In various texts and media Mirjami Kuosmanen is first and foremost titled as an actor, despite a career encompassing several roles in the film industry. On the Finnish National Filmography online site Kuosmanen is additionally described as a scriptwriter, assistant director, assistant editor and make-up artist.

Anni Mirjami Mielikki Kuosmanen was born in 1915 in Keuruu, a town in the central region of Finland. Kuosmanen came from a family with ten children and had a wealthy upbringing. Her father, Paavo Kuosmanen, was a successful manufacturer and owner of a local sawmill, up until the economic depression of the 1930’s. Out of six surviving children, Kuosmanen was described as the rascal who bent the rules of conventional behaviour. According to researcher Riikka Pennanen, in her article “Mirjami Kuosmanen – Suomifilmin tahtonainen”, Kuosmanen played sports with boys, put out a fire in the family’s home, drove a Harley Davidson, and her hobbies included horse riding, swimming and fencing.

Kuosmanen studied in Helsinki to become an actor – initially for the theatre – until 1938 when she was cast as a supporting character in director Teuvo Tulio’s screen adaption of The Song of the Scarlet Flower (Laulu tulinpunaisesta kukasta), and was irreversibly brought into the world of film. In 1939 Kuosmanen was cast as the lead in Nyrki Tapiovaara’s screen adaption of F. E. Sillanpää’s novel One Man’s Faith (Miehen tie) and got to know Erik Blomberg, the producer and cinematographer of the film. The couple got married in the fall of 1939, only two weeks before the Winter War broke out between the Soviet Union and Finland. Director Tapiovaara went missing at the battlefront, and Kuosmanen and her husband took over to finish the film. The death of one of the leading actors forced Kuosmanen and Blomberg to alter the script and re-shoot scenes, while preserving the main idea of both author Sillanpää and director Tapiovaara. In an interview in September 1989 with Tarja Savolainen in Suomineito zoomaa Blomberg stated: “we [Kuosmanen and Blomberg] worked together so that you would not know who did what”. During the shooting “I directed, decided the movement of the camera and the actors. Mirjami Kuosmanen directed the actors and the dialogue.” Savolainen then asked why Blomberg was credited as director, while Kuosmanen was credited as scriptwriter, to which Blomberg answered:

“For the opening credits we had to divide the roles. You could not say that the whole shebang was a collaboration of Mirjami Kuosmanen and Erik Blomberg: we decided together that I would be credited as cinematographer and director, and Mirjami Kuosmanen as scriptwriter and actress. This division was formal and made only because it was customary that a director and scriptwriter was separately mentioned in the opening credits. Of course Mirjami Kuosmanen did not do the cinematography. That was technique [may also be translated as technology]. Meanwhile, I did not act, since I was behind the camera. We did everything so closely together, that you would have to use tweezers to know what each of us did.”

Blomberg’s answers reveal how much Kuosmanen was involved with the production of the film, and in various roles as well. It is understandable that Kuosmanen’s talents were focused on acting while Blomberg was in charge of the cinematography. However, it is worth to point out the way Blomberg phrases this division: Kuosmanen did not work with the camera because of “technique” or “technology” (“tekniikkaa” in Finnish), and Blomberg did not act since he was working behind the camera, not because that was not his field of expertise. During the so-called golden age of Finnish film, from the 1930’s to the 1960’s, there were only four women who directed one film each: Glory Leppänen, Ansa Ikonen, Kyllikki Forssell and Ritva Arvelo. Naming Blomberg as the director of the film was probably a convenient solution at the time, but it is important to remember the consequences: the respected and prestigious title of a director will always remain his and give him a position of power and recognition that women rarely got during this time, and even today.

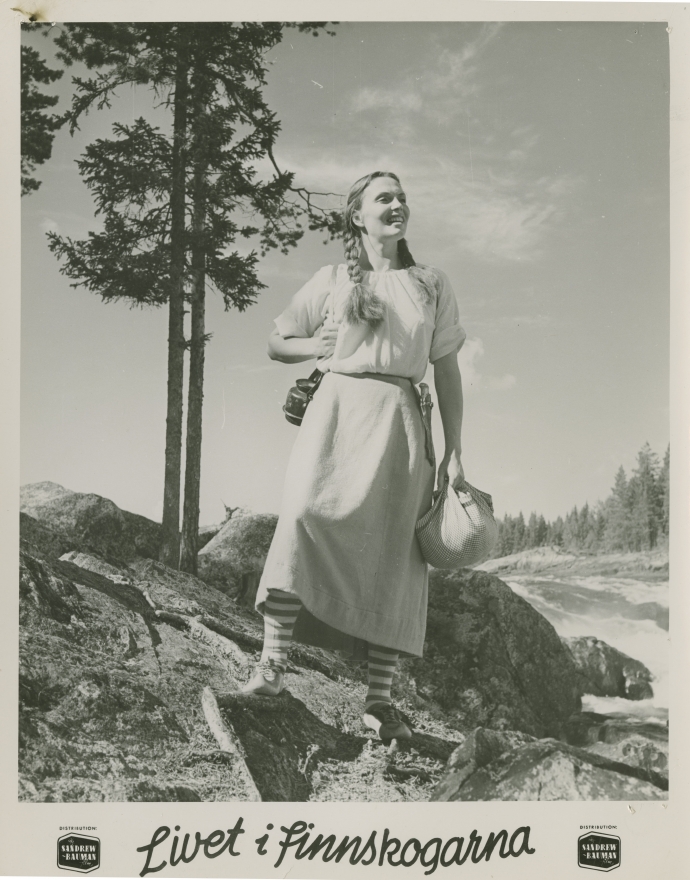

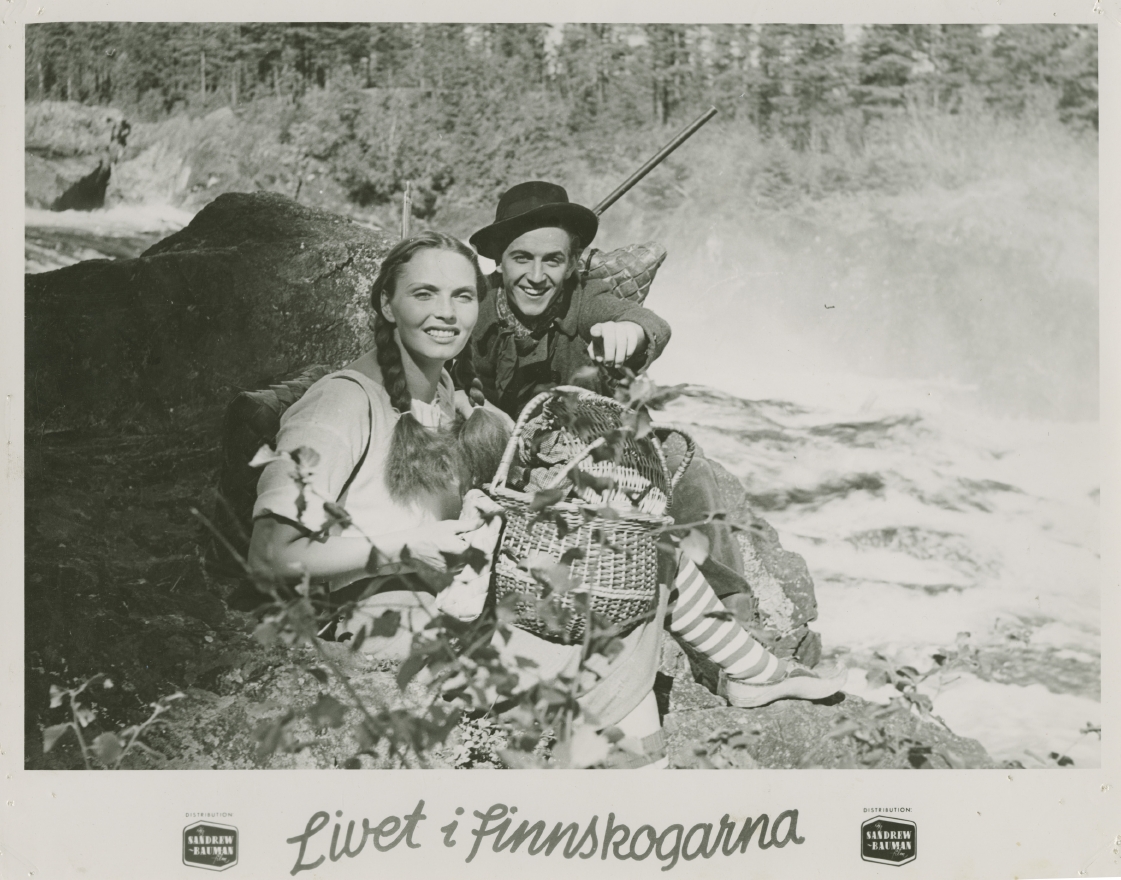

In July 1941 the Continuation War began, where Finland fought with Germany against the Soviet Union. The war ended in 1944. Kuosmanen gave birth to four children between 1941 and 1945 and acted in 12 films between 1940 and 1948. Kuosmanen’s leading role in the Swedish production Livet i Finnskogarna (Elämää suomalaismetsissä, Ivar Johansson, 1947) was seen as an achievement in Finland, and in Sweden she was called an “Esther Williams of Sweden”, after the American competitive swimmer and actor.

Kuosmanen and Blomberg continued to work together in the Lapland-themed film Arctic Fury (Aila – Pohjolan tytär, Jack Witikka 1951). The couple were unhappy with the film, but their dream of doing a well-made feature in the fantastic milieu of Lapland persisted, and later became the internationally successful The White Reindeer (1952). The White Reindeer was awarded with the Le Grand Prix International des Films Légendaires at the Cannes Film Festival in 1953; for its cinematography at the 8th Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 1964; and for Best Foreign Language Film at the Golden Globe in 1956. The film revolves around Pirita that marries the reindeer herder Aslak. Pirita feels lonely and visits the local shaman for help, but is turned into a shapeshifting white reindeer. The film ends in tragedy.

The idea for their film, according to researcher Sakari Toiviainen, was born when Kuosmanen, in a dream, saw a woman that through witchery could turn into a white reindeer. The film has been described as a successful outcome of the couples’ collaboration, not least by Blomberg himself in Suomineito zoomaa: “We both knew, from the beginning to the end, what every picture frame was. That is actually what the success of the film is based on.” Kuosmanen was from the start seen as the main character Pirita, and she developed the character for months. In the film magazine Filmihullu, film critic Aki Alanko states that because Kuosmanen’s work with the original idea, script, character development and acting, The White Reindeer “can well be seen as her film – her own ‘tour de force’”.

The White Reindeer became a success and gathered visibility at international film festivals, and the couple travelled on their own expense to Cannes. Mirjami Kuosmanen described the moment she was handed the award to the film magazine Elokuva-aitta in 1953: “As I was flustered I said my greetings from Finland – in Finnish. A surprising silence in the audience, and then cheerful laughter. After a few moments of thought the boys took this as quickness. I continued in English, and I felt that they accepted me.”

In the 1950’s Kuosmanen continued to work on several films together with her husband, and in his article in National Biography of Finland, researcher Sakari Toiviainen describes Kuosmanen as an “equal partner and collaborator, actress and scriptwriter” to Blomberg. For Aki Alanko the 1950’s “produced her biggest artistic achievements”. In an article in Suomen Sosialidemokraatti in 1955 journalist Inkeri Lius states that “the couple Mirjami and Erik Blomberg are doing fruitful cultural work by getting the general public acquainted with Finnish classics through the medium of film.” According to her husband, Mirjami Kuosmanen was very well acquainted with Finnish literature. When There Are Feelings (Kun on tunteet, 1954) was a screen adaption of ten short stories by author Maria Jotuni, which Kuosmanen wanted to turn into a feature film combining several characters. In an interview with Sakari Toiviainen, Blomberg stated that Kuosmanen had an excellent ear for languages and a mastery of the Finnish language. Thus, Kuosmanen was in charge of the adaption from literature to film and was the one who reworked the dialogue for the actors. According to Toiviainen the portrayal of women in Jotuni’s texts are one of the most wonderful portrayals in all of Finnish literature history, and through Mirjami Kuosmanen’s adaption and the amazing actors these women are now portrayed in Finnish film as well.

After the success of When There Are Feelings Kuosmanen and Blomberg began the next adaptation project: Bertrothal (Kihlaus, 1955), based on Aleksis Kivis play from 1866. Kuosmanen’s last screen adaptation was a Finnish-Swedish-Polish collaboration, Wedding Night (1959), based on Émile Zola’s short story L’attaque du moulin (1892).

Mirjami Kuosmanen passed away in 1963 at the age of 48 when, fitting with her active image, she was swimming at the Helsinki Swimming Stadium and passed out in the shower. In Riikka Pennanen’s article “Mirjami Kuosmanen – Suomifilmin tahtonainen”, her son Erkka Blomberg depicted his late mother as “an amazing diva with a strong will and opinion”. Kuosmanen’s activities in the productions she worked on together with her husband, has been portrayed as a “central behind-the-scenes operator” or someone in the background, not quite the central figure. Kuosmanen worked during a time when there were practically no women film directors in the Finnish film industry, and when the technical aspects of filming and camera work were regarded as hard for women to understand. Undoubtedly, Kuosmanen had an essential, creative part in several Finnish feature films, and she is to be regarded as a talented personality that left a mark within Finnish culture, and for generations of women in the film industry to come.

Anna-Sofia Lappalainen (2020)

References

Written sources:

Rytkönen, Sisko. Ihanat naiset kankaalla – filmitähtiä suomalaisen elokuvan kultakaudelta.

(Hämeenlinna: Karisto Oy:n kirjapaino, 2008.)

Saarinen, Heli. “Valkoinen peura ja Olaus Magnuksen Lappi-kuvat.” In Valkoisen peuran myyttinen Lappi.

(Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press, 2011.)

Savolainen, Tarja. “Vauhdikas, jännittävä, hauska ja syvästi inhimillinen elokuvakertomus esiäitiemme Suomesta.” In Suomineito zoomaa, edited by Marja Niemi and Riitta Oittinen.

(Helsinki: Kansan sivistystyön liitto, 1990.)

Toiviainen, Sakari. Erik Blomberg.

(Helsinki: Valtion painatuskeskus 1983.)

Websites:

Pennanen, Riikka. “Mirjami Kuosmanen.” Elonet.

(elonet.finna.fi)

Pennanen, Riikka. “Mirjami Kuosmanen – Suomifilmin tahtonainen.” Seura. (seura.fi)

Sundqvist, Janne. “Ensimmäiset neljä naista – vain he saivat ohjata suomalaisen elokuvan kultakaudella.” Yle Kulttuuricocktail. March 24th, 2017. (yle.fi)

Toiviainen, Sakari. “Kuosmanen, Mirjami (1915-1963).” Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu (National Biography of Finland). (kansallisbiografia.fi)

Newspapers and magazines:

Alanko, Aki. “Mirjami Kuosmanen – Suomi-Filmin suuri kohtalotar.” Filmihullu 2/2004.

Kuosmanen, Mirjami. “Cannes.” Elokuva-aitta 12/1953.

Lius, Inkeri. “Mirjami Kuosmanen.” Suomen Sosialidemokraatti 252, September 1955: 10.

Basic info

Main profession: Screenwriter

Born: 1915

Died: 1963

Active: 1938-1959

Filmography

Screenwriter:

Wedding Night (1959)

Bertrothal (1955)

When There Are Feelings (1954)

The White Reindeer (1952)

Actor:

Something in People (1956)

Bertrothal (1955)

When There Are Feelings (1954)

The White Reindeer (1952)

Arctic Fury (1951)

May Magic (1948)

The Singing Heart (1948)

Leeni of Haavisto (1948)

Through the Fog (1948)

Livet i Finnskogarna (1947)

Tösen från Stormyrtorpet (1947)

The Gold Candlestick (1946)

Kohtalo johtaa meitä (1945)

Sinä olet kohtaloni (1945)

Yrjänän emännän synti (1943)

A Foxtail Under the Arm (1940)

Miehen tie (1940)

Men Are Gullible (1939)

Two Henpecked Husbands (1939)

The Song of the Scarlet Flower (1938)