Grete Frische, who died in 1962 only 51 years old, has one of the most interesting and least examined legacies in Danish film. As daughter of beloved actor, theater director and film writer and director Axel Frische, she was born into the popular entertainment business. As scriptwriter of several of the cherished Morten Korch homeland adaptations and the Far til Fire film (Father of Four series, 1953-58) Grete Frische incarnates the popular fictions called folkekomedie. Always very culturally divisive, Folkekomedie encompasses several popular film genres such as homeland films, sentimental comedy, farce and family comedy, as it draws on the culturally recognizable and relatable traits of Danish character types, traditions, customs, parlance and landscape (Hartvigson IV). Even when Frische’s work lies within realism and drama, such as the social problem film Vi vil ha’ et barn (We Want a Child, 1949) and the war drama Støt står den danske sømand (Stoutly Stands the Danish Sailor, 1948), folkekomedie clearly shines through. Likewise, the genre- and narrative experimentation of chef d’oeuvre Så mødes vi hos Tove (Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s, 1946) is thoroughly informed by broad folkekomedie. In her day Grete Frische was a notable media personality, who besides her film work was famous from radio, magazines, popular revue and as author of the autobiographical novel Vejen til Mandalay (The Road to Mandalay, 1942). At the end of her career, she related her career in twelve parts to an evening magazine. (Aftenbladet Søndag 1959).

Career

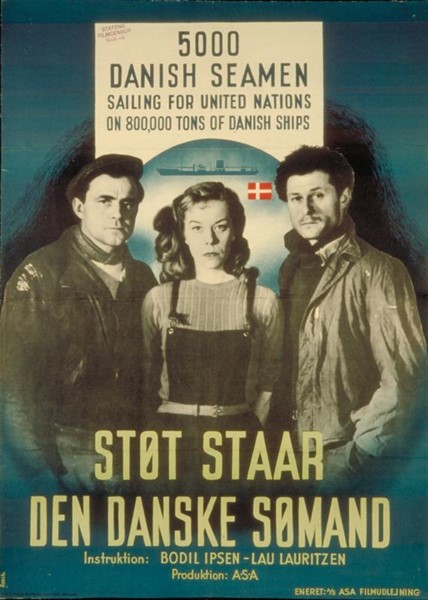

After a couple of attempts at an acting career, Grete Frishe started her apprenticeship at Nordisk Film, where she was assistant director for both the famed silent director Benjamin Christensen on Damen med de lyse handsker (The Lady with the Light Gloves 1942) and Emanuel Gregers on his Forellen (The Trout, 1942) and Alt for karrieren (Everything for the Career, 1943). She was noticed by ASA studio boss John Olsen and became an apprentice at ASA, based on a script for a transvestite comedy from an idea by Olsen, which she had written with her father. With its broad humour and stereotypes, the script, which would become the Christian Arhoff vehicle Moster fra Mols (Auntie from Mols, 1943), was a blueprint for a large part of the Saga films to come, and when John Olsen after his break with ASA founded the Saga Studio, Grete Frische was part of the package from the start. Male-female co-directors had proven hugely successful from the thirties with Alice O’Fredericks’ and Lau Lauritzen Junior’s collaboration on their string of folkekomedier at Palladium to the forties’ critically acclaimed collaborations between Bjarne and Astrid Henning-Jensen at Nordisk Film and Lau Lauritzen Junior and Bodil Ipsen at ASA. In this vein John Olsen made a directing couple out of Frische and the technically minded Poul Bang, who had also come over from ASA. Together they directed Saga’s first feature film, Kriminalassistent Bloch (Criminal Assistant Bloch, 1943), which she had written with her father, who also co-directed and played the title role. The film was well-received, and especially Grete Frische’s achievement was praised, and she was rewarded with her own project. However, the narrative and genre experimenting En ny dag gryer (A New Day Dawns, 1945) also became her last film at Saga. Frische, who always willingly made herself available to the press, characteristically downplayed potentially conflictual subjects (Petersen III) and insisted – just like studio boss John Olsen – that the break had been amicable. In any case, an artistic pairing of Bang and Annelise Reenberg, who would become top director at Saga in the fifties, would prosper much more than the one between Frische and Bang (Hartvigson V). Grete Frische considered working in Sweden but followed the advice of her father and returned to ASA, where she made her mark as screenwriter and co-director of Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s and as screenwriter of the commercially successful and critically acclaimed Stoutly Stands the Danish Sailor. As script-writer and idea-woman she worked in close collaboration with director Alice O’Fredericks and helped develop the extremely popular Morten Korch homeland adaptations and the Father of four series as well as the more critically acclaimed We Want a Child (with Lau Lauritzen junior as co-director), Fodboldpræsten (The Soccer Priest, 1951) and Min datter Nelly (My Daughter Nelly, 1955). For director and studio boss Lau Lauritzen junior, Frische wrote the manuscript for En sømand går i land (A Sailor Comes Ashore, 1956), which was remade in Germany as Das haut einen Seeman doch nicht um (That Doesn’t Blow a Sailor Over, 1958). She stopped working at ASA around 1958 and wrote the script for and played in Eventyrrejsen (The Fairytale Journey, 1960) produced by Palladium. She was scheduled to play in the sequel Eventyr på Mallorca (Fairytale on Mallorca, 1961) but took ill and was replaced by Clara Østø. In notable supporting roles she portrayed simple-minded, stubborn and sniveling characters, as well as creating her signature character, Snøvle-Sofie (Sniveling Sofie), with similar traits on radio and in popular revue.

Giants

In her career Grete Frische collaborates with the absolute giants of Danish film and entertainment. These contacts, who on the one hand gave her unique possibilities, also seem to have been a deciding factor in placing her in a more drawn back and supporting role, than the one she had at Saga and ASA between 1944 and 1946. Especially the period at ASA after her exit from Saga and the collaboration with Alice O’Fredericks comes to mind. O’Fredericks had an impressive output of both popular and serious films over four decades and depended on practical and creative collaborations. Over ten years from 1946 to 1956 Frische was an integrated part of the Alice O’Fredericks brand and had a determining influence in the creation of the Morten Korch homeland adaptations and the Father of four films, which represent an incomparable popular cultural legacy and continue to be cherished by the Danes. With an acute sense of the role of the script-writer Paw Kåre Pedersen writes that Frische was for Alice O’Fredericks what writer and novelist Johannes Allen was for Lau Lauritzen Junior and Bodil Ipsen, who represented the higher cultural sphere, witness the prize winning and critically beloved Cafe Paradis (Café Paradise, 1950) and Det sande ansigt (The True Face, 1951) (Pedersen II). It was therefore a rare occurrence that Frische was invited to write the Script for the Lauritzen and Ipsen directed – and equally prizewinning – Stoutly Stands the Danish Sailor, based on her brother’ and sister in law’s experiences as marines during the II World War.

In a female historical perspective Frische has slipped into the background of Bodil Ipsen, Alice O’Fredericks, Annelise Reenberg, Astrid Henning-Jensen and Annelise Hovmand, who are all her contemporaries with either longer directorial careers or in the case of Ipsen, Henning Jensen and Hovmand with high culture profiles. Frische may have been partly responsible for the lack of posthumous reputation, as she often downplayed her significant contribution to Danish film culture with a characteristic self-irony.

One big family

Frische gets her first acting contract at the Theatre of Odense, which her father, Axel Frische manages, and later, her entrance into the film business and her breakthrough as director, dramaturge and script-writer is certainly facilitated by her successful and popular father. Also, it is on his advice that goes back to the ASA studio after her years at Saga. There is no doubt that Grete Frische’s flair for teamwork and for lending her creativity to the projects of others are inspired by the close collaboration, which father and daughter develop and cultivate until the end of his career in the early fifties. In interviews she continually describes film-work as amicable and familiar, and stresses that her association with ASA is contractless, because ”why should friends have a contract”, and about her role as script-writer for O’Frederisks she relates, that it only natural that she should help out a girlfriend, who needs help (Pedersen II).

A probable consequence of Grete Frische’s obvious social intelligence was that she may have underestimated her status and abilities and let the opinions of others determine her choices. She herself related that the reason she did not continue as a director at ASA– apart from her bad health, which may have made the pressure from on-set film-work too great – was that O’Fredericks and studio boss, Lauritzen junior discovered her talent for writing. Her own subtly humorous description of her personality ”I am as docile as a Christmas-card and do what I am told” suggests resignation over and accept of others’ taking charge for her. This fits well with her self-proclaimed respect for ASA-boss Lauritzen Junior, whom she worshipped as a father figure, describing herself as his beloved and spoilt child, who is most content, when she is allowed to work in his office in his big work chair. Even when they were not in agreement, his authority was not questioned, as in the casting of Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s, when she was denied a major part by him and co-director Alice O’Fredericks, because they couldn’t see beyond her comedic persona (Pedersen II).

A distinct plainness

In a review of Grete Frische’s directorial debut Criminal Assistant Bloch Frederik Schyberg describes the film’s esthetical strategy as harbouring ”a distinct plainness”, and explains: ”There is a distinct effort to create a representation of reality, an everyday image in this crime film, which should be recognized. This is one of the paths to an improvement of Danish film. Out with cheap tricks: To make a simple film well is always better than trying to bake a bigger bread without the sufficient ingredients” (Petersen III). At a time where this genre was typically connected with dramatic characters and the big city, this film’s characters and milieu keep the crime story firmly planted in Danish provincial soil, as it celebrates the recognizable and relatable, be it an arch-typal fight at the local inn, realistic work-place depictions or down to earth elements such as the nasty cold of the main character, who coughs and hawks his way through the film.

Stereotypes, emotion and insight

It is likely one of the greatest scientific misconceptions that types and stereotypes should prevent intellectual and emotional engagement (Thomsen). Frische certainly had an acute understanding of the fact that broad characters and situations can disclose surprising nuances and achieve intense engagement. The very basic and repetitive construction of characters and situations of the Father of Four series splendidly demonstrates that audience engagement may very well spring from simplicity. Likewise, in the situation comedy-like opening from We Want a Child, Maria Garland’s ever delightful socialite housewife scolds Else Petersen’s daunted maid for not knowing better than to put coarsely ground salt on the table for the wedding. The obvious class conflict harbours a communication break-down between two characters who mirror each other in stupidity and lack of social intelligence. Also, Frische’s own portrayal of a maid, who chastises her mistress and master in Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s, combines the broadest humour with sharp social and psychological insight. Frische’s often coarsely drawn characters are directly recognizable and accessible but often with a surprising emotional potential. In A New Day Dawns, one feels both like laughing at and crying over how Frische’s Norma, who despite repeated defeats, has found pride in how she has been categorized by the education system: ”I am unintelligent, and I have the papers to prove it!”. In The Fairytale Journey, which is the last film she writes, one finds the simplicity in character and situations from the Father of Four series in the description of Danish holiday makers in southern Germany and Italy. However, the light tone, which dominates the film, is put in perspective by a death of one of the travel party. Also, a theme of segregation and its social and psychological repercussions is strikingly introduced, when the German Monika (Sonja Wiegert) recounts how her Danish family turned her away after World War II because of her nationality.

A distinct unevenness as artistic strategy

Frische’s folkekomedie films often display a distinct uneven aesthetic strategy, as they demonstratively combine crudely drawn characters, milieus and situations with realistic characters and full-blown drama. Creating a compound of genres and tones is a conscious artistic strategy that Frische sought from the beginning. For her directorial debut, Grete Frische chose to remake Carol Reed’s Bank Holiday (1938), which gives a kaleidoscopic view of holiday makers between London and the English South coast. As Reed’s original, A New Day Dawns spans very different genres from social problem films to melodrama and folkekomedie. The lack of sexual morals of the young generation are personified in Lily Broberg’s and Jørn Jeppesen’s characters and portrayed within the serious candor of realism and the social problem film. Meanwhile, melodrama governs the high-strung story of Grete Holmer’s nurse. She falls in love with the father of a patient, the widower (Erling Schroeder), who, after losing his son, tries to commit suicide, but is saved by the nurse in a dramatic rescue operation, which includes a lift with a jewel thief, arrest and last minute building ledge climbing recue. On the fringes of the social realism and the dramatic action, a host of Danish types lends the film a characteristic folkekomedie touch. Among these, Frische herself plays the not so fetching Norma, who snivelingly tells of working “as sort of a storage cnerk” [clerk]. When her female friend is seduced by a guy, Norma strikes up a new female friendship, and the two have a wholly unromantic sleep-over at the station at Tisvilde seaside resort. Where the sexual moral reflect a serious social issue, and the nurse’s story has enough drama for a season on a streaming service, Norma and the other types have a very different – recognizable and relatable – unimportance. The screen time allotted to the unexceptional types, the banal friendship quarrels and vacation disappointments parallels but also in a sense challenges the urgency of dramatic storylines and socially important issues.

Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s, which tells of a reunion of eight school friends, is with its flash-back structure and genre mix the most ambitious in supplying simple character and narrative set-up with unexpected dramatic openings. From character to character and story to story the film mixes genres and tones: Through the eye of Tudlik Johansen’s journalist we witness the realistically and harshly drawn workday of a washing woman; through Clara Østø’s spoilt upper-class doll we experience first-hand her slapstick traffic accident, and we follow the on and off stage romantic intrigues of operetta diva (Inger Stender). High drama surrounds Gerd (Gull-Maj Norin), who at school was the poor outsider with full scholarship, and who as an adult couldn’t bear to stay married to her first husband (Eigil Reimers), because he had killed her mother in a car accident. Now remarried, her new husband has given her renewed hope, which she is adamant she cannot survive without. However, the film ends by adding yet another blow to Gerd, as the affair, which had up to recently been attributed to the husband of the hostess, Tove (lllona Wieselmann), turns out to be that of Gerd’s husband. For a long time the film seems to go for a balanced palette of emotions and genres, which makes this tragic denouement all the more chocking and surprising.

Cultural status

The origin story of We Want a Child gives insight to the relative low cultural status of Grete Frische. From the start, ASA’s conception was to make a social problem film about parenting issues such as infertility, sex outside of marriage, abortion and illegitimacy to be written by Frische drawing on expert knowledge from doctor, Ib Freuchen. An economical incentive was the full exemption of entertainment taxes, which serious and societally important films were guaranteed, but in this case, it would not be granted before well-renowned writer Leck Fischer performed a rewrite with Freuchen. How much, if anything was changed, is uncertain, but in classic Frische style the film mixes genres and tones from folkekomedie, high-strung drama to documentary. The film was a huge hit, also internationally – in no small measure due to the explicit child birth scene – and reviewers were in awe of the film’ s humanity the enlightenment, allthough some were weary of the film’s mix of genre and tones. Even if a distinct compoundness dominates Frische’s work as director and script-writer, her signature is also found on more genre stringent works such as the homeland drama, Fløjtespilleren (The Flute Player, 1953), the comedy A Sailor Comes Ashore and the Father of Four family comedies.

Outside the norm

Grete Frische’s sensitivity to the outsider stands out in her scripts as well in the parts she plays. In A New Day Dawns she launches the character Norma Sørensen, whom she revisits in Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s, Mosekongen (The Marsh King, 1951) and The Fairytale Journey. With her characteristic nasal voice, Norma is simple-minded, unsophisticated, sometimes romantically interested but always romantically uninteresting and heterosexually disqualified. In Then Let’s Meet at Tove’s the ridicule of her speech impediment is the only male attention she is granted, and at the end of The Marsh King her finacé (Peter Malberg) cheerfully leaves her and bicycles towards freedom happily waving to the films main couple (Paul Reichhardt and Tove Maës). Film-expert Morten Piil is not very fond of the Norma-character, who, he feels, takes up too much space without being very funny (Piil). All the same, it makes sense that the character and screen-time she is allotted is part of a strategy, which insists on not reducing her to a forgettable background figure. Norma and other characters such as Betty Helsengreen’s housekeeper in We Want a Child or Jessie Rindom’s nagging widow mother in The Fairytale Journey have screen-time, which is not essential for the plot, but their insisting presence serves as testimonial to warped destinies and idiosyncratic life choices. When such characters in film after film use their screen time to be unresponsive to change and development, film theoretician Patricia White argues that it gives them a paradoxical representative strength as comparison and liberating un-normative alternative to heroines, who learn and develop, grow with their tasks, find love and meaning in life. Following this logic, characters like Frische’s single girl Norma with her independent life choices and absence of romantic relations arguably set a homosexual agenda for entertainment films or at least problematize their supposedly heterosexual vision. One certainly feels an intention of expanding the space for sexual and gender norms in her films. The Frische-scripted, A Sailor Comes Ashore is a bona fide bromance. A sailor (Lau Lauritzen Junior), whose best mate has died in a storm quits maritime life only to find he has an orphaned son, whom he takes in and names after his dead mate. A coincidence forces him to share quarters with another sailor (Paul Reichhardt), and an unconventional family unit develops featuring a lot of gender play and sexual innuendo. In Stoutly Stands the Danish Sailor the fierce competition between Paul Reichhardt’s Danish and Jørgen Frederik Ording’s Norwegian sailors turns out to harbor acutely warmer emotions for the survivor, when one of them is killed in action. Finally, Frische’s hand is clearly felt in the male friendship-romance emphasis of the Morten Korch homeland adaptations, The Marsh King, Det gamle guld (The Ancient Gold, 1951), Det store løb (The Great Race, 1952) and The Flute Player. The male friendships of these homeland films give us strikingly corporeal, intimate and performative friendships between Paul Reichhardt’s hero and Peter Malberg’s sidekick, which in many ways overshadow the much more downplayed heterosexual relationships of the films (Hartvigson I).

Author: Niels Henrik Hartvigson holds a ph.d. in Film and Media at the Univeristy of Copenhagen and is a part-time lecturer at University of Copenhagen’s Saxo Institute and the Section of Film Studies and Creative Media Industries.

Literature

Bondebjerg, Ib 2005. Filmen og det moderne, filmgenrer og filmkultur i Danmark 1940-1972. Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag A/S.

Dinnesen, Niels Jørgen og Kau, Edvin 1983: Filmen i Danmark. Copenhagen:

Akademisk Forlag.

Dyer, Richard 1999: The Role of Stereotypes in Paul Marris and Sue Thornham: Media Studies: A Reader, 2nd. Edition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Frische, Grete 1942: Vejen til Mandalay Poul Branner. Copenhagen.

Hartvigson (I), Niels Henrik 2013: Rural Intentions – Sexuality in Danish Homeland Cinema. Copenhagen: Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, Intellect, Ltd.

Hartvigson (II), Niels Henrik 2013: Nøglen til ethvert menneske – homoseksualitet og psykoanalyse i danske fyrrefilm. In Kosmorama 250, Copenhagen: DFI, Museum & Cinematek.

Hartvigson (III); Niels Henrik 2021 Homeland Cinema, History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh

Hartvigson (IV) Niels Henrik 2021 The Danish folkekomedie tradition – the art of the popular A History of Danish Cinema, Edinburg University Press: Edinburgh

Hartvigson (V); Niels Henrik Annelise Reenberg 2022 First Female Cinematographer, Leading Director at Saga Studio and Interpreter of the Popular: Nordic Women in Film Nordicwomeninfilm.com, Stockholm

Nørgaard, Erik 1971: Levende Billeder i Danmark Copenhagen: Lademann Forlagsaktieselskab.

Pedersen (I), Paw Kåre 2010: Unge Lau – Historien om filmmanden Lau Lauritzen Junior og ASA Film. 1 del 1910- 1945: Copenhagen: Books on Demand.

Pedersen (II), Paw Kåre 2012: Direktør Lau Lauritzen – 2. del af historien om filmmanden Lau Lauritzen Junior og ASA Film: Copenhagen: Books on Demand.

Pedersen (III), Paw Kåre 2016 m. Niels Jørgen Klement: Historien om Saga Studio – John Olsen-tiden. Copenhagen: Mellemgaard.

Piil, Morten 2001: Danske filmskuespillere. 525 portrætter. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Thomsen, Ole 1986: Komediens Kraft – En bog om genre. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

White, Patricia 1999: Uninvited. Classical Hollywood Cinema and Lesbian Representability. , Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Aftenbladet Søndag 1959. Copenhagen: Nummer 14-25.