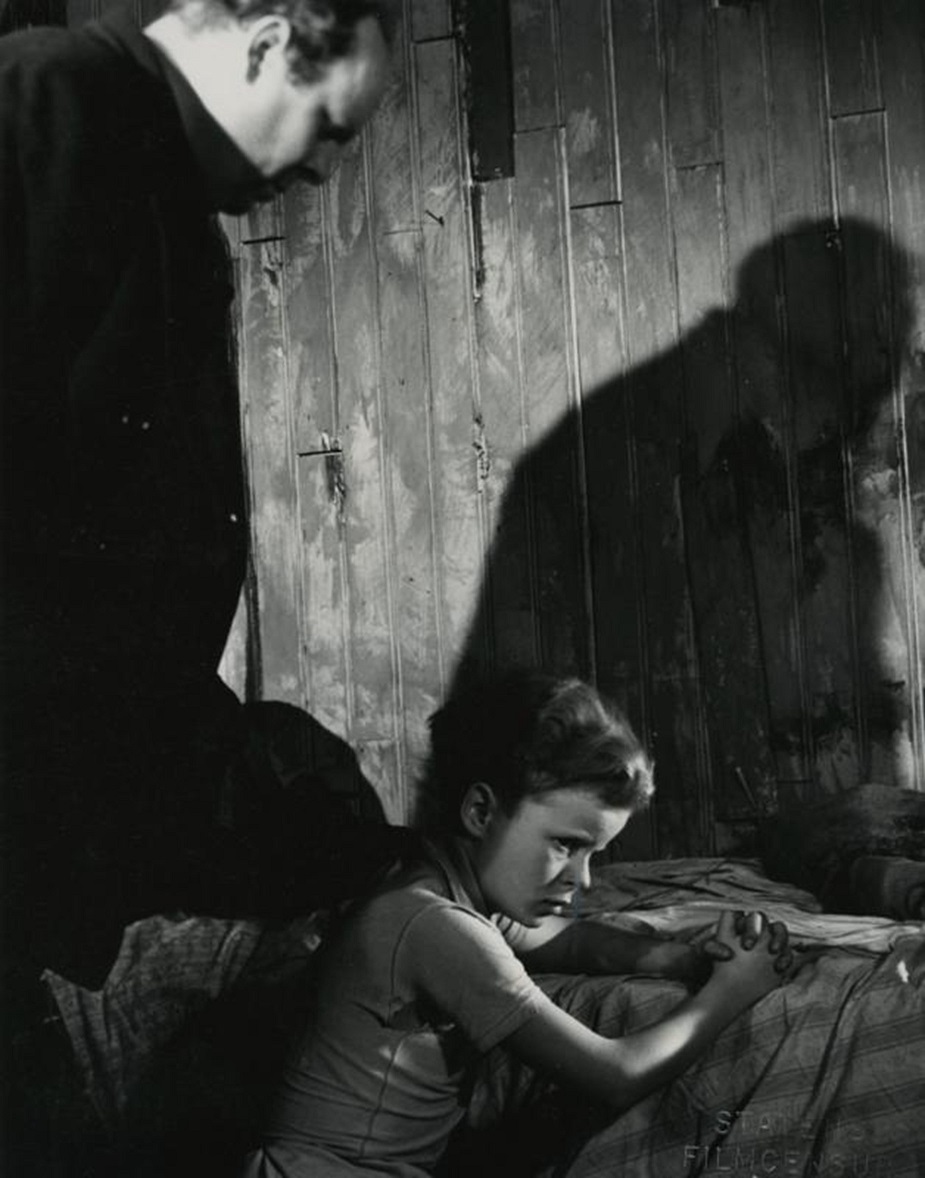

Saga was a studio of farce, comedy and folkekomedie presided over by John Olsen with his famed gut feeling for what the audience wanted, but it had come close to losing it’s production license due to films of “inferior quality” in 1947 (Dinnesen and Kau). Annelise Reenberg’s temperament and flair for the aesthetically refined was not an obvious match, but her work relationship with director and screenwriter Poul Bang was key to adapting her talents to the studio. For a few years, however, she and Bang left Saga for Nordisk Film studio. It is very probable that their common exit first and foremost was designed to create possibilities for Reenberg, who due to the skill and position of chief cinematographer at SAGA, Aage Wilstrup did not get enough breaks. At Nordisk however, Reenberg achieved a break-through to be reckoned with as cinematographer of high profile documentaries and several feature films from director couple Bjarne and Astrid Henning-Jensen: De pokkers unger (Those Damned Kids, 1947), Kristinus Bergman (Kristinus Bergman 1948) and Astrid Henning-Jensens Palle alene i verden (Palle Alone in the World, 1949). Especially in the co-operation with Astrid Henning-Jensen, Reenberg experienced how she could be a decisive creative force on equal footing with the director.

In 1949, she received – as the first cinematographer ever – an honorary Bodil film prize for the dramatic cinematography of Kristinus Bergman. Her artistic profile made her an indispensable asset for Saga, which had come close to losing its production license a few years before, and is an obvious reason, why she was put in charge of the studio’s A product, when she returned to the studio that same year.

Top director at Saga

The Danish Film industry is unique for its many early female directors; witness Grete Frische, Astrid Henning-Jensen, Bodil Ipsen and Annelise Hovmand, who are all high profile directors during the 1940s. The role model was Alice O’Fredericks, who had been a scriptwriter since the silent days and during the sound period was a driving force as a director at Palladium and later ASA. In addition, in the thirties and forties it was common practice that the role of director was shared among two, sometimes more people with different professional profiles and often with different gender. The success of Alice O’Fredericks, alone and in collaboration with Lau Lauritzen Junior, was certainly seen as a recipe for successful (and popular) film making, and Saga boss John Olsen was set on making a creative team out of Poul Bang and Annelise Reenberg, now that he had not succeeded with the pairing of Bang and Grete Frische (Hartvigson V). In practice, Bang would specialize in cheaply produced farces and comedies, while he also worked as production leader on Reenberg’s more high-grade films (Pedersen I).

Homeland Films

At ASA studios Henning Karmark had bought the rights of Mortens Korch’s homeland novels and the spectacular success of Alice O’Fredericks’ and Jon Iversen’s De røde heste (The Red Horses 1950) heralded a decade, which was dominated by homeland films. Upon her return to SAGA, it fell in the lot of Reenberg to develop a particular Saga approach to the genre. With input from Poul Bang, studio boss John Olsen, and script-writer Paul Sarauw, the studio successfully launched a Saga studio house style for the genre. Whether based on French plays or older Danish literature the stories were updated to a contemporary rural and provincial setting with a characteristically strong relationship between characters, nature and tradition. In Reenberg’s camera the fields, buildings and landscapes become narrative and thematic generators, which vibrate with energy alone and together with the films’ characters (Hartvigson III). In Fra den gamle købmandsgaard (From the Old Mercheant’s House, 1951) an unbreakable union is established between returning daughter (Astrid Villaume) and her childhood home, as she is visually tied to its rooms, barns and courtyard, as she searches for her family in an energetic and familiar fashion. In Bruden fra Dragstrup (The Bride from Dragstrup, 1955) the agency of buildings and surroundings achieve what characters cannot.

Runaway bride and heiress (Helle Virkner) has left her groom at the altar and returned to her family estate with the man she loves (John Wittig), whom she pretends to be married to in order to spare the fragile grandmother (Clara Pontoppidan). They are adamant that they will remain chaste, but when ancient buildings, the summer nightscape and singing villagers seem to inspire and bless their sexual encounter, they cannot help but consummate their love. Danish types from archaic to contemporary types give an omnipresent sense of folklore, as in the famous opening sequence of The Old Mill on Mols, where the dramatis personae and the actors, who play them are being related to us by the country mail carrier with an emphasis on the typical, the quaint and the well-known.

To a much larger degree than ASA’s homeland films, Saga homeland films draw on folklore. Whether they take place on Mols, Marstal or in King’s Copenhagen, their milieus have a mythical and imaginative quality, sometimes underlined by folklore, mythology and ghosts. In the final sequence of From the Old Mercheant’s House Reenberg creates cinema magic by deftly combining the mundane and the fantastic, religion and superstition. In the kitchen the housekeeper checks the Christmas goose, while at church the congregation sings a classic hymn, and the elves ring the bells in the tower, before finally, a sweeping camera movement sends us flying into the Christmas night.

Colour, stars and performance

SAGA’s first colour film, the giant investment Styrmand Karlsen (Ship Mate Karlsen, 1958) is a direct consequence of the competition from television, and also witnesses how Reenberg’s prestige productions to a higher degree begin to draw on farce, romantic comedy, and star performances. The growing commercial value of popular music and performers required her to create characters for stars, from teenage sensation Gitte Hænning to internationally celebrated songstress Vera Lynn. It is a testament to Reenberg’s diligence and care in all phases of production, that the stars and their performances seem genuinely involved in the dramatic action of the films. This is certainly the case in Han, hun, Dirch og Dario (He, She, Dirch and Dario, 1962), where dueling idols Hænning and Italian tenor Dario Campeotto’s rendition of ‘Den første gang jeg var forelsket’/’The first time I was in love’ is elegantly and fatefully woven into the drama by Reenberg’s moving camera. Legendary comedian, Dirch Passer, who had already had his breakthrough in Poul Bang’s 1950s’ comedies and farces, had some of his biggest successes in Reenberg’s films such as Styrmand Karlsen and The Baroness from the Gas Station. While Passer’s formidable popularity often drew on screaming and burlesque physical comedy in films such as the Poul Bang farce Charles Tante (Charles’ Aunt, 1959), Reenberg aimed at integrating Passer’s persona into his fictional characters and the fiction. In the hugely successful operetta adaptation, Mam’zelle Nitouche his double role of operetta composer Floridor and convent music teacher Celestin certainly had a potential for jest and overplay, which could well have capsized the film. However, Reenberg evenhandedly calibrates Dirch Passer’s comedy by letting Lone Hertz’ Nitouche be part of the festivities as in the delightful ”Grenadervisen”/”Ballad of the Grenadier”. In addition, Reenberg lets Passer’s wildness be echoed by the film’s style with film tricks and play with the extra-diegetic music of the musical numbers. The somewhat overlooked En ven i bolignøden (A Friend in the Housing Shortage, 1965) also illustrates Reenberg’s ability to balance different kinds of comedy. While appealing to our warmer emotions with a plot and theme about solidarity and social housing for all, the film also deals in wild absurdity via the masterfully top gear performances by Sigrid Horne-Rasmussen as housing minister and Gabriel Axel as foreign ministerial official.

Gender and Sexuality

Reenberg was at the helm of Saga’s expensive period piece Hurra for de blå husarer (Hurrah for the Blue Hussars, 1970) about love intrigues in a soldier setting anno 1893. In the context of sexual revolution, women’s liberation and youth rebellion, Hurrah for the Blue Hussars was like a red cloth for critics and intellectuals. Accordingly, it was severely castigated by Drude Dahlerup, who predicted that folkekomedier like this one soon will be a thing of the past: ”When the real world is filled with porn, the folkekomedie sex scenes are fully dressed and uncorporeal, only suggested. When reality has youth rebellion, folkekomedie has a well-behaved youth, who respect the unlimited authority of their parents (…) while the femininity of the heroines stoops to imbecility.” (Pedersen II).

Hurrah for the Blue Hussars was old-fashioned compared to other successful erotic and porn comedies form especially Palladium and Merry Film studios. Reenberg’s folkekomedier have nevertheless continued to hold power of attraction for both original and new generations of audiences. Apart from the comfort and cultural identity, such films arguably offer, they also feature an eroticism, which is often as queer as it is conservative. The disguises and double identities of the comedies give characters and plot arsenals of sexual ammunition. Just look how the title character of Mam’zelle Nitouche sexualizes herself and is sexualized by her stage experiences and musical performances. The sexualization, however, is qualified by Reenberg’s direction of Lone Hertz’ as an innocent, childish and playful Nitouche. Another striking combination of sexuality and innocence is found in Min søsters børn på Bryllupsrejse (My Sister’s Kids on Honeymoon, 1967), where the kids attend a striptease performance in a nightclub. Even though this part of the grown up experience is alien to them, they try their best to understand and relate to it, and helped by the alcoholic cocktails, they playfully and innocently inhabit the grown-up spectator role.

Annelise Reenberg came close to challenging the romantic comedy genre and the status of Ghita Nørby and Ebbe Langberg as Danish film’s top romantic couple of the sixties in the surprisingly edgy Peters baby (Peter’s Baby, 1961). With its portrayal of a man with strong paternal instincts and a woman with no contact to her maternal ones, Reenberg was not the least afraid to challenge preconceived notions about gender and roles. This was further developed in the My Sister’s Kids series, which playfully exposes mother love and the heterosexual nuclear family, while placing an alternative family on a pedestal with Axel Strøbye’s bachelor uncle as ideal parent.

Reenberg fully uses the potential of the homeland films, which celebrate landscape, tradition and the multigenerational family, to create both traditional and highly erotized universes. Here grandmothers and housekeepers are deeply involved in the romantic unions of the young, and we witness how romance emerges in the context of beautiful landscapes and family farms and traditional spaces such as the old church in From the Old Mercheant’s House. The enchantment sequence from The Bride from Dragstrup, which has been described above, subtly connects the sexual urges of a modern couple with tradition and folklore. Perhaps the most striking example of Reenberg’s queer edge is found in Kristiane af Marstal (Kristiane of Marstal 1956), where traditional marriage is charmingly exposed and deconstructed.

Kjeld Jacobsen and Louis Miehe-Renard are shipmates and best friends, whose lift together is interrupted by marriages and carreer change. They realize they miss their maritime life together and temporarily leave their wives on dry land for life on their beloved boat. The ending, which sees the shipmates sail away, while their wives and parents in law wave goodbye both celebrates conservative values of the two sailors such as industriousness and solidarity. The ending also delivers a surprisingly direct allusion to sexual excitement, as they rejoice at the prospect of sharing the cabin again, suggesting that their life at sea is characterized by a very different preference and practice than their heterosexual life on land. (Hartvigson I). A queer potential is also making itself felt in the emotional conflict between Ghita Nørby’s Anne, baroness to be and Maria Garland’s surly grandmother baroness in The Baroness from the Gas Station. It is very striking, how the build-up to the physical and emotional coming together of the two women to a high degree eclipses the heterosexual union of Anne and her Hans (Dirch Passer) (Hartvigson II).

Within academic criticism, Annelise Reenberg’s reputation is that of a gifted craftswoman, who set aside her artistic potential within drama and documentary to work with folkekomedie storytelling. However, In order to fully comprehend the inheritance from Reenberg, we must acknowledge the artistic potential of the popular genres. Reenberg’s artistic project is closely tied to her flair for investigating the norms we live by in a traditional and well-known context, and not least her ability to envision our dreams of both stability and change.

Author: Niels Henrik Hartvigson holds a ph.d. in Film and Media at the Univeristy of Copenhagen and is an a part-time lecturer at University of Copenhagen’s Saxo Institute and the Section of Film Studies and Creative Media Industries.

Literature

Bondebjerg, Ib 2005. Filmen og det moderne, filmgenrer og filmkultur i Danmark 1940-1972. Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag A/S.

Dinnesen, Niels Jørgen og Kau, Edvin 1983. Filmen i Danmark. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Hartvigson (I). Niels Henrik 2013: Rural Intentions – Sexuality in Danish Homeland Cinema, Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, årg. 3, nr. 2, p. 107-124, København: Intellect, Ltd.

Hartvigson (II). Niels Henrik 2016: Queer teori og Baronessen fra Benzintanken, Mærkk – Æstetik Og Kommunikation: Filmanalyse, p. 251-265, AAU, Aalborg: Systime.

Hartvigson (III). Niels Henrik 2021 Homeland Cinema, History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh.

Hartvigson (IV). Niels Henrik 2021 The Danish folkekomedie tradition – the art of the popular in A History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh.

Hartvigson (V). Grete Frische – The Popular Running Through Her Veins: Script-writer, Director and Comedian. Nordic Women in Film: nordicwomeninfilm.com.

Nørgaard, Erik 1971. Levende Billeder i Danmark, Copenhagen: Lademann Forlagsaktieselskab.

Pedersen (I). Paw Kåre m. Niels Jørgen Klement 2016. Historien om Saga Studio – John Olsen-tiden, Copenhagen: Mellemgaard.

Pedersen (II). Paw Kåre m. Niels Jørgen Klement 2018. Historien om Saga Studio – SAGA Film A/S, Copenhagen: Mellemgaard.