When Alice O’Fredericks made her debut as Denmark’s first female film director with Ud i den kolde sne (Out into the Cold Snow 1934), she was already an experienced actress and high-profile screenwriter for Denmark’s most popular comedy and farce director Lau Lauritzen Sr. at the Palladium Studios. Here in the early thirties O’Fredericks developed together with his son, Lau Lauritzen Jr. the modern folk comedy, whose fast-paced, fresh and singing films played an invaluable role in Danish film’s survival after audiences for domestically produced films were decimated after the transition from silent films (Dinnesen and Kau 1983: 66). Alice O’Fredericks’ status at Palladium in collaboration with Lau Lauritzen Sr. and Jr. and her convincing breakthrough were certainly decisive factors in Danish film’s unique openness to high-profile women in the film industry. In the forties alone, in addition to O’Fredericks, Astrid Henning Jensen, Bodil Ipsen and Grete Frische also worked as acclaimed directors, just as the later director, Annelise Reenberg, broke through in this decade as Denmark’s first female cinematographer. In the thirties, however, Alice O’Fredericks was the only female director, and journalists and readers took an interest in the powerful and successful woman who lived in a childless marriage with head of department Oskar Klintholm and her mother as housekeeper. Gender and femininity are often discussed in interviews and portraits, which testies to how an emerging version of female gender and femininity was perceived. There is both interest and concern about how a woman can manage herself professionally in terms of gender and emotions in collaboration with men (Pedersen 2010: 101, 109-9). Alice O’Fredericks was very aware of the insecurity regarding herself as a professional woman, and when she discussed her many films about children, families, fertility and abortion issues, she emphasized being emotional and motherly. For example, she explained how her gender proved an advantage during the week-long research at a maternity clinic during the preparation of the fertility film Vi vil ha’ et barn (We want a child 1949), and in connection with the Father of Four films she emphasizes her motherliness and pride in the child actors (Pedersen 2010: 106). By listing these films as a valve for maternal feelings and femininity, O’Fredericks lived up to contemporary gender norms, although the fact that her version of femininity and emotionality were not only spontaneous but could be activated strategically, which may also have been seen as a troubling innovation in a former media reality. It is more surprising how subsequently and up into our time, one finds suspicion of Alice O’Fredericks based on gender and body. In the only monograph about her, From Fy & Bi to Father of Four: Mrs. Alice O’Fredericks’ by La Cour and Mylius Thomsen, a series of anecdotes that focus on her gender are deemed authentic by the authors, although they are often weakly substantiated. The story of how O’Fredericks tried to buy child star Ole Neuman from his parents portrays her as a frustrated, childless woman who has completely lost touch with reality (La Cour &Thomsen 1997: 179). Descriptions of greedy and calculating sexual behaviour are widely presented, from repeated allusions to her allegedly use of sexual favours to advance her career, to anecdotes about how the mature filmmaker conducted herself in public with young men as sexual trophies (La Cour &Thomsen 1997:34, 184, 240; Pedersen 2010: 107-108). Similarly, they bring stories of Alice O’Fredericks’ abnormal physicality when, in the latter part of her career, she is described as greedily chocolate-eating and overweight, just as the image of her insisting on working despite an arthritis is presented as grotesque (La Cour &Thomsen 1997: 213-214). Even academics, like Carl Nørrested stoops to hint at sexual favours. He sarcastically comments on her acting debut in Häxen (Witchcraft Through the Ages 1922), where her character kisses the backside of the devil, played by director, Benjamin Christensen: “It was never before or since allotted anyone to make their debut kissing the country’s leading director in the backside” (Nørrested 1996: 24). While such frequent attacks on her person are obviously connected to her gender, they should no doubt also be understood in the context of the cultural aversion to her films from academics and cultural leftist journalists (Dam 2017).

A Professional Naivist

Early in her career, Alice O’Fredericks developed an ability to combine analysis and overview in all phases of film production with a naïve and folksy outlook. Because of this, her work has been disrespected, and the genre of popular comedy which she continually honed has repeatedly been disparaged and disallowed by dominant institutions such as the National Film School of Denmark (Dam 2017). Throughout O’Fredericks’ directorial career, and especially from the forties onwards, there have been repeated accusations, especially from the capital’s press and academics, that cold calculation lurks behind her films’ naïve charm and cosy folklore. Based on the notion that intuitive genuine folklore is incompatible with professionalism, Bent Pedersen in his review of Mosekongen (The Marsh King 1950) casts suspicion on her ethics: “In Alice O’ Fredericks’ film directing, not a second of willingness to give more is felt than precisely that which is not good; One would settle for a hint of desire for folk comedy as comedy and not as speculation. Just a hint. Well, no luck here.” (La Cour &Thomsen 1997: 159). In a 1936 interview in Nationaltidende, in which she rebukes the criticism of her and Lau Lauritzen Jr.s folk comedies, the journalist describes her as a temperamental and twisted upper-class lady – and a poor advocate of popular entertainment: “Her hands with the giant rings grope unhappily at the shiny things on the Christmas tree, Connie’s Christmas tree, while she stares out the window of the old Hellerup villa” (Pedersen 2010: 110). Other sections of the press were more appreciative of O’Fredericks’ popular approach. The popular newspaper, BT’s birthday portrait from 1950 highlights her unique ability to combine the heartfelt and the professional: “To know Alice, you must also have met her during work. And you haven’t stood in the background in the studio for many minutes before you realise how well-respected she is. She knows her stuff, she knows the film technique inside out, she has amazing insight into people and their reactions. She knows how a genuine smile can light up the actor’s face and how his shoulders should sag when he is grieving” (Pedersen 2010: 113). The same point is made by Poul Reichhardt, who acted in her films throughout his career. In an interview in Århus Stiftstidende in 1971, he defends Alice O’Fredericks’ Vagabonderne på Bakkegården (The Vagabonds at Hill Farm 1958), which is portrayed by the journalist as less genuine in its folklore than Erik Balling’s Huset på Christianshavn (The House on Christianshavn 1970-77): “I am not so sure that it is not the same popular vein. It just happened that ten or twenty years ago, when folk comedies of that time were being filmed, people preferred to see the rural environment portrayed, now we moved to the city. In both places, the audience rejects comedy which is not genuinely felt by both the director and the actors. We have plenty of examples of constructed folk comedies having fallen to the ground. Some of the most heartfelt Danish folk comedies, I believe, died with Alice O’Fredericks, who from the bottom of her heart was a professional naivist” (Pedersen 2010: 116). This interpretation is supported by the Little-Per actor, Ole Neumann, who also experienced the naïve and cosy nature of her films as being heartfelt (La Cour & Thomsen 1997: 219). Tina Mariager, who plays the parson’s youngest daughter in O’Fredericks Næsbygaard trilogy (1964-66) and is one of O’Frederick’s last child stars, describes how the familiarity and cosiness of the films was a product of a warm and familiar production planning (Tina Mariager 2024).

Training – Benjamin Christensen, Lau Lauritzen Sr.

Alice O’Fredericks was hired as secretary to Benjamin Christensen at Nordisk Film Company in 1918 and quickly took on the role of script-girl, as well acting in smaller parts. Unlike the office job at Employers’ Accident Insurance where she came from, Alice O’Fredericks thrived in the film world, which offered an opportunity to jump between job functions, and she referred to her time with Christensen as an invaluable master lesson in all aspects of film. Benjamin Christensen had established himself as a high-profile filmmaker who wrote, directed and starred in his melodramas. Not least, he staged himself as an artist and created the prototype of an auteur at a time when film was a 100 percent commercial enterprise. Under Christensen, Alice O’Fredericks worked on a project about ghosts, which was never finished (Pedersen 2010: 35). Witchcraft Through the Ages, on the other hand, with its experimental mix of horror, scientific treatise and problem film, became a scandal success, which to this day is recognised as a classic in the horror genre. In addition to her work as a script-girl, Alice O’Fredericks plays several roles as obsessed women in the film. When, based on the success of Witchcraft Through the Ages, Benjamin Christensen travelled to Hollywood, where he directed a number of horror films, O’Frederick was employed as an actress at Palladium Studios, where she played a major role in the nature drama, Hadda Padda (Hadda Padda 1923).

Together with actor and director Johannes Meyer, she also set up her own film company, Tumlingfilm (Toddler Films), which produced about four films (Pedersen 2010: 36). However, when O’Fredericks won a script competition in 1927, she accepted a job offer from Palladium Studios, where she served as regular screenwriter, gag-man, sparring partner, assistant director and editor under director, Lau Lauritzen Sr. The unpredictable and experimental development processes of Benjamin Christensen and Toddler Films’ limited success were diametrically opposed to Lau Lauritzen Sr.’s successful comedy couple formula of Fyrtårnet & Bivognen (The Lighthouse & the Sidecar) or Fy & Bi. With an average of four films a year throughout the twenties, their comedies were Danish film’s biggest international success of this decade. From his debut as an actor and screenwriter in 1911, Lau Lauritzen Sr. was one of the most used actors in Danish film, as well as being a director and screenwriter. Between 1917 and 1920 alone, he was behind about one hundred farces and comedies and is by far the most prolific silent film director in Danish film (Pedersen 2010: 21). The long-film format broke through in 1910 within the melodrama genre, but for comedies it was Lau Lauritzen Sr. who was one of the first in the world to develop a long-film format in the early twenties. It centred around the vagabond pair, The Lighthouse & the Sidecar that first appeared together in Tyvepak (Thieves 1921). The Fy & Bi films combined farce gags and slapstick comedy with folk comedy’s touching portrayal of the two outsiders played by Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen (Pedersen 2010: 27). With touching simplicity, the two resolve conflicts and problems. However, their idiosyncratic mannerisms prevent them from being integrated into society, and time and time again we witness how at the end of the film the two walk away hand in hand towards their next adventure. The touching aspect is also expressed through the staging of the domestic Danish nature, as Svend Nielsen notes in 1951: “The success had many reasons. Lau Lauritzen was an excellent director. He loved nature, and never have the sea, the beach, the forest and the sun in Denmark been as lovely as in his films” (Pedersen 2010: 28). Lau Lauritzen Sr. recounts in an interview in the newspaper Berlingske in 1921: “I find that no matter how excellent a director or decorator, he cannot match nature itself, and the films I have the honour of sending out into the world should be completely influenced by the smiling Danish nature, which like no other in the world is suitable for the happy, sunshine-filled play” (Pedersen 2010: 29).

With her competition-winning screenplay, which would become Filmens Helte (Heroes of the Movies 1928) and subsequently in Højt på en kvist (High on a Twig 1929), Hr. Tell og søn (Wilhelm Tell and Son 1930) Pas på pigerne (Beware of the Girls 1930), Med Krudt and Knald (Long and Short invent the Gunpowder 1931), Alice O’Fredericks managed to align her scripts with Lau Lauritzen Sr.’s vision. Later on, the combination of the humorous, the touching and Danish nature also would become a benchmark for Alice O’Fredericks, and she was very aware of this legacy and repeatedly recognized Lau Lauritzen Sr. as a role model (Pedersen 2012: 137). When Lau Lauritzen Sr.’s son, Lau Lauritzen Jr. returned from his film work and educational trips in England, Germany, France and Belgium, Alice O’Fredericks was assigned as his working partner. This was the beginning of a legendary partnership that would successfully renew folk comedy and make the directors a powerhouse in Danish film.

Their way of sparring with and drawing on each other became the picture of successful filmmaking, and in the following decades it was quite normal for films to be directed by two or more directors (Hartvigson 2022a; Hartvigson 2022b). From the forties, Alice and Lau also formed working relationships with others, and Alice O’Fredericks entered into a number of creative collaborations with among others Morten Korch, Lis Byrdal, Grete Frische, Alice Guldbrandsen, Jon Iversen, and Ib Mossin.

Sound film: The classic and modern folk comedy

The transition to sound films caused major technological changes in film production. Alice O’Fredericks’ all-round experience and Lau Lauritzen Jr.’s technical experience from studios around Europe were crucial to Palladium’s folk comedies’ successful transformation from silent to talking and singing films such as the Fy & Bi films Han, hun og Hamlet (He, She and Hamlet 1932) and Med fuld musik (With Pipes and Drums 1933). Sound made Danish film an almost exclusively national affair, and Fy & Bi actors Schenstrøm and Madsen sought larger language areas to satisfy their international fan base (Pedersen 2010: 61). For a Danish audience, the sound allowed for a more culturally specific storytelling, which Alice and Lau took full advantage of as screenwriters for the audience triumph Barken Margrethe af Danmark (The Bark Margrethe of Denmark 1934) directed by Lau Lauritzen Sr. The film effectively contrasts the fishermen’s houses, dialects and sociolects in Dragør with upper-class life and -lingo in Klampenborg. The old amusement park of Dyrehaven becomes the sanctuary where the classes can meet under the leadership of a well-singing Lau Jr., who shines as a new and very physical movie star. Based on the classic folk comedy of the same name, the brave sailors of the bark are celebrated, shaking up a snobbish and scheming bourgeoisie led by Maria Garland and Arne-Ole David’s villainous characters.

In keeping with the spirit of the folk comedy tradition, it is the lowest in society whether sailors, vagabonds, illegitimate children or simple-minded people who hold the key to the creation or recreation of new social and familiar order (La Cour &Thomsen 1997: 240). The archetype example of this sentimental myth is found in the O’Fredericks and Lau Jr. scripted Københavnere (Copenhageners 1933). In the final scene, when Olga Svendsen’s cook has resolved the class and love conflict between her own illegitimate daughter and the director’s son, she stands in Tivoli surrounded by Copenhageners of all kinds. Her final song ‘København, København’ (‘Copenhagen, Copenhagen’), in which she opens her arms to an embrace, was filmed as proscenium shot, so that her desire to embrace the whole of Copenhagen seems to apply to audiences in cinemas (Hartvigson 2004: 87; Hartvigson 2021b: 69

Alice O’Fredericks was responsible for the fact that the myth of inclusion and unity came to dominate Danish film for decades to come, just as she was responsible for touching morals that, in line with the Christian penchant for victims and outcasts, confirm that we all belong. After having rewatched Copenhageners decades after its premiere, journalist and reviewer Jens Kistrup, very insightfully describes how films like this had a surprisingly large impact on an inclusive and specifically historical social mindedness: “Whether the image of society in “Copenhageners” fits – the social levelling that makes revolution superfluous – I cannot say. But I think so. And now I know where that faith comes from. In my childhood, we learned that the problems of a society could be solved – not all at once, but little by little by using one’s wits and having one’s heart in the right place. That was the indoctrination of that time – at school, at home, in the movie theatre” (Kistrup: 1977). This statement also testifies to role of cinema as a potent institution on par with family and school.

Lau Lauritzen, Sr. had so much faith in Alice O’Fredericks and young Lau that they were allowed to write and direct their directorial debut Out into the Cold Snow without interference from him. The film is in every way an energy bomb of narrative joy with shouting and screaming, reckless driving, movie tricks and hypnotist villains abducting rich widows in the Norwegian mountains. Not least, Ib Schønberg’s stardom as an antihero was thoroughly established with the slogan “Uhyggen spreder sig”/“The creepiness is spreading!” and the hit song ‘Så længe der er noget man kan ønske sig’/‘As long as there is something you can wish for’. The audience loved the film, and critics welcomed Alice and Lau’s dynamic film style and modern sensibility (Pedersen 2010: 93-94). However, the success meant that Lau Lauritzen Sr. lost his trusted assistants and ended his career with a couple of films that to some extent lack the freshness of The Bark Margrethe of Denmark and Copenhageners (Pedersen 2010: 97). Alice and young Lau’s next film Kidnapped (Kidnapped 1935) cements the modern folk comedy. From the title’s reference to the exotic kidnapping phenomenon to American gangsters, millionaires and, not least, a dynamic film style, Kidnapped channels modernity in every way. However, the fascination with everything modern and American is effectively mixed with the character types and themes from the Danish folk comedy tradition. Moreover, Kidnapped takes full advantage of the comedy genre’s opportunities to splice aesthetically and epistemologically disparate elements (Hartvigson 2005: 65). This is especially true in the riveting and absurd action sequence, where the film’s allotment garden house, which if anything symbolises Danish hygge (cosiness) and its residents, end up as targets for rockets and artillery during a military exercise.

New stars, children and childishness

In Kidnapped, Arthur Jensen and Ib Schønberg’s Lasse and Basse appear here for the first time as a comic male couple after the Fy & Bi model. In addition to physical comedy, the two also lead the way in all forms of voice, speech and idiosyncratic language play from slang to catchphrases (Hartvigson 2007: 33ff, Hartvigson 2021b: 67-68).

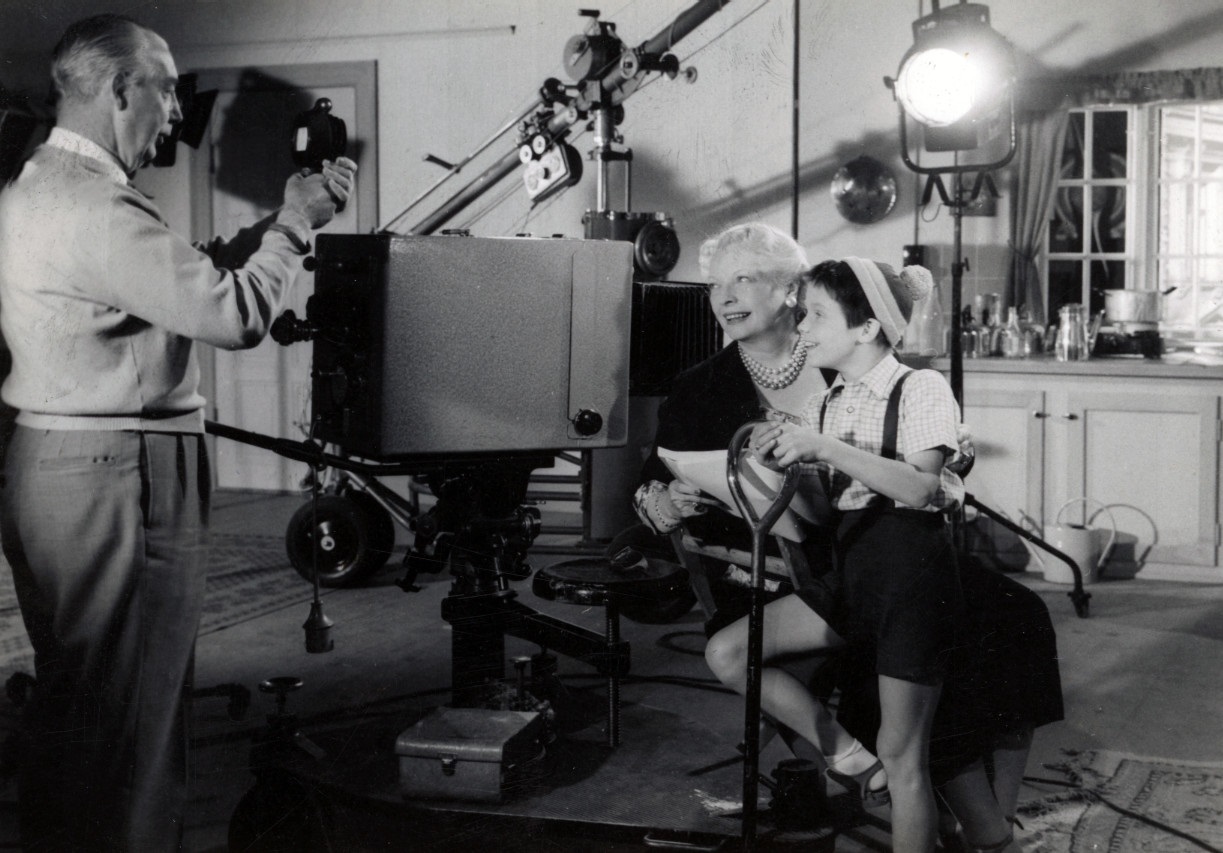

For Kidnapped O’Fredericks and Lau Jr. launched child star, Little Connie, who proved a veritable coup. Apart from charming an adult audience, her drawing power effectively expanded the folk comedy audience to include the very young. Alice O’Fredericks was the prime mover in Palladium’s search for a Danish Shirley Temple, who had effectively demonstrated how the impact of the child character was maximised through sound films (Hartvigson 2007: 38-39). The directors had seen one of Temple’s films in Stockholm, and O’Fredericks’ intuition was on the money, when she signed a contract with the parents of three-year-old Connie Meiling (later Link), who could sing, dance, memorise and deliver lines (Pedersen 2010: 125). Threatened by kidnappers, abandoned or neglected, Connie is largely responsible for the touching dimension of the films. At the same time, she unproblematically takes part in the comic universes, as she inspires adults to unity and play with her childish charm and immediacy. Whether it is morning gymnastics, crime fighting or singing together, the unmanly male couple of Lasse & Basse and Connie turn out to be the best educators, protectors and playmates for each other. Kidnapped cements the alternative outsider family as an unequivocally positive trope, pointing forward to the fifties’ homeland movies and the Father of Four series. The Lasse & Basse and Connie constellation continued successfully in The Snoopers, which turned up the baroque antics and the run-away success, Panserbasse (Copper 1936), which took Ib Schønberg’s popularity to new heights in a film about gangsters from Mexico in hot pursuit of the drawings for the silent machine gun. These exotic plot elements are put into a folk comedy perspective by young love, a child-friendly local cop Basse and his unmanly partner Lasse. A new feature among the everyday Danish types is an unjustly convicted unemployed man (Poul Reichhardt) who, in desperation tries to take his life before being rehabilitated with work, becoming engaged and displaying heroic behaviour.

ASA and the revue’s big stars

Together with Henning Karmark and John Olsen, Lau Lauritzen Jr. founded ASA in 1936, where he and Alice O’Fredericks continued their collaboration. Actors Schønberg, Jensen and Connie, who were still contractually attached to Palladium, did not move to ASA until later. In the meanwhile, the directors’ first priority was to establish Osvald Helmuth as a movie star of folk comedies (Pedersen 2010: 197). After actor Frederik Jensen’s death, Helmuth had established himself as Denmark’s greatest male popular revue artist, and his persona as worker and common man was already legendary for their emotional intensity and their faulty but ingenious language choices. O’Fredericks and Lau Jr. systematically staged Helmuth’s over-the-top playing style to replicate the direct contact strategy between star and theater audience from popular revue, which is a very manifest example of comedy’s interaction between audience and fiction (Kruuse 1964: 136-7, 196; Hartvigson 2023a: 70). This is particularly evident in the musical numbers’ performative character staging, which invites the cinema audience to an assimilated direct participation and, in the best revue style, to respond to the fiction (Hartvigson 2007: 73-74; Hartvigson 2021b: 69, Thomsen 1986: 231, 248). In En fuldendt gentleman (A Consummate Gentleman 1938), Helmuth butcher performs for his enthusiastic customers, which underlines both his fictional character and his extra-fictional star status (Hartvigson 2007: 163). Critics perceived this strategy as primitive and a dead end in cinematic terms. However, in the reviews, which were written on the basis of opening night screenings, the reviewers again and again disgruntledly testify to audiences singing along, interacting with the characters and commenting loudly on the plot (Hartvigson 2023a: 70). In Der var en gang en vicevært (Once Upon a Caretaker 1937) co-directed with Lau Lauritzen Jr., Helmuth plays the kind-hearted caretaker with Little Connie as foster daughter. The two childish souls mirror each other in a touching interaction from their cheerful waking-up song ‘God-morgen, god-morgen’/Good morning, good morning’ to the melancholy ending where the child comforts her lovesick foster father. Between the two scenes, Helmuth’s caretaker manages to save the artist collective in his building by funding a tour for them.

The film illustrates well how folk comedy uses music numbers and performances as a platform for the actor to transcend his nominal character and contact audiences across the screen. In musical numbers, from Lulu Ziegler, who sings about the threat of war in Europe, to a well-stepping Connie, who flouts the real-life rules of child performance, also mark an intertextual reference to the same artists’ star personas outside of the fiction and establish a dual relationship with the audience. The performances are also key to conflict resolution and integration, such as when the choleric director (Sigurd Langberg), who wants to shut down the tour, experiences such a success on stage as his angry self that he decides to become part of the show instead of closing it (Hartvigson 2021b: 69). The antagonist’s transformation via performance represents a regular deconstruction of the fiction, which requires the audience to renegotiate their relationship to characters and the fiction with laughter and comments (Thomsen 1986: 231, 248, Hartvigson 2023a: 69). Frk. Møllers jubilæum (Miss Møller’s Jubilee 1937) co-directed with Lau Lauritzen Jr. is a vehicle for revue star Liva Weel with both touching and exuberant music numbers that reflect the characteristic sides of her star persona. This film also marks the big breakthrough for composer/singer/actress Karen Jønsson, who plays an orphan and stands for the film’s touching dimension. Miss Møller’s Jubilee also launches the career of Børge Rosenbaum (later Victor Borge), who delivers a manic version of the great farce actor of the 1930s, Christian Arhoff. Weel and Rosenbaum’s mannered acting clearly testify to how O’Frederics and Lau Jr.’s folk comedies cultivate extreme farce and stylized types as an integral part of the contact strategy with the audience (Hartvigson 2007: 164ff). According to Børge Rosenbaum, nicknamed Bom, the primary instruction he received from Alice O’Fredericks was: “Big eyes, little mouth, Bom” (Pedersen 2010: 211).

The star films cemented the directorial couple’s ability to attract audiences, and for stars and up-and-coming actors, starring in an O’Fredericks and Lauritzen Jr. film was a bulletproof career investment. However, the Copenhagen critics in particular became increasingly critical of the films’ spiritual level (Pedersen 2010: 217). O’Fredericks and Lau Jr.’s huge output included several Swedish versions of their films from A Consummate Gentleman, which was adapted as Svensson Ordnar allt (Svensson arranges everything 1938) and onwards, which may have influenced negatively the assessment of their films (Nordin 1985: 26). O’Fredericks herself directed the Swedish versions of Miss Møller’s Jubilee, Blaavand melder storm (Blaavand Forecasts Storm 1938) og Hans onsdagsveninde (1943), respectively Julia Jubilerar (Julia Jubilees 1938), Västkustens hjältar (Heroes of the Westcoast 1940) and Onsdagsväninnan (His Wednesday Girlfriend 1946).

In the forties, O’Fredericks and Lau Jr.’s comedies gravitated towards American screwball and romantic comedy with new music stars such as Gerda and Ulrik Neumann and Marguerite Viby. When Viby joined ASA, she was already an established revue and film star with huge successes on the revue scenes of the thirties and in a number Nordisk Film productions directed by Emanuel Gregers (Hartvigson 2023: 162). She was celebrated by audiences and critics alike as the consummate Danish star with a talent for international trends of scat-singing and tap-dancing (Nørrested 1996: 29). Collaborating with Viby at ASA was an opportunity for Alice O’Fredericks to put gender and identity on the agenda. The two had already worked together on Palladium films from 1929 to 1932 such as He, She and Hamlet, where the foundation was laid for Viby’s tomboyish star persona, which challenged and experimented with gender, role and appearance. At ASA, Alice O’Fredericks directed Viby in a series of successful and relatively well-reviewed films inspired by screwball and romantic comedy as Frk. Vildkat (Miss Wildcat 1942) and Teatertosset (Theater Crazy 1944), which drew on Viby’s peppy and queer gender identity and cemented her huge popularity.

A socially responsible film culture

The late thirties herald fundamental changes in film culture. Both from political and critical hold and from within the film industry there was a drive to put the popular impact of the film medium at the service of society. This social orientation towards enlightenment, civic-mindedness and education is clearly felt in Alice O’Fredericks and Lau Lauritzen Jr.’s output. With its documentary montage of Esbjerg’s fishing industry, the fishing melodrama Blaavand Forecasts Storm links documentary information and a very tangible reality to its dramatic story. Prime Minister Thorvald Stauning even agreed to introduce the film in a prologue, where he praises it for its relevance and civic spirit, saying, among other things, “I hope that many will see this beautiful film, and I think it will raise the reputation of the fishing population and be of honour to Danish production and enterprise”. Also, in Familien Olsen (The Olsen Family 1940), which thematizes justice and the individual’s social responsibility, the civic mindedness is explicit. Symptomatic of the seriousness of these films is that in both films Osvalds Helmuth appears as a character actor and without actual song numbers. Although well-reviewed, the Olsen Family would be Helmuth’s last film for ASA in a long time, which, according to him, was because ASA preferred Ib Schønberg, who had joined the studio after finishing his contract at Palladium (Pedersen 2010: 380).

In her last film for Nordisk Film, Sørensen and Rasmussen (Sørensen and Rasmussen 1940) directed by Emauel Gregers, Marguerite Viby had scored a great success opposite royal theatre actress Bodil Ipsen, and this is probably the direct inspiration for ASA’s daring pairing of the popular Viby with another royal actor, Poul Reumert in the romantic comedy Frøken Kirkemus (Miss Church Mouse 1941). Although his performance hasn’t aged well and comes across as rather hammy, the critical reception at the time was extremely congratulatory of how Lau Jr. and Alice O’Fredericks had secured a popular outlet for this superstar from legitimate theatre and placed the film audience in the vicinity of a high culture (Pedersen 2010: 415)

The social problem film

The social problem film, which emerged as a mixture of realism and drama, was the biggest genre-oriented innovation brought about by society-oriented film culture. This genre prioritised sober and nuanced representations of societal issues and was developed in collaboration with doctors, educators and sociologists, and often focused on the responsibility of society and public institutions. The problem films relied on a new non-commercial economic logic with prizes and exemption of amusement tax, and they generally did not have the same earning potential as folk comedies (Pedersen 2021: 112-3). For Alice O’Fredericks, who was a committed Social Democrat, the social problem film and the film culture, which was developing, provided a welcome opportunity to tackle real-life problems. Her debut as solo director was with the problem film Det brændende spørgsmål (The Burning Question 1943) based on the controversial novel ‘Storken’/’The Stork’ by Thit Jensen, which deals with seduction and abortion issues. The film, which stars Poul Reumert in the controversial role of the abortion advocate, draws heavily on his gravitas and cultural status. Also, in the morality drama Affæren Birte (The Case Birte 1945) about sexual abuse of children and vigilante violence and murder, Reumert’s character as the righteous avenger is made the center of highly charged moral conflicts.

The film’s explicit treatment of sexual abuse of children was groundbreaking, as was the film’s vigilante theme that made it hotly debated in the media, and it became a huge financial success for ASA (Kau and Dinnesen 1983: 265; Pedersen 2012: 532). Problem films from Alice O’Fredericks’ hand include Elly Petersen (Elly Petersen 1944) about seduction problems and the dangerous metropolis, Det gælder os alle (It Concerns Us All 1949) about war refugees and the tuberculosis film, I gabestokken (In the Pillory 1950).

On several occasions O’Fredericks related her pride in her problem films and her hope that they would be the films for which she would be remembered (Pedersen 2012: 126).

Vulnerable and traumatised children

The representation of children in the thirties had been dominated by Alice O’Fredericks and Lau Lauritzen Jr.’s folk comedies with Little Connie. In role after role, she had played orphans and socially vulnerable children in dangerous situations, which had, however, always been averted, and where her childlike outlook had ensured her and her adult friends an unequivocally bright fate. In Pas på svinget i Solby (Beware of the Bend in Solby 1940) by O’Fredericks and Lau Lauritzen Jr., Connie, in this her last film, plays poor little Anna, who loses her mother. Although the film is a folk comedy and ends well for everyone, it gives a much more down-played child portrait without the child star’s characteristic exuberance and music numbers, and the quaint suffering of little Anna points to the socially and psychologically vulnerable and traumatised children who occupy such a prominent position in film culture in the forties. With accusations directed at absent parents and society, director Svend Methling’s problem film Det Store Ansvar (The Great Responsibility 1944) was the first to really introduce a Danish audience to the dangers, which threatened socially vulnerable children and young people. Shortly hereafter, Alice O’Frederick’s and Lau Lauritzen’s Jr.’s The Case Birte, with Verna Olsen in the title role as the victim of a sexual assault, gave an uncompromisingly direct description of the child trauma. After Birte has been saved from her aggressor, the doctor tells her parents, that while she will probably not suffer any physical trauma, a complete recovery is doubtful, as she may not avoid mental suffering. Alice O’Fredericks continued this line of critical filmmaking to stress a common responsibility to learn from and help vulnerable children with It Concerns Us All. Both the performances of Ilselil Larsen as Austrian child refugee and Tom Rindom as a physically handicapped boy remain thought-provoking examples of children’s insurmountable mental and physical traumas.

New women and new family norms

Diskret ophold (Discreet Stay 1946) by Ole Palsbo had created a touching defence manifesto for unmarried women who gave birth in secret, and a year later Soldaten og Jenny (The Soldier and Jenny 1947) had pleaded charity for women, who had had illegal abortions. The same liberated attitude characterises Alice O’Fredericks and Lau Lauritzen Jr.’s We Want a Child. The film, which deals with parenthood and pregnancy problems, also pleads for families’ right to have children, even if they have had an illegal abortion earlier. And as something completely new, the film introduces the state-supported one-parent family. The film follows the young couple Else and her boyfriend (Ruth Brejnholm and Jørgen Reenberg), who cannot conceive. She had an abortion during the war, when he had to flee to Sweden, and this has reduced her chances of conceiving. Her friend Jytte (Grete Thordal), on the other hand, who is in a relationship with a married man, becomes pregnant. Through her doctor, Jytte tries to get in touch with someone who can perform an abortion. Instead, he puts her in touch with Mødrehjælpen (The Mother Help), who can assess her situation and help her. Jytte decides to give birth and later, with the help of Mødrehjælpen, decides to keep the child as a single mother. With nurture, maternal instincts and responsibility, this unmarried mother is presented as a role model for the audience as well as for the married Else, who ends up becoming pregnant herself. The film unequivocally legitimises the state-supported single-parent family unit, just as it does not condemn motherhood achieved through active and pleasure-driven sexuality. The film’s exceptional free-mindedness was also expressed in its explicit portrayal of the ultra-modern controlled and efficient birth, scientifically controlled by doctors and nurses. We Want a Child struck a magical balance between the tastes of critics and audiences and was a massive financial success for ASA (Pedersen 2012: 120). The film was awarded at international film festivals and sold for distribution abroad and is an early example of how Danish free-mindedness achieved international impact (Thorsen 2021: 142; Pedersen 2012: 117ff). On the basis of the film’s social intention, Alice O’Fredericks had succeeded in obtaining tax exemption from the Minister of Finance, H.C. Hansen, even though it was normally only given to finished films. However, the tax exemption was granted on condition that the cultural ethos was augmented, and that popular Grete Frische’s manuscript would be prepared by Leck Fischer under the supervision of doctor Ib Freuchen (Pedersen 2012: 111, Hartvigson 2022b).

This is the first of three Alice O’Fredericks films where Grethe Thordahl plays sexually knowing unmarried women. In Fodboldpræsten (The Soccer Priest 1951), her character’s desire to be with her theologian fiancée (Jørgen Reenberg) is portrayed as natural and life-sustaining. In The Smallholder’s Girl, Thordahl plays the sexually stigmatised heroine whose psychological and social emancipation commences, when she stands by her illegitimate child. O’Fredericks’ positive representation of pleasure driven female sexuality even when it is procreative is a strikingly progressive affirmation of female sexual identity.

In the late forties O’Fredericks had investigated the human experience with women at the centre in Så mødes vi hos Tove (Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s 1946) Hr. Petit (Mr. Petit 1948). These two films, discussed below, are conspicuously ambiguous in terms of moral and remain outstanding examples of O’Fredericks’ analytical sharpness and her willingness to experiment with narrative and theme.

New collaborations and narrative and thematic experiments

In 1950 Alice O’Fredericks and Lau Lauritzen Jr. co-directed their last film together, the large-scale but relatively unsuccessful comedy Den opvakte jomfru (The Awakened Virgin 1950) by the cultural radical Poul Henningsen and starring Ib Schønberg and Marguerite Viby. Already from the beginning of the forties, the demand for Danish films during and after the occupation had meant that the experienced couple started directing alone or pairing up with other less experienced filmmakers. Lau Lauritzen Jr. had from the early forties cultivated a film directing collaboration with theatre legend Bodil Ipsen, and their films together were huge critical successes, which were seen as heralding a long-awaited maturity for Danish films. Ipsen and Lauritzen Jr.’s realistic war drama De røde Enge (The Red Meadows 1945) achieved legend status in its own time, and their Støt staar den danske sømand (Stoutly Stands the Danish Sailor 1948) and Café Paradis (Café Paradise 1950) both received the newly created critics’ prize, The Bodil for best film of the year, which was also to go to Lau Jr.’s solo projects Det sande ansigt (The True Face 1951) and Farlig ungdom (Dangerous Youth 1953).

In the same period Alice O’Fredericks headed a record number of productions and depended on collaborators to assist and under-pin the O’Fredericks brand. These included co-director, Jon Iversen, screenwriter and writer Alice Guldbrandsen and screenwriter and idea man, Grete Frische. After a short career as a director at the newly created SAGA Grete Frische had resigned and joined ASA, where she served as screenwriter, sparring partner and right-hand man for Alice O’Fredericks. Frische’s ability to endow folk comedy situations and characters with a realistic weight was of great importance to the Alice O’Fredericks brand during this period (Hartvigson 2022b). In her first assignment at ASA as screenwriter for the Alice and Lau directed Jeg elsker en anden (I Love Another 1946), Grete Frische used the contemporary lack of childcare as a backdrop for the romantic intrigue between Marguerite Viby and Ebbe Rode. Together with Alice O’Fredericks, Frische was screenwriter and co-director of Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s, about eight female schoolmates who meet and exchange life stories. One of them is film director Lis played by Gudrun Ringheim, who, with her pragmatic approach to film production, sense of audience demands and natural authority both function as ironic commentary on the tastes of audiences and critics and is clearly intended as a self-portrait of Alice O’Fredericks.

The film is also a good example of Grete Frische’s type- and situation-driven folk comedy, and she herself plays the lisping maid Norma, who puts her employers in place (Hartvigson 2022b). Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s combines types and situations in quite an idiosyncratic way; The film spans operetta intrigue, social-realistic reportage, slapstick-comedy and melodrama, as it delves into the secrets of its characters be they fatal deception or a penchant for whipped cream cakes. Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s’ imaginative mood shift and genre-diverse characters pull in vastly different directions and make the film thematically challenging and without any traditional unifying and human moral centre (Hartvigson 2022b). In the film’s final plot twist, Gerd (Gull-Maj Norin), who after humiliations and loss has fought her way back to life, turns out to be the victim of yet another cruel deception.

The film was not a financial success and received a somewhat mixed reception. Instead of seeing a potential in the impressive genre range, critics were busy assessing it negatively compared to Johan Jacobsen’s drama Otte Akkorder (Eight Chords 1944), which was judged to be more stylish and dramatically effective. Referring to Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s’ random game of fate, Svend Kragh-Jacobsen in the Berlingske review went so far as to label it “the unpleasant film” (Pedersen 2012, p. 37). The sharp, unpleasant, moral-less, coincidental edge is an excellent example of the critical-analytical view of the connection between sexual drive, identity and isolation that had started to make itself evident in the forties films (Hartvigson 2013b). In various contexts, the film is described as a women’s film (Pedersen 2012: 28), which fits in the sense that it is a film by and with women. However, the film far from displays any progressive message of feminine strength or female solidarity. The same may be said for Mr. Petit, which fascinatingly continues the narrative and morally experimental line and could not be further from the popular and sun-drenched films for which O’Fredericks is associated with today. It was made in collaboration with Alice Guldbrandsen, author of the novel about the seducer and murderer of women, Jean Petit. Mr. Petit is a devastating film that offers a full-blown deconstruction of all kinds of romantic notions of love and solidarity, just as it to a large degree renounces being an edifying movie experience. The film follows a changing cast of women, waiting to be destroyed with a surprisingly low level of sympathy, as it seems more concerned with understanding the psychological and cultural dynamics that isolate and victimise the women. Mr. Petit renounces both main characters and a continuous identification, which lend to its icy and sharp tone.

The tone is set from the first scene, which presents the audience to a voltage field of contradictory feelings in the enamoured and giddily expectant Madame Picot, her jealous and rude son, the acid governess, the insolent maid and the discrete murderer, who floats like a spirit through the house (Betty Söderberg, Jon Brammer, Jessie Rindom, Lily Broberg, and Sigfred Johansen, in that order). Mr. Petit’s combination of the spectacular with analytical distance O’Fredericks bears some thematic resemblance to her mentor, Benjamin Christensen’s masterpiece, Witchcraft Through the Ages. Simultaneously, it points forward to narratively and thematically experimental true crime-series such as American Crime Story: The Murder of Gianni Versace (2018).

Alice O’Fredericks had hoped for a tax exemption film for quality, but in vain, and Mr. Petit became the hitherto biggest economical fiasco in ASA’s history (Pedersen 2012: 103). Also, critics had trouble understanding the film’s quality and Mr. Petit heralded an unequivocal goodbye to narrative and thematic experimental film.

ASA’s balance between popular and high culture

The distinction between high and low culture became firmly cemented in the fifties, and Alice O’Fredericks’ popular profile became the touchstone for what was not art, which had already been visible in the critical receptions of Mr. Petit and Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s. The critics’ habitus in dividing into art and rubbish was to all accounts not of importance to the large audience, but had an influence on the intelligentsia, politicians and thereby on legislation and various institutional practices (Dinnesen og Kau: 259). In order for ASA to retain the premiere cinema, Kinopalæet in Copenhagen, it was stipulated that three to four films a year had to be produced by the production company (Pedersen 2012: 365). Alice O’Fredericks’ annual Morten Korch adaptation, other homeland films and Father of Four films represented two to three films a year and the lion’s share of ASA’s earnings. However, it was also stipulated the studio’s production had to live up to a level of quality, which spelled realism, topicality, which was the studios yearly critics-friendly production such as Lau Jr.s The True Face and Dangerous Youth was important (Pedersen 2012: 331). Many influential critics were suspicious of both the commercial and the popular, and it seems that ASA and O’Fredericks made a strategic decision not to associate O’Fredericks’ name with the studio’s critical and prestige productions, just as Lau Lauritzen Jr. would no longer be associated with folk comedies. Alice O’Fredericks herself told Politiken in 1958 about the collaboration at ASA: “We have divided the roles in so that he is the one who makes the films that gets the Bodil prize'” (Pedersen 2012: 157). However, there is ample evidence that the former directing partners continued to be involved in each other’s projects (Pedersen 2010: 584; Pedersen 2012: 382). In Pedersen’s words, Alice O’Fredericks was involved in everything that took place at ASA, working on auditions and scriptwriting for a large number of Lau Lauritzen Jr.’s productions (Pedersen 2012: 407). She was thus involved in Stoutly Stands the Danish Sailor (Pedersen 2010: 584), as well as writing the script for the Bodil-winning Bundfald (Residue 1957) although it is credited to director Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt (Pedersen 2012: 382). Similarly, Lau Jr. worked as a photographer on O’Fredericks De røde heste (The Red Horses 1950) without being credited (Pedersen 2012: 129).

In a portrait article about O’Fredericks from 1996 Carl Nørrested writes: “From the 50s, Alice O’Fredericks lost her committed sense of the contemporary. Frantically, she tried to keep herself informed and demonstrate that she was still up to date” (Nørrested 1996: 31). However, with the above in mind it is certainly fair to question his condescending verdict on Alice O’Fredericks’ and instead point to her ability to navigate a film culture fraught with prejudice and preconceptions.

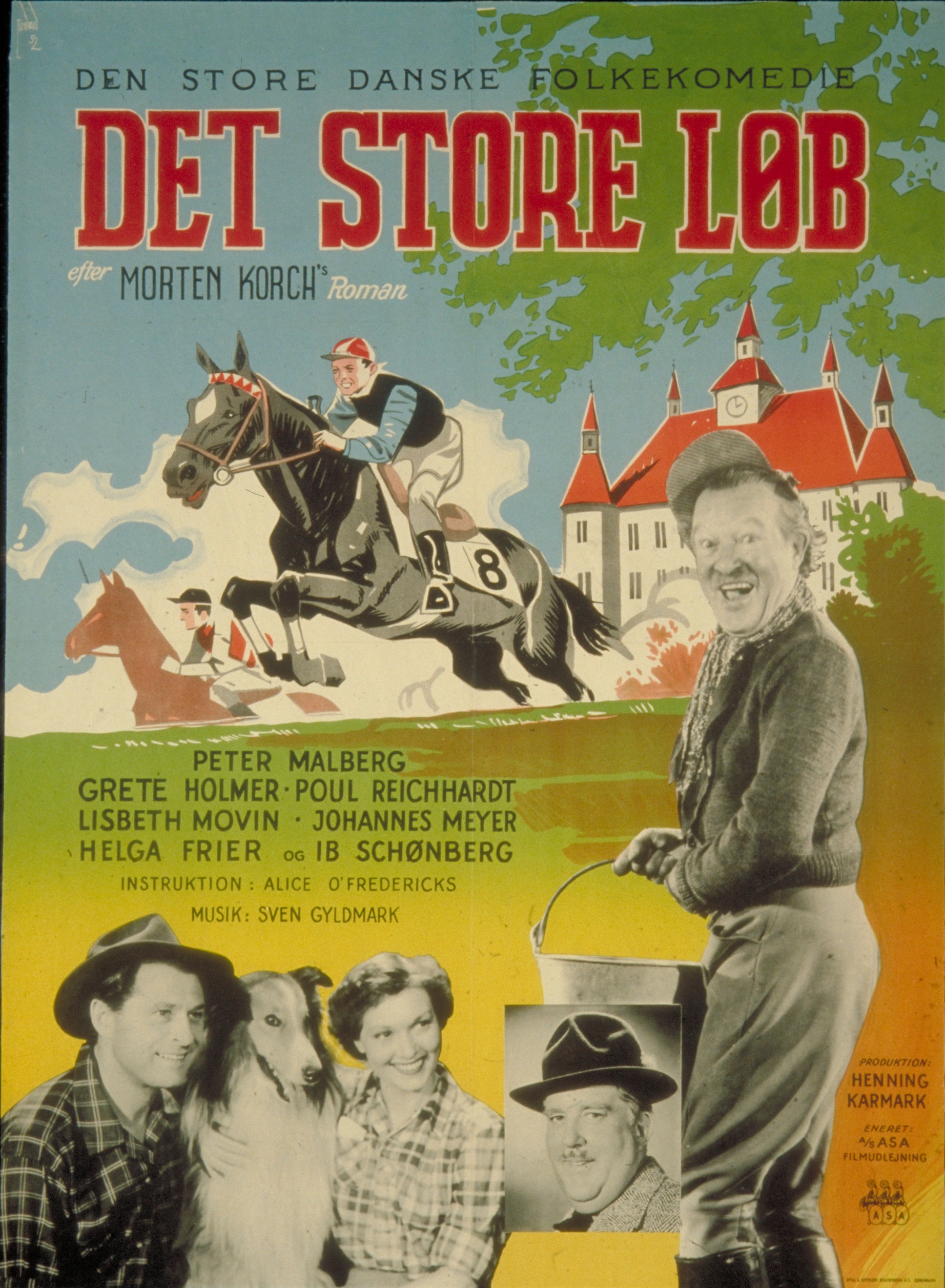

Morten Korch and the homeland genre

Morten Korch was the most popular living homeland author and had been trying to have his works adapted into film since the thirties. However, no one dared to tie in with someone whose naïve and easy-to-read novels were not considered to have any literary value and even were excluded from some public libraries from the forties and onwards (Rytter 1998: 34). After a deal with Jens Dennow failed, it was finally producer and ASA director Henning Karmark who, in the late forties, bought the rights to film Korch’s novels, setting up a consortium consisting of himself, ASA and Alice O’Fredericks as the series’ lead director (Pedersen 2012: 130-132). Together with sparring partners such as screenwriter Grete Frische and co-director Jon Iversen, O’Fredericks started working on the homeland film, which in the late thirties and forties had already proven its drawing power, especially in the Arne Weel-directed Den kloge mand (The Wise Man 1937) and Livet på Hegnsgaard (Life at Hegnsgaard 1938) (Hartvigson 2021a:106). The first Morten Korch adaptation was The Red Horses with a still unsurpassed success for a Danish film with around 2.4 million spectators out of a population of 4.2 million (Pedersen 2012: 140). Karmark/ASA/O’Fredericks were aware that they had a hit on hand and quickly followed up with another blockbuster, The Marsh King. Around this time the conflict with the capital’s critics began in earnest (Bondebjerg 2005: 121). The continuous success of the Morten Korch films throughout the fifties and into the sixties meant that Alice O’Fredericks became more and more unequivocally associated with what critics perceived as unassuming popular films. In reply to the criticism, O’Fredericks adapted a homeland film with more high-cultural aspirations, The Smallholder’s Girl. It was based on a short story, ‘Tösen från Stormyrtorpet’/’The Girl from the Marsh Croft’ by Selma Lagerlöf, who, as the first female Nobel laureate in literature, was known for endowing the epic with social criticism. The Smallholder’s Girl deals with a single mother’s struggle for social survival with her illegitimate child. In the title role, Grete Thordahl puts her body to the most explicit rape scene so far in Danish film, just as she tries to commit suicide. However, the film’s social aspirations and the use of Lagerlöf’s literary clout were downplayed by a critical Copenhagen press, which was quick to lump it together with the scorned Morten Korch adaptations (Pedersen 2010: 158). Alice O’Fredericks did not shy away from speaking out, as when she defended her films and the audience’s popular tastes in the National Tidende on 31/1, 1951. Here, she rightly calls for her films to be reviewed as the folk comedies that they are: “It is now clear that most of the critics do not like folk comedy, but I am saddened that they always scold the genre instead of judging the film a good, medium or bad folk comedy” (Pedersen 2010: 114). While critics at each new film adaptation denigrated the films and Alice O’Fredericks’ work as irrelevant and retrospective, audiences received Det gamle guld (The Ancient Gold 1951), Det store løb (The Great Race 1952), Fløjtespilleren (The Flute Player 1953) and Flintesønnerne (The Flint Sons 1956) with unabashed enthusiasm. The success continued through the fifties and sixties. From Kampen om Næsbygaard (The Fight for Næsbygaard 1964), Ib Mossin, who was the star of several of Korch films, became the director’s assistant/co-director on the films and continued after Alice O’Fredericks’ death with Korch films until the mid-seventies.

Alice O’Fredericks was responsible for collaborating with author Morten Korch during the preparations for the film adaptations. She recounted that the collaboration was very successful, as she was easily inspired by his romantic narrative form and positive-naïve outlook (Pedersen 2012: 136). However, from early on in the co-operation she implemented quite a few changes and modernization measures into the scripts (Pedersen 2012: 135). In connection with the premiere of The Flute Player, which has a profound plot and character changes compared to the novel, Korch nevertheless states his unreserved confidence in Alice O’Fredericks’ judgement: “How beautiful is this film, it throws sunstrokes into little things in life. Mrs. Alice has cherished the flowers that have blossomed in my heart” (Pedersen 2012: 135). The Korch brand was of great importance to the success of the films, and after his death, an agreement was made with his son Morten A. Korch that the Morten Korch films could be based on original screenplays, as long as they were also written and published simultaneously as novels under the Korch name. Thus, The Vagabonds at Hill Farm was launched as a Morten Korch film, while the novel was written by Alice O’Fredericks and Palle Kjærulff-Schmidt. This was also the case with the Næsbygaard trilogy and Brødrene på Uglegaarden (The Brothers at Owl Farm 1967) (Pedersen 2012: 581). In principle, this is the same idea behind Lars von Trier’s and Zentropa’s purchase of the rights to the Korch novels, which were designed for the TV series Ved Stillebækken (By the Quiet-Brook 1999).

The incredible dominance of homeland films in the fifties is also seen in the SAGA studio’s string of homeland films directed by Annelise Reenberg as Historien om Hjortholm (The Story of Deer Islet 1950), Fra den gamle købmandsgaard (From the Old Merchant’s House 1951), Den gamle mølle på Mols (The Old Mill on Mols 1953), Bruden fra Dragstrup (The Bride from Dragstrup 1955), Kristiane af Marstal (Kristiane of Marstal 1956) and Baronessen fra benzintanken (The Baroness from the Gas Station 1960) (Hartvigson 2022a).

The significance of landscapes

Alice O’Fredericks’ homeland films created timeless and utopian cinematic universes that combine present, dream, tradition and memory (Bondebjerg 2005: 104-105). The role of landscape and surroundings play extremely roles in the creation of the fictional universes. Alice O’Fredericks said in an interview in the Danish National Gazette from 1950 that the landscapes were essentially the reason why she took the job, and she talks about the joy of being able to work with the landscape as a motif: “The lovely landscape. I could photograph everything: the cornfields, the forests, the dikes, the mills and the animals with lots of sun, air and clouds” (Pedersen 2012: 137). Morten Korch is also aware of how the film medium, by combining action, characters, landscapes and music, helps the stories: “The plot of the film, the beautiful nature, the excellent music, everything, its spirit and its tone became a harmonious unit, the purpose of which was to bring cheerful entertainment and speak to the mind of the audience” (Pedersen 2012: 136). These seemingly banal statements conceal insights into the narrative and thematic significance of the landscape. This is especially true in relation to the characters of the homeland film, which are built around quite simple characteristics. In the absence of complicated, psychological traits, the characters become more rounded as they assimilate or reflect the surrounding landscapes (Hartvigson 2021a: 110). At the beginning of The Marsh King, where Hanne (Tove Maës) walks through the marsh singing ‘Hør det summer af sol over engen’/’Hear the buzzing of song in the meadow’, there are no complicated character traits to contradict the character’s lyrical celebration of nature, whose traits are readily mirrored and absorbed in her. Here Hanne becomes the eponymous young blonde girl from Den danske sang er en ung blond pige’/ ‘The Danish Song is a Young Blonde Girl’. The innocently convicted Jørgen (Poul Reichhardt) has been forcibly removed from his beloved nature during his imprisonment, and on his return, the directors Alice O’Fredericks and Jon Iversen, in their sure-fire staging of his reunion with Hanne in the marsh, provide an effective aesthetic development of the characters, whose bodies seem to grow together with and out of nature (Hartvigson 2007: 45)

In the sun-drenched, homely landscapes at the beginning of The Brothers at Owl Farm the musical landscape literally begets the flute-playing boy, Mikkel (Niels Hemmingsen), as he becomes synchronised with the musical landscape. This mysterious connection between characters and surroundings is in place from the debut with The Red Horses, where Ole Offor in the person of Poul Reichhardt arrives at Station of Lejre as the farm Enekær’s new foreman. From his first walk from the station to Enekær to his rehabilitation of the racing stallion Junker, there is a fusion between his character and the landscapes and animals which surrounds him. Ole Offor’s former identity as traveller, lover and pupil gradually disappears in favour of a psychological simplification of character, which in turn stands as an unambiguous extension of the farm, the landscape and their destiny (Hartvigson 2021a: 111). The connection is also obvious to the characters themselves, which is powerfully illustrated in Bente (Tove Maës) and Ole’s conversation about the typical Danish crops: rye, wheat, barley and oats. Their shared attention to and personal interpretations of the characteristics of the crops create an intimate space in which their emotional compatibility can be expressed (Hartvigson 2021a:110; Lefebvre: 29). During the conversation, close-ups of the crops are cut in, and the audience is invited to encounter Danish nature as living postcards reminiscent of old-fashioned school posters and pointing to both individual and cultural memory.

The scene is an obvious example of Alice O’Fredericks’ ability to activate the modernity of the film medium to give the homeland access to a Danish tradition and history. Morten Korch himself was surprised that this seemingly banal scene was not only included but allowed to take as much time, as it does (Pedersen 2012:139). In addition to allowing landscapes to serve as a background for plot and characters, O’Fredericks explores the symbolic, philosophical potential of landscapes. The films many lyrical compositions and musically scored nature montages draw on familiar landscape traditions, which recur from film to film, offering audiences an instinctive sense of cultural identity and national belonging (Hartvigson 2021a: 110; Lefebvre: 29). The film’s prominent music and songs add a lyrical dimension that appeals to audience participation and, in particular, to an emotionality in relation to the films’ national and cultural traditions (Hartvigson 2007: 26, 44ff). Producer Henning Karmark felt that one of the main reasons for their success was the fact that they in a sense resembled community singing, which had experienced a resurgence during the forties (Pedersen 2012: 132). Traditional Danish songs had always played a prominent role as background music or performed songs in earlier homeland films (Hartvigson 2007: 29, 49). From The Marsh King and onwards, the Korch series updates this tradition with Sven Gyldmark’s original music numbers such as ‘Jeg har min hest, jeg har min lasso’/’I Have My Horse, I Have My Lasso’, “Pigelil’/’Little Girl’, Du er min øjesten’/’You’re the Apple of My Eye’. These songs were performed with great success by actors Peter Malberg, Poul Reichhardt, and Ib Mossin and have become modern classics (Hartvigson 2021b: 69).

Erotic utopias

Alice O’Fredericks had no fear of sex and eroticism, witness her problem films, but she was certainly no fan of the direct and, in her opinion, unimaginative take on sex and nudity in modern Danish films, which she called “plump and unpleasant” (Pedersen 2012: 381). The erotic and the sexual is very present in the homeland films, but O’Fredericks strategy of activation avoided the explicit, as she used symbols, dramaturgical parallels and classic topoi to weave erotic and sexual patterns into homeland films’ visions of tradition and memory. O’Fredericks systematically used the link between nature and man, going back to the Song of Solomon, where the boundaries between man and surroundings are merged into a mystical unity. This archaic strategy of drawing character is quite different from the psychoanalytic characters with traumas, repressions and forbidden thoughts that were so well established from the early forties and onwards (Hartvigson 2013 b). Whereas the rural heroes and heroines are sexually and erotically restrained on a psychological level, the unconscious dimensions of the characters are determined by their dealings with animals and nature, and it is through this that they discover the erotic and sexual potential in each other (Hartvigson 2013a: 110; 2021a: 116). Alice O’Fredericks’ aesthetic ability to portray this coincidence between personal characters and surroundings explains how the genre’s simple characters can appear so attractive and fascinating.

The overlap between characters and surroundings is also expressed in the way the films systematically link attacks on and threats to property and landscapes, with bodily abuse of the homeland characters such as attempted rape or abductions. However, the destructive intentions of the abusers become thematically much more inscrutable, because on a dramaturgical level their actions function as a constructive sexual and erotic activation of the sexually reluctant hero and heroine (Hartvigson 2013a: 115; Hartvigson 2021a: 116). In Næsbygaards arving (The Heir to Næsbygaard 1965), the attempted rape of Rosa (Jane Thomsen), which is averted by her boyfriend Anker (Ib Mossin), initiates a marked sexual maturation of the young couple’s relationship (Hartvigson 2013a: 114). Obviously, such a vison of illegal and destructive sexuality as a prerequisite for normative heterosexuality has obvious queer potential. The erotic patterns of O’Fredericks’ homeland films have a strikingly queer potential and invite to see genre as a as a vehicle for sexual and gender negotiation. In the Morten Korch adaptations, a very prominent type of queering is found in the eroticized male relationship between the hero and a supporting male character typically a farmhand or a vagabond. In addition to the fact that these friendships are portrayed as intense and intimate, on a dramaturgical level they are parallels to and function in competition with the heterosexual relationships. From the outset, heterosexual relationships are much more confined and markedly less joyful. When they begin to work, the male relationship is typically dissolved, as the supporting male character leaves. In The Marsh King, Peter Malberg’s Sofus cycles into the horizon, leaving the hero in the arms of his fiancée. His leaving is comically presented as an anti-heterosexual stance, as he simply has had enough of his snivelling girlfriend (Grete Frische) (Hartvigson 2013a: 120). Strikingly, the male relationships are also presented through musical numbers which add a lyrical dimension and make them aesthetically facetted to a much greater extent than is the case with the male-female relationships. Fløjtespilleren (The Flute Player 1953) is about Poul Reichhardt’s amnesiac who is trying to rediscover his identity. The exhausted hero is taken in by a travelling circus, where the clown Laust (Peter Malberg) with patience and insight helps him get back on his feet. While he is soon recognized by his fiancé, he remains aloof towards her for a long time, only trusting Laust. Their solidarity and life together in the circus carriage and their circus performances as a couple with Laust in drag and a striking aestheticization of Reichhardt’s homeland hero, the male relationship is by far the film’s most elaborate.

At the end of the film, when the hero has become a farmer and husband, the film quite strikingly reminds us of the male relationship and the role played by Laust. While the hero and his wife stand on a hilltop and wave to Laust, who drives away in his circus carriage, the two men whistle a duet of ‘Fløjt om kærlighed’/’Whistle about Love’ as a farewell to each other. The song, which was their signature number at the circus performances. In flashback to before his amnesia the hero has also sung this song to his girlfriend, and this produces a striking intermingling of erotic energy across the hero’s heterosexual and homoerotic relationships (Hartvigson 2013a: 120-21). Under Morten Korch’s name, Alice O’Fredericks had written the original script for The Vagabonds at Hill Farm, and here she avoids the otherwise firmly established heterosexual takeover and lets a queer utopian household emerge at the end of the film. Poul Reichhardt and Ib Mossin are the vagabonds, Martin and Anders, who join forces in a joyful relationship, which includes musical performances, nude bathing and spending the night in a hayloft, complete with intimate conversations. Anders’ quest for family and home threatens to separate them. However, it turns out that Hill Farm with mother and daughter (Astrid Villaume and Githa Nørby) allows for double heterosexual housekeeping, while Martin and Anders can also continue their eroticised and emotional male friendship (Hartvigson 2013a: 122).

At a time when the heterosexual nuclear family had emerged as the dominant family form, O’Fredericks’ compound family-like entities represent a significant alternative that wonderfully combines tradition with a queer sensibility. These are typically broken biological multi-generational families who attract singles and outcasts with their hearts in the right place and where a queer interpretation is strikingly obvious, as these characters often defy gender norms and stand outside heterosexual logic (Hartvigson 2013a: 119; Hartvigson 2016: 258; Hartvigson 2021a: 114). In The Red Horses Maria Garland’s manly assistant renounces church attendance as well as heterosexuality. Armed with port wine, wreath cake and high spirits, she proclaims: “I have an appointment with our Lord. The day he lets me go to the altar as a bride, I will seek the church, not before.” In The Great Race, the suit-clad and determined Baroness (Helga Frier), and her unassertive and secretly over-eating brother (Ib Schønberg) form couples who defy gender norms, but with an unerring moral compass open their home to the hero and his horse when things look the bleakest. Faithfulness and morality also characterise the film’s many goofy male couples such as Ole and Nick (Ole Monty and Christian Arhoff) in Krybskytterne på Næsbygård (The Poachers at Næsbygaard 1966), who are simple-minded outsider figures and who, despite limited intellect, have a sure sense of good and evil, and they bear a great responsibility for the survival of the family. They are, however, out of heterosexual reach and their identical clothing and interacting couple dynamics more than suggest alternative cohabitation options that can be accommodated in the inclusive family units.

Father of Four

Alice O’Fredericks had long planned the Father of Four series with children and their families as the target group, but it was not until 1952 that she managed to find a constellation of children with skills and looks that could match Engholm and Hast’s popular comic strips (Pedersen 2012: 367). Far til fire (Father of Four 1953) was both a critical and box office success and paved the way for this first and much-loved children’s series, whose eight films sold 10 million tickets in its own time (Pedersen II: 376). Although there had been initiatives earlier with Sys Gaugin and Jon Iversen’s Hold fingrene fra mor (Stay Away From Mum 1951) and Vores fjerde far (Our Fourth Father 1951), it was certainly Father of Four, which manifested the family series’ popular impact and earning potential. The Father of Four became influential far beyond its time – including the extremely popular revival of the series between 2005 and 2020. An impressive line-up of heirs also includes SAGA’s My Sister’s Children series (1966-71) directed by Annelise Reenberg and its revival from 2001-2005, as well as Krummerne (The Crumbs 1991-2021).

In contrast to the characteristic timelessness of the Korch series, the films are based on modern and recognizable everyday life with school, table customs, family skirmishes, holidays and hobbies. In their own way, the films speak to a new reality of culturally progressive gender norms and, not least, a form of upbringing that recognises children’s creativity and does not subscribe to corporal punishment (Bondebjerg 2005: 127-8, 133). Alice O’Fredericks balances the modern and traditional by filtering the polarisation that characterises real-life cultural and social conflicts through episodic and comical short formats. that cultivate integration and conflict resolution with the logic and imagination of the child at the centre. A classic example is the meeting between Lille-Per (Ole Neumann) and the burglar (Poul Hagen) in the first film, where the child’s logic of borrowing and cleaning up quite disarms and charms the thief. Per’s need for help heating the cocoa transforms the criminal into a caring nurturer. On the whole, the children’s perspective of the series in every way reflects a solidarity with the adults and the surrounding community, and the films create a touching vision of social cohesion and solidarity between generations, which draws clear threads back to the folk comedy of the thirties and to Morten Korch adaptations (Hartvigson 2021b: 67). The Father of four‘s family unit is characterised by an absence of a mother, which is never mentioned, but nevertheless directs the audience’s attention to how the family behaves in her absence. On the one hand, the films also draw on traditional gender roles with the oldest sister Søs (Birgitte Price/Hanne Borchsenius) as a house fairy and substitute mother. Also, when apron-bearing Father (Karl Stegger) and Uncle Anders (Peter Malberg) try their luck at cooking sausages and potatoes in Far til fire på landet (Father of Four in the Country 1955) disastrous hilarity ensues. On the other side of what seems to celebrate the most conservative tradition, the film also negotiates masculinity, notably with the character of Father (Ib Schønberg/Karl Stegger) with the domestic and emotional responsibility and a family dynamic with children and siblings taking responsibility for their own and others’ upbringing. With the Father of Four series, Alice O’Fredericks doesn’t just deliver a vision of familiarity and community for children and all kinds of adults. These are folk comedies whose characteristic intensity occurs when the known is translated into stylized aesthetics and stereotypes and which count on and invite their audiences to engage in the fiction (Hartvigson 2005: 66; Hartvigson 2021b: 69). Alice O’Fredericks draws heavily on the comic’s episodic format and stylized aesthetic, and assisted first by Lis Byrdal and later by Grete Frische, she musters the entire arsenal of stereotypes, intertextuality and stylization into position with cute children and angry neighbours, exaggerated eyebrows and striped caps. When siblings Ole (Otto Møller Jensen) and Mie (Rudi Hansen) in Far til fire på Bornholm (Father of Four on Bornholm 1959) help Mrs. Sejersen (Agnes Rehni) out in a traffic crisis, everyone is staged with stylized postures, graphically distinctive textile patterns and hairstyles. Complete with a postcard-like Bornholm idyll as a backdrop, real life elements and experiences are transformed into drawn theatre.

Besides serving for lightning-fast identification of characters, situation, and mood, this comedy strategy serves to mark an openness to the audience and an invitation to engage with the fiction (Thomsen 1986:239; Hartvigson 2004: 80; Hartvigson 2005: 66). This engagement strategy, in which the film opens up to, acknowledges and invites its audience to participate, manifests itself not least in the children’s many apparently spontaneous singing and music performances. The films’ festivity and stylized unity are further enhanced through recognition and intertextuality. The most obvious example is the many joyous repetitions of Sven Gyldmark’s theme song ‘Det er sommer, det er sol, og det er søndag’/’It Is Summer, It Is Sunny, It Is Sunday’. In the family’s excursion to the Tivoli gardens in Far til fire i byen (Father of Four on the Town 1956), Father, Søs, Ole, Mie, and Per come walking ranked from lowest to highest to the beat of the Tivoli marching band playing ’It Is Summer, It Is Sunny, It Is Sunday’. When the real Tivoli marching band thus accompanies the fictional family who is in happy attendance, it creates an at once unexplainable and attractive mix of fiction and reality (Hartvigson 2005: 68; Kruuse 1964: 112). After the first film in the series, negative criticism grew from the influential Copenhagen newspapers, who were not enamoured with Father of Four’s well-groomed idyll and lack of any substantial problems (Nordin 1985: 33, Bondebjerg 2005: 134) The film’s display of positive family dynamics and singing children did not measure up to a modern perception of childhood and youth. The so-called golden age and children’s and youth films of the seventies and eighties (Christensen 2001: 129) thus owes much more to Bjarne and Astrid Henning Jensen’s films from the late forties De pokkers unger (The damned Kids 1947), Palle alene i verden (Palle Alone in the World 1949) and Vesterhavsdrenge (Westsea Boys 1950) with their social realistic and developmental psychology focus. However, Alice O’Fredericks’ popular legacy got a boost with eleven installations of the Father of Four series from 2005-2020.

Homeland film with children’s focus – the largest target group

Even though it was possible to grant tax exemption to children’s films, the committee responsible recommended that Far til fire og ulveungerne (Father of Four and the Cub Scouts 1958) should not be granted tax exemption due to the lack of quality in the educational content, even though it ended up getting it (Pedersen 2012: 374-376). Far til fire med fuld musik (Father of Four with Pipes and Drums 1961) did not get it and became the last film in the original series. The exclusive children’s film would be revived with SAGA Studio’s Min søsters børn (My Sister’s Children 1966) and the subsequent series, but from The Fight for Næsbygaard in 1964 at ASA, Alice O’Fredericks opened the melodramatic homeland genre to include a significant children’s focus up the. Her former sparring partner Jon Iversen had already made a touching prequel to this particular genre combination, which could appeal to audiences with an extreme age range. with the Palladium film Ta’ Pelle med (Bring Pelle 1952). This had also been the strategy when Alice O’Fredericks and Lau Lauritzen Jr. after the transition to sound film, Danish redefined film comedy with child star little Connie as central installation.

During a period of fierce competition from television, which was the Danes’ new preferred medium, O’Fredericks’ child-inclusive homeland films were surprisingly successful (Kau and Dinnesen 1983: 410, 478). In the Næsbygaard trilogy, Ib Mossin and Jane Thomsen are the young adults, and next to them O’Fredericks makes room for children of all ages, from teenagers in the figure of Ole Neumann as the illegitimate heir, Martin, and in The Heir to Næsbygaard Sonja Oppenhagen as the motherless and neglected Elise. The inspiration from Father of Four is particularly evident with Pastor Pripp’s (Poul Reichhardt/Holger Juul Hansen) musical girl children’s group, whose well-performed numbers such as ‘A baby – a baby!’ from The Heir to Næsbygaard was a hit with children, the child-loving and childish souls.

O’Fredericks had long been plagued by arthritis, and from 1959, the woman who at her most active had signed four annual films now made only one film a year. The 1971 The Brothers at Uglegaarden became her last film before she died in 1968. Her eagerness to make more films, despite her debilitating illness and an unsurpassed cinematic legacy, testifies to both an iron will and love for the collective way of working of the film medium. Ib Mossin made three more films in the Korch series, as well as continuing O’Fredericks’ line with Stormvarsel (Storm Warning 1968), a remake of Blaavand Reports Storm and a Far til fire i højt humør (Father of Four in High Spirits 1971).

When the Film Act of 1972 was launched to support a film industry in crisis partly because of competition from television, O’Fredericks had been dead for four years. However, with its support preference for realism and art film, “The World’s Best Film Law”, as it was called, was nevertheless a de facto frontal attack on the folk comedy and the popular culture that Alice O’Fredericks had come to be identified with (Pedersen 2012: 507). To this day her folk comedies remain so polarizing and the identification with them so attention-grabbing, that her ventures into social problem film as well as her experimental films are all but forgotten. It is likely not because of her gender – which she never wanted to be celebrated for anyway – but her affinity with low-cultural, that her uniquely successful career spanning five decades in an ever-changing film culture is as little celebrated as it is.

Author: Niels Henrik Hartvigson holds a Ph.D. in Film and Media at the Univeristy of Copenhagen and is a part-time lecturer at University of Copenhagen’s Saxo Institute and the Section of Film Studies and Creative Media Industries.

Litterature:

Bondebjerg, Ib 2005. Filmen og det moderne, filmgenrer og filmkultur i Danmark 1940-1972. Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag A/S.

Christensen, Christa Lykke 2021: Making a life of your own – Films for children and young people in the 1970s and 1980s, A History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh

Dam, Freja 2017: Hitmageren Alice O’Fredericks, Kosmorama: Hitmageren O’Fredericks | Det Danske Filminstitut (Danish Film Institute.dk) tilgået 20/5 2024

Dinnesen, Niels Jørgen og Kau, Edvin 1983: Filmen i Danmark Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2004: Lyst over Land – Det danske trediverlystspil og dets rødder i en dansk komedietradition Kosmorama 234, Danish Film Institute, Museum & Cinematek, s. 79-91.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2005: Konstruktioner og Maskespil – Komediekarakterer i film og teater in Kosmorama 235, Danish Film Institute, Museum & Cinematek, Summer, s. 59-69.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2007: Ph.d.-afhandling: 1930’ernes danske filmkomedie i et lyd-, medie- og genreperspektiv Faculty of the Humanities, Grafisk KUA.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2013a: Rural Intentions – Sexuality in Danish Homeland Cinema. Copenhagen: Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, Intellect, Ltd.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2013b: Nøglen til ethvert menneske -homoseksualitet og psykoanalyse i danske fyrrerfilm. In Kosmorama 250, Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, Museum & Cinematek.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2016: Queer teori og Baronessen fra benzintanken, MÆRKKserien: Filmanalysebogen, AAU

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2021a: Rural Dreams Homeland Cinema, History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2021b: The Danish folkekomedie tradition – the art of the popular, A History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2022a: Annelise Reenberg – First female cinematographer, leading director at SAGA Studio and interpreter of the popular: Nordic Women in Film Nordicwomeninfilm.com, Stockholm.

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2022b: Grete Frische – Med folkekomedie i årerne: Forfatter, instruktør og komiker: Nordic Women in Film Nordicwomeninfilm.com, Stockholm

Hartvigson, Niels Henrik 2023: Compound and Ambiguous Meanings in Cross-dressing Comedies in Journal of Scandinavian Cinema: Cross-dressing and trans-representation on Nordic screens, Copenhagen

Mariager, Tina interview 25/6 2024