Mai and I both wanted out of our childhood surroundings. There just had to be better worlds out there than the one we inhabited. We had both hated school, had both had a hard to time getting friends, had both felt like outsiders. Our living conditions were similar. Mai lived in the Södermalm part of Stockholm, in a two-room flat across the yard. Whether our ambitions were dictated by particular social circumstances, I don’t really know. Would our yearning for something else have been different, had we grown up in a well-to-do milieu, surrounded by books, music and good taste? Would we then, like many bourgeois children during the 1970s did in order to protest, have looked for work in factories in order to get to know the workers conditions? Highly unlikely.

Getting to work with theatre was a great liberation for both of us. Mai and I presented similarly poor school results and decided to educate ourselves together. Out loud, we read the chamber plays of Strindberg, line for line, play for play. We would often be at Mai’s place. We’d lie on the floor, on our elbows, leafing and reading, hour after hour. For a long time, those plays would flow together in a blur to me. “Storm”, “Burned House”, “The Ghost Sonata”, “The Pelican” and “The Black Glove”. We then proceeded with “The Bridal Crown”, “Swanwhite” and “A Dream Play”. We got through Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt” in Norwegian. That one took a little extra time, as we didn’t quite grasp some of the words; rather we had to guess our way around. We had long and extensive talks regarding The Meaning of Life. We read the novels by Joan Grant and wondered if we had known each other in a previous life, possibly explaining the close kinship we felt we had!

According to my diary notes of early 1942, Mai and I walked the hot and dusty streets in the direction of the Djurgården area. We were the only pupils at the Calle Flygare theatre school who couldn’t afford a vacation trip. We longed to get out to the archipelago, but the fare of the white boats was too steep. We trudged out to Djurgården, thus saving the price of the blue tram trains.

In an earlier diary, from when I was 15 years old, I described Mai as: “Petite and in fine fettle. Blue eyes. Fair hair. Small cute mouth, very beautiful teeth. Small, small adorably sweet hands. Upturned nose. She’s got two little cute dimples in her cheeks. Mai’s looks shifts at times. In general, she’s awfully pretty.”

In the late summer. Mai, Bojan Westin and a guy named Börje Nilsson had a premiere at the Gröna Lund amusement park. Calle Flygare had assembled a small song-and-dance matinée programme, held at the stage where trapeze and pole artists would swing around and dive into water barrels during the evening shows. “Uncle Calle” himself was the master of ceremonies, geared up in a dressing-gown coat and a red fez with a little tassel. Then Mai and Bojan would enter the stage, dancing and singing “Tuttan and Ingeborg, two little girls…”. The ladies in the audience were delighted and clapped heartily. As for me, I was engaged as stage manager and dresser at this spectacle. My pay was five kronor and a free pass for the carousels. Mai got 15, I think. To me, the carousels and the roller coaster was the prime highlight of the evening.

Came September, and Mai applies for the Royal Dramatic Theatre Training Academy. She’s among the youngest ever accepted. She was just 17 and had read a scene as Eleonora in Strindberg’s “Easter”. “And she does it so indescribably beautifully… So she should be in by now”, I write in the diary. I have already bought her flowers, I’m that certain of her success. Now and again, I interrupt my diary writing to go out and call her on the phone. Finally, there’s an answer, and I’m let to know that she made it. “I’m so happy for Mai, it feels more or less like I got in myself. Lucky, lucky Mai!”

At the time, I was 15 and still with Calle Flygare. Two years later, when I could have made a tryout at The Royal Dramatic Theatre myself, I already had gotten a trainee contract with SF, Svensk Filmindustri, at 200 a month, and additionally also had made my stage debut as Anja in Chekhov’s “The Cherry Orchard” at the Blancheteatern theatre.

In the summer of 1943, we rented a one-room-with-kitchen from an old woman out on the Blidö island in the archipelago. Mai had spent the spring doing work as an extra at The Royal Dramatic Theatre with a promise of a main part come autumn. She had also gotten film offers. As for me, I’d just signed the contract for my first film role in The Word (Ordet, 1943) and would get 75 kronor per shooting day. We felt wealthy. We could afford ourselves the luxury of a week-long vacation. During the long bright evenings, we would wander through woods and across meadows. We brought paper and pen and would stop and draw a tree or write a poem. When we returned to the cottage in the bright twilight, it would be too murky to be able to read anything. We would light candles, write some more in our diaries, and attempt to improve our poems.

Many years later, Mai told me how upset she’d been on one of these evenings at Blidö. We had, as usual, been writing on our poems. Mai read her results to me. Then it was my turn to read out my poems to her. But I refused, probably because I felt they weren’t good enough. From the start and most naturally, Mai was the most artistically talented of the two of us, as an actor and as a writer. I was embarrassed of my own achievements.

Via the Lemkow brothers, who had escaped across the Norwegian border with their father, we would get closer to the war. The Lemkows were Jews. The mother, who was sickly, and the sister, who had a Norwegian boyfriend, chose to stay in Norway. Only the men were at risk of being taken, so it was rumoured. So the father and the sons escaped. Six months later, they found out that the mother and the sister had been picked up by the Gestapo. They were never heard from again.

We would see the Lemkow brothers quite frequently. Mai fell seriously in love with Tutte. They got married and moved to a cottage in Ålsten. Soon Mai was expecting, and gave birth to her daughter Etienne. She was 19. Mai left a void, now immersed by her new existence.

Mai moves with Tutte to England and our contact decreased. I myself got married and had children. From the diary, September 1947: “Mai’s first English film Frieda premiered at Spegeln this evening. I am happy for her success. At the same time, I feel happy that she can express something that I myself want, but can’t, yet. Maybe never? I sensed that Mai would become a great artist already when I was 14 and first saw her in a scene at Calle’s. This is the best thing she has done so far. But she will be even bigger.

Our friendship over the years faltered along. From the diary, from London September 1952: “Nils and I are leaving today after a pleasant week in London. Have met Mai. She has changed a little, become more independent. Formed very definite opinions about things. Herbert Lom has meant a lot to her, she says. Yes, maybe more than she thinks. He has not only helped her dare to be herself. He has also given her opinions. I like her a lot, as I always have. But there was something that… that I can’t quite define. Or was it just that we had too little time? Too few minutes for ourselves? She went to Hamburg the other day to do location shots for her next English film, a thriller with Dirk Bogarde.” (Desperate Moment, 1953).

This was in the middle of Mai’s movie star period. Mai had busy times. During my visit, Mai was offered a girl role that would have a Swedish or German accent. Mai was unable to play the role due to other commitments. I interpreted the fact that she did not recommend me to apply for the role to mean that she did not consider me to be a good enough actress.

Mai talked about her relationship with Herbert Lom. He was a communist. Mai got down to business and gave me a lecture. I felt increasingly disheartened by her obviousness. But Mai was completely filled up with her new ways of thinking, trapped in her own world of ideas and entrenched within herself. But Mai also had a strong belief in herself and her own possibilities. She was brave. She worked very hard at times. And above all, she has a belief that she has something important to say. The fact that Mai held monologues and did not always communicate with her audience did not break up our friendship.

A Copenhagen encounter together with our mutual friend, director Barbro Boman. Mai and the writer David Hughes, to whom she was married at the time, drove from Sweden, spent the night and then went home to Provence. Mai had seen Kjell Grede’s film Hugo and Josephine (1967), which I really liked. Mai spewed hostility over this, in her opinion, atrocious film. She viciously and mockingly imitated the children in the film. I was upset, because I had seen how nicely Kjell Grede worked with the children, because I had a small role in the film. The atmosphere between us became irreconcilable. I found Mai lacking in generosity when judging other filmmakers.

When I visited her in France in the summer of 1970, it was Vilgot Sjöman’s turn to be executed, for the I’m Curious films. We drove around in the south of France to look for locations for Mai’s planned film about van Gogh. In addition to Mai and David, the photographer John Bulmer and his girlfriend Mary were also along on the trip. I took Vilgot in defense. Mai retaliated by freezing me and my attempts at conversation out.

After participating in the Marche pour le désarmement French peace march in the summer of 1981, I called Mai from Paris. She had welcomed me to her new place of residence Le Mazel in the Ardèche. This would be a good time to visit. Mai’s home was on its good way to become as beautiful as the one she had created in Provence. She had a genius for finding old houses and then refurbishing them bit by bit. Her young lover Glenn, who was a stonemason by trade, had laid beautiful tile floors on the ground levels. But it was Mai who planned how the houses would be renovated and furnished. I remember the big beautiful room with an old fireplace from the 17th century. From the CD player music by Bach flowed ut. On a heavy, brown-stained table, art books were spread out next to a tall vase of sunflowers. There’s a stale smell from the water in the vase and the books are dust-ridden. This blend, to me, is very typical Mai.

I missed David, her ex-husband. And maybe Mai did too. He had broken up several years before, when they were still living in Mas d’Aigues vives. He found it increasingly difficult to write, had to return to England and his own language, he said. Mai had books approved, while his manuscripts were rejected. She managed to realise her film projects and arranged for David to be employed as a still photographer on the shoots. Life was lived on her terms.

Sigtuna, February 11, 1983: Mai Zetterling, my close friend during my teenage years, has lived here in the apartment for three days. She was picked up early this morning by a taxi, which drove her to a live interview at the morning news show. The reason is her participation in the Women’s Film Festival in Stockholm, where her new English film Scrubbers (1982) is being screened. She wants to go to Sigtuna to work. We went up to the Sigtuna Foundation’s library and borrowed books about and by Agnes von Krusenstjerna, for a film idea she has. Mai skims the books – a technique I never managed to learn. In fifteen hours she cuts through books that would take me weeks of concentrated reading.

Otherwise, we eat well, drink wine or tea and talk relaxedly. Mai creates a creative atmosphere around her. She says on the phone to others she talks to that she ‘works like an animal’. She is working on the last chapter of her autobiography “All those tomorrows”. A few years earlier, she had the idea to ask some of her friends to each write a chapter about her. Would I like to contribute? She had also asked Sheila La Farge and David Hughes. Time was tight. She wanted it before Christmas and asked me to concentrate on the years when we went to Calle Flygare’s theatre school. I looked up my old diaries and let this work of putting together a chapter for Mai’s book take up all my free time. I sent off my script by Christmas.

It wasn’t until much later that I understood that Mai wanted my chapter as soon as possible, because at that time she intended to start writing about her teenage years herself. She needed reference points for memory. She abandoned the idea of friends’ contributions. Of my fourteen pages a few quotations remained.

One night when I got home from the Unga Klara theatre, where I played Julia in Lars Norén’s “Underjordens leende” (“Smile of the Underworld”), we drank tea instead of red wine with our sandwiches. We both had trouble falling asleep. Mai claimed she’d only slept for three hours. But she had felt creative, got lots of ideas and wasn’t tired at all. For many years she says that, like Napoleon, she only needs five hours of sleep. She has trained herself not to sleep anymore. She uses her time by working. Outstanding…!

The day before, Mai has met her mother Linnéa, whom she loathed. She learns that she had a four years older sister who was put up for adoption and grew up in Skåne. The sister’s name was Inga!

February 18, 1983: “Mai was at the performance of our Norén play last night. Then we had supper next to the theatre. It was a good get-together. Mai was in a good mood. She had signed a contract for the film about Agnes von Krusenstjerna. We cleared up the old grudge. And we felt that there’s a solid and lasting foundation in our friendship. The loyalty from the youth remains at the foundation.”

And then Mai’s autobiography, called “Osminkat” (“Without make-up”) in Swedish, was published just over a year later. I read, impressed and captivated, the account of her childhood and early adolescence. There was much to reflect on here. The loneliness, the self-loathing, the lovelessness and the disgust. In the chapter on Calle Flygare, I found a short section from my script that contained a testimony to the great, indescribable experience of the light that entered Mai’s life. Further on, to my surprise, I found a wording that made me stop and read again and again: “I worked hard on instinct and used the pain of the past to communicate – that is, on stage. In real life I was still out of touch with people. But I started a kind of friendship with a very talented girl in my class at Dramaten. Her name was Anita Björk and she would later become a big star. We are still friends.” This sisterhood of hers and mine, which I thought was mutual, thus did not exist for Mai! This is how we live our performances. It was instructive. When I told Mai about my dismay, she replied that she couldn’t write about everything.

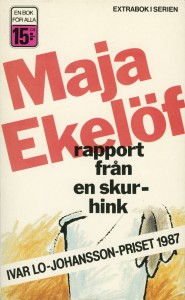

November 24, 1989: Mai flies in from London. I’m picking her up at Arlanda. We go home to Sigtuna. She stays with us for a few days to write a brief synopsis of Maja Ekelöf’s book “Rapport från en skurhink” (“Report from a Scrub Bucket”). I’m cleaning it up for her at the typewriter. She goes to Stockholm, talks to Ingrid Edström and Peter Hald at the Film Institute, talks about her plans for the film and that she wants me in the lead role as Maja. Ingrid Edström accepts and is interested in the idea. Mai gets the affirmative green-light to write a script. She is enthusiastic about her meeting with Ingrid. To finally meet a woman with a braid down her back in the executive room! For me, I am pleasantly surprised to get the offer to play Maja, as Mai had previously only requested me for supporting roles, in Loving Couples (1964) and Amorosa (1986). Now she expresses her joy that we will work together. She also wants to include Margreth Weivers and Bojan Westin as Maja’s friends from Karlskoga. The little sisters from Calle Flygare’s theatre school are to unite in front of and behind the camera.

Even though Maja Ekelöf’s conditions were so much harsher than mine, and her courage so much greater, she feels closely related. I share her naivety, her pessimism and her will to fight against the irrationalities of the world. The script should be ready in April and Mai expects to shoot the film during September-October 1990. In order to meet Maja Ekelöf’s children, Mai goes to Karlskoga. She sends me off to the Newspaper Dagens Nyheter´s archives to look for newspaper clippings about Maja and make copies of them. I do this with pleasure. It is in my own interest to find out as much as possible about this woman I will portray. I am also reading Maja Ekelöf’s second book, the exchange of letters with the convict Tony Rosendahl.

Mai gets the idea that Maja should converse with Sara Lidman in a fantasy scene. She asks me to arrange a meeting with Sara, as she knows that we’ve known each other for many years. We are invited to dinner at Grete Almgren’s house at Långholmen, where Sara stays during her Stockholm visits. Sara shows tender affection for her elderly friend. Half of her listens to Grete, while Mai talks about her film plans. Sara contributes some snapshots from memory of some meetings with Maja in the 1970s.

Mai has a lot to manage during her stay. After seeing a close-up of herself in an English film about witches (The Witches by Nicholas Roeg, 1990), she had made an appointment for a “chin lift”. She had received the tip from a colleague who had some skin cut off her neck with good results. I did a visual inspection of my own embryonic turkey neck and realized that it might be necessary for my part as well.

– You mustn’t do that before we have shot the film about Maja, said Mai.

– She was actually only 50 when she wrote her book, I objected. And I’m over 60!

– Yes, but she was worn and looked much older.

– True.

After a three-week period when Mai lived either with us in Sigtuna or with the production manager Brita Werkmäster in Stockholm, she flies off to London for a few shooting days and then returns to her house in France to write the script. During this writing period, we call each other from time to time. The work is going well, says Mai. She feels inspired. At the beginning of April, Mai arrives in Stockholm again with her finished manuscript. Ingrid Edström and Peter Hald at the Film Institute are not quite satisfied. Mai herself suggests changes and says she would like to rewrite the script together with David Hughes. She gets the funding. The manuscript is to be submitted in June.

We have lunch with Margreth (Weivers) and Bertil (Norström) together with Bojan. We are talking enthusiastically about this upcoming work. We all have roots in Maja’s working class. Also it’s wonderful to work together again after all these years! Calle Flygare smiles in his heaven, muses Mai. The collaboration with David is going slowly. He has some articles to write – and he also drinks too much, according to Mai’s phone reports. The script won’t be finished in time, and it’s David’s fault, says Mai. She predicts that we will probably have to make do of only shooting the scenes in the lingonberry forest at the end of August, and then continue filming in November, as she needs the intervening months for preparatory work.

I have turned down roles at Stadsteatern (the Stockholm City Theatre) in order to keep the autumn free for the film. But August passes before they have produced a script, and Mai now says that we probably can’t start the film until January. In the meantime, articles appear in the press that the film institute no longer has any production money.

In October, I’m trying to approach Ingrid Edström to hear what the possibilities look like for the film to actually start in January. They have not yet decided on the delayed script. I can’t get hold of Ingrid, instead I call Mai and say that I need a preliminary stance on whether I should take a leave of absence from Stadsteatern during the spring season – or go into rehearsals for Per Anders Fogelström’s “Remember the City”, which is expected to premiere in February 1991. Mai doesn’t want me to talk to Ingrid Edström, but she admits that we’ll probably have to wait until next summer for the shoot.

From Peter Hald, Mai eventually receives a thumbs-down after he reads the revised manuscript. Ingrid Edström does not contact us at all. Mai feels badly treated. At an early stage, she contacted TV and presented her Maja Ekelöf idea. Ingrid Dahlberg has announced that she is not interested. Mai curses Sweden, which doesn’t believe in her, even though she showed what she can do with Loving Couples, The Girls (1968) and Amorosa. Bengt Forslund is the only one willing to invest a few millions from his Nordic Film and TV fund on “Maja – a cleaning lady in the world”. Bengt certainly thinks, like me, that the fantasy episodes have become too many and are both overwhelming and costly. Maja herself has lost contact with the ground. A low-budget film has blown out of proportions.

After not very long, Mai calls from France and says that she has found an English producer who is interested. She is already in the process of translating the script into English. “We WILL make this film,” she says confidently. On February 7, I pick up Mai’s English script at Bengt Forslund’s office. To my delight, I find that she deleted some superfluous and very expensive sections in this version. This is the best thing I’ve read. And Maja now feels very close. I write a few enthusiastic lines to Mai. We speak again on the phone. Mai tells us that she received an offer from England. She is in the process of writing the screenplay for an early Karen Blixen novel (“The Angelic Avengers”, 1944). Mai was happy to devote herself to Blixen for a while and earn some money from it. Now it is almost May, and still no word from Ingrid Edström about the new English script.

When I get home to Sigtuna after midnight after playing in “Remember the City”, an express letter is waiting from Mai who is in Madrid. She begins by writing that she is on a committee to screen the thirty best European films 1925-1990. After a few days at home in Le Mazel, she is going to the Cannes festival, invited by a French female producer. As it happens, there might be a French-English production of Maja – and Jeanne Moreau is interested in the role! Mai will meet the producers and Moreau in Cannes. “Yes, well, I’m very sorry for you and hope you can try to understand my problem. I just have to make Maja! And somewhere,” Mai continues, “I feel a little Schadenfreude at being able to point my nose at the Film Institute. They have certainly not been on my side. Also, they didn’t understand the project, didn’t see the humour… Damn rude fucking Swedes, who don’t want to stand up for you! I’m too troublesome for them. The Girls have become a cult film and is always out in the world, Amorosa as well. At The Swedish Institute they say it’s Ingmar’s and my films that travel the world, but even this won’t help when you want to make a new film. Then they get terrified again. Damn, I want to start swearing like Ingmar…”

The next morning I wrote to Mai that her letter had dismayed and disappointed me. Would Maja become French? Isn’t “Rapport från en skurhink” a highly Swedish story? What about Bofors and the Swedish double standard? Sven Nykvist has just made a Swedish shoot with American producer money (The Ox, 1991). If the French and English producers like your script and believe in you as a director, surely they also respect your judgment when it comes to the casting?

Mai was supposed to call me when she got back from Cannes. I tried to reach her but gave up after a few weeks. At the end of May, Mai calls, on her birthday, sounding pitiful. She said nothing was decided. I said that I read an interview in Aftonbladet where Mai said that Moreau will be a wonderful cleaning lady. And that the film will be made in England.

I then learned from Ingrid Edström that the female French producer did not know that Mai had written the role for a Swedish actress who had been attached. Ingrid had brought up the moral aspect of letting the role go to Moreau, but Mai had claimed that I was completely on board. The French producer also thought that the film could well be shot in Sweden – and Moreau dubbed into Swedish.

The months passed. One autumn day I called Le Mazel. Found Mai depressed. An unusual condition for her. She hadn’t opened my last letter. Still didn’t know how or if the movie would turn out. But was happy that I had called. It felt like a reconsiliation.

In 1992 I visited Mai again. Together with Sheila La Farge, Ulla Ryum and Ellen Castberg from Copenhagen, we were going to celebrate Christmas in Le Mazel. As always, she was concerned about her financial situation. I myself worried about her work situation. All the different film scripts that she didn’t get to realize as a director! I had just read her English script for her book “Bird of Passage”, which she hoped to shoot in Holland this summer. And the Maja Ekelöf story, which she turned into “Three Maids in Europe” and wrote several different scripts for, she also didn’t know if she would get to do.

My resentment at the betrayal I experienced when she replaced me with Jeanne Moreau as Maja Ekelöf is done and over with, thank Godness. I got a painful reminder when Mai said one evening that Moreau is no longer an option for the role. Also, Mai had seen her on a TV show recently and thought she had aged in a way that didn’t fit the cleaning lady role. As if Moreau ever fit as Maja Ekelöf! Other than as a crowd-pulling name, of course…

In March 1993, Mai becomes ill and is operated on for a cancerous tumour in April. During the summer that followed, Mai was fine. In the autumn, she came to Sweden to try to get the Film Institute interested in “Bird of Passage”, which she hoped to start filming in the summer. She was also going to talk about a script she wrote based on Sara Lidman’s short story about a pine tree. The past year with surgery and mental experiences she had in dreams and in contact with the medium Nanette had been the most amazing of her life, she said. On All Saints’ Day, I drove Mai to Arlanda. The intention was that she was supposed to return to Sweden after a few weeks. But that did not happen. The last thing I saw of her was her pulling the luggage cart with all her heavy bags. She always travelled with more luggage than she could carry. Some time later, Mai told me on the phone that she had been informed that a new tumour had started to form. The doctor had said she only had six months to live. “But that won’t happen,” said Mai triumphantly. She would fight this tumour with meditation, visualization and healing. We kept in touch by phone during the winter. In one of the conversations, she told me that she’d been “operated on” by a healer. He had removed the tumour, Mai said.

On March 18, I was in my daughter Anja’s apartment to rest between the morning radio rehearsals and the evening performance of “Uncle Vanja” at the Boulevard Theater. I turned on the television and there, to my dismay, I heard the news that Mai Zetterling had died in London.

To her son Louis, she had said, when she finally accepted that she was going to die: “I have so much to do on the other side!” That sounds like Mai. Living in illusions. A strength when it comes to acting, to get into the illusion, into the character. As a writer and director, it is important to stubbornly stick to your vision, to realise it. Mai was happy to put the more or less finished manuscripts into the hands of her friends. I don’t think she expected criticism, just support for her continued writing. I probably haven’t emphasized enough about Mai’s obsession when she worked. Both during the script writing and during the time of shooting. “You can do anything you want,” she often repeated. That was her motto. An unusual, courageous and remarkable person, that’s for sure.

Written by Inga Landgré (2016)

(Translated by Jan Lumholdt)