Who was Harriet Bloch? With the exception of a few silent film nerds, her name is virtually unknown nowadays even though she was the most successful and prolific Danish screenwriter of all time. During a short time span of just 14 years – between 1911 and 1925 – she succeeded in selling 95 scripts to the booming Danish, German and Swedish film industries. At that time, her name was so famous that film posters and ads used it for advertising. However, her fame was a fleeting one, and Harriet Bloch vanished from film history already by the middle of the 1920s, soon to be more or less forgotten. Her astonishing as much as ephemeral career calls for explanations: What was her cultural and social background? How come she began to write scripts in the first place and how did she manage to establish herself as one of the leading screenwriters in her time? What were her topics? And what were the reasons she stopped writing in the middle of the 1920s, never to resume it again with the exception of a few radio plays in the 1930s?

In order to answer these questions, one can consult an abundance of sources: As far as this researcher knows, 64 of her scripts still exist in the archives of the Danish and Swedish Film Institutes. Additionally, one can draw information from posters, letters, advertisements, tax and census documents, even a taped interview with her from 1962. A card box full of contracts, letters and Bloch’s own listings of her scripts and royalties exists in the possession of Bloch’s family. The big drawback, on the other hand, is the archival situation concerning the films based on her scripts –just a few of them survived in more or less complete shape.

Considering these ample sources, one might ask why research on Harriet Bloch is so scanty – does it have to do with her being a woman, being a part of a tradition of women-in-film which a predominantly male-oriented cinema history tends to ignore? This might have contributed, of course, but the reasons are more manifold: First, doing empirical research on Scandinavian silent cinema is not exactly a mass enterprise in academia anyway, and second, screenwriters are in general hardly being paid attention to in cinema history. For a long time, screenwriting was considered to be a rather tedious subject in cinema studies. As a genre, the film script is ultimately characterized by its functionality, being a necessary step in the fabrication of the final product, the film. Or, as Birgit Schmid put it: »The function of the script text is its disappearance.« And this is not only true because of its protomedial status, but also on other levels: Usually scripts are not published, but are – at best – stored deep down in the vaults of the archives: Talking about the Danish film industry for example, a total amount of 1.574 Danish fictional films before 1920 contrasts with just five published scripts of these films. Contending for the ›authorship‹ of films, other professional groups like directors, actors or even camera men diminished the importance of screenwriters for film production in interviews and memoirs. Furthermore, screenwriters were not recognized as ›real‹ authors, they lacked institutional acceptance from other authors. Writing scripts did not qualify for admission to the official authors leagues which in turn meant that scripts were not registered as ›literature‹ in bibliographical works of reference. Accordingly, scripts and their authors later on vanished in the disciplinary gap between cinema studies and literature studies.

To put it in a nutshell, scripts – and their authors – tend to be invisible in cinema studies as well as in the cultural memory. This invisibility is not per se gender-related. Or perhaps it is, but otherwise than one would think in the first place: Thanks to feminist cinema researchers we know more about female screenwriters than about male ones when we keep in mind that female screenwriters were a minority among the screenwriters.

This statement may sound odd, because once in a while you can read that scripts from women account for a considerable, up to 50% amount of all scripts during the silent era. This might be called the ›novel analogy thesis‹: Because of women writers embracing the novel in the 18th century as a popular genre which did not require extensive formal education to master, it is assumed that the same happened when writing film scripts became a mass enterprise in the 1910s. The thesis amounts to the assumption that it was far easier for a woman to position herself successfully in the emerging field of screenwriting than to gain acceptance in the established field of ›literary‹ writing. However, the argument is anachronistic to begin with (as the women writers’ position around 1910 was quite different from the 18th century), and it lacks empirical proof. As far as I know, the only statistical analysis of this question ever made is my work done on the Danish film industry until 1918. Talking about 1.238 film scripts used or bought by the Danish film industry between 1906 and 1918 – which is pretty close to the number of films produced –, these were written by 397 authors. Among the Danish authors, just 20% of them were women, and among the foreigners the percentage is even slightly less: 18%. However, one should bear in mind that these numbers just account for the screenwriters who actually managed to sell scripts. The percentage of women writers among the creators of those approximately 3.000 scripts a year which were sent to the Danish film companies during the heyday of Danish film production around 1913 might have been higher, but most likely not exceeding a third of the writing community.

Screenwriting as a Career in the 1910s

Born in 1881 in Kolding close to the German-Danish border at that time, as the daughter of an architect, Harriet Bloch grew up with four sisters. How well-known the family must have been illustrates an ad from 1911 for Bloch’s first film in a Kolding newspaper which mentions the name of the screenwriter. That was quite an exception at the time and the reason is plainly her local origin. At the age of twenty, Harriet Bloch moved to Copenhagen. Family talk has it that she more or less emigrated to Copenhagen to get away from always having to take care of her younger sisters. Soon afterwards, she married a succesful and handsome mechanical engineer in 1902. The couple soon got offsprings: Harriet Bloch gave birth to sons in 1903, 1904, 1906, 1907 and 1909, then to one girl in 1912 and finally a last son born in 1927. The family was well-off; according to the census from 1916 the Blochs lived in a rich villa area in the north of Copenhagen with two female household employees living in the same house.

In the taped interview from 1962, Harriet Bloch maintained she started writing film scripts after having seen Urban Gads film Afgrunden with Asta Nielsen in the leading role. After her first script’s rejection by the producer of Afgrunden, she sent the script to a company named Panoptikonteater. Both initial addressees are significant, as they tie in Harriet Bloch’s entering the sphere of film production with the movement of ›art films‹ at that time and help to answer the question of how a woman from a rather bourgeois home could start writing for the film industry which was still struggling to gain cultural acceptance. Panoptikonteater was the result of a Danish attempt to establish a so-called ›literary‹ film production company which should produce high-brow-films like the ones the French Film d’art-company and similar enterprises came up with. The intention was nothing less than to both produce and exhibit films compatible with bourgeois conceptions of art, thereby reforming the film industry. Although the production company just managed to produce ten films before going bankrupt by the end of 1910, the enterprise had a lasting effect on Danish film production: On the one hand, Panoptikonteater became for a few years the exhibition site for high-brow-films. And on the other hand, the widely discussed intention to ›upgrade‹ films in a bourgeois perspective attracted a new class of creative people to the film – or, to look at it another way, made it possible for these people to engage in the film business without losing their symbolic capital. Among them were for example renowned authors like Herman Bang, stage actors like the later-on-famous Valdemar Psilander – and not least Harriet Bloch. On the whole, the Danish cinema became a very bourgeois cinema, compared with its competitors. Significantly, the notion of author’s films (›Autorenfilm‹), that is producing film versions of well-known literary works and advertising with their well-esteemed authors, originated in the Danish film industry in 1912 – and significantly, Harriet Bloch wanted to be a part of it in 1913, offering her services to adapt Jonas Lie and Henrik Ibsen for the screen.

Although her first script was rejected, Bloch soon tried her luck again with a new one, and this time Nordisk Filmskompagni, the by far largest Danish film company at that time, bought it for 50 crowns. Quickly Bloch seems to have learned the tricks of the trade: In 1911 she sold three more scripts, 11 in 1912, 14 in 1913, 16 in 1914, 13 in 1915, 21 in 1916, and her income grew accordingly from 377 crowns in 1911 to 6.000 crowns in 1916. In Denmark at this time, a middle class family could live on 4.000 crowns a year, so 6.000 crowns was a staggering amount. In the 1916 census, Bloch proudly stated her profession to be »filmsforfatterinde«, female screenwriter. How did she become so successful? How did she earn her reputation of being a truly professional freelance writer – something the Danish later-on film maker Carl Theodor Dreyer, at the time working in the script department of Nordisk Filmskompagni, already stated in an article in 1916, and when Ole Olsen, the founder of the Nordisk Filmskompagni and the tycoon of Danish film industry, wrote his memoirs in 1940 he underlined that Bloch’s scripts usually could be used for shooting with just a minimum of revision necessary.

The first script Harriet Bloch sold in 1911 bears a very unusual commentary: »Fruen vil gerne se Prøverne« – »The lady would like to see the rehearsals«. Right from the beginning, Bloch wanted to know as much as possible about film production in order to write suitable, which means: saleable, scripts. In the interview from 1962, she mentions that in the beginning of her career she was always welcome in the studios to look at the shooting of films.

A much bigger challenge was to understand the limitations imposed by the censors. These censorial limitations were an important part of the set of rules of screenwriting, and normally both freelance writers and established writers from outside the film industry had severe problems accepting these limitations. In 1911 and 1912, quite a few of Bloch’s scripts were rejected because the companies were afraid of censorial problems. In 1911, a script with the title I Kvindevold (In the Power of Women) is sent back to her with the commentary that »the scene in the bedroom is too powerful«. Unfortunately, the script no longer exist – one would have liked to take a closer look both at the script and the scene. Other commentaries from 1912 criticize for example the throwing of vitriol acid in the end of a film, which »without doubt would be banned by the censorial authority in all civilised states«. Another script was sent back to her »because of the following censorial reasons: burglary, encouragement of a crime, warning a criminal, in short: the police would say: The bad prevails! and would forbid the film straightaway«. Such reasons for rejections end by and large in 1913 which indicates that Bloch at this time had mastered the censorial set of rules.

Another part of Bloch’s professionalism was her realization that her script was just a brick in the production of a film. This meant on the one hand that she did not hesitate to rework her scripts when necessary, even coming to the production site in Valby, nowadays a part of Copenhagen, to do so when the directors reckoned this to be necessary while already shooting the film. But she was also professional enough not to complain about alterations in her script made before or while shooting the film. As she said in 1962: »Det blev jo ikke mine film i og for sig når de kom frem« – »Actually, those were in itself not my films when they came out«.

Harriet Bloch sold most of her scripts to the Danish Nordisk Filmskompagni in Copenhagen, but as a freelance writer she even employed a strategy of diversification when it came to selling her scripts. The letters in the family’s archive show that she was in contact with no less than 19 film companies both in Denmark, Germany, Sweden and the USA. Obviously able to write in German, she sold seven scripts to German film companies until 1913. In 1915, she established ties with Svenska Biografteatern and thus became one of those Danish script writers the Swedish censor Gustaf Berg complained about in 1917 because in his opinion, the omnipresent Danish scripts did not allow enough room for Swedish ones. After selling two scripts to Svenska Bio, Bloch inquired what kind of scripts Svenska Bio would especially be interested in, and after receiving this information marked as confidential she produced four more tailor-made scripts the company bought at once. At this point, Svenska Bio wanted to tie Bloch closer to the company: She was invited to a screening of Kärlek och journalistik (Love and Journalism) in the company’s local office in Copenhagen, and Bloch and Svenska Bio entered a contract about 500 crowns per script. In September 1917, this contract seems to have been no longer valid and the cooperation came to an end, probably because of Svenska Bio’s shift in production policy.

Stagings Stars and Doing Gender

At the heart of Harriet Bloch’s success is of course her ability to write narratives which people wanted to see on screen in the first place. Generally, Bloch excelled in a genre you might call bourgeois comedy, usually with quite a distinctive gender twist and an erotic subtext, sometimes reminiscent of later screwball comedies. Women were a large proportion of the cinema-going audience, if not the majority, and many of Bloch’s scripts seem to address a female audience – not by taking a suffragette’s stance, but by modestly making fun of patriarchic behaviour. Den nye Husassistent (The New House Assistent), even called De Ægtemand! (The Husbands) from 1915 is in this respect quite a typical Bloch comedy: Two merchants exploit the absence of their wifes to go out at night and have a binge with a girl, not least by dancing – as it says in the script – »an original three-person-tango«. But nemesis has it that the next day the girl is employed by the wife of one of the merchants as the new house assistent, and the merchant has to pay the girl in order to get her out of the house again, sending her over to his buddy so that he too has to pay her off. So the guys’ night ends with quite a financial punishment for the two merchants, while the girl gets the bone, so to say: Although she is shown as easy-going, pleasure seeking, smoking and probably doing other things as well which she would normally be condemned for, in this script she is not being punished for her immoral behaviour, but explicitly rewarded. The still existing program leaflet underlines that in the end the girl is the true »able businessman«, not those two husbands who suddenly hide under tables and have to be saved by the girl from their suspicious wives.

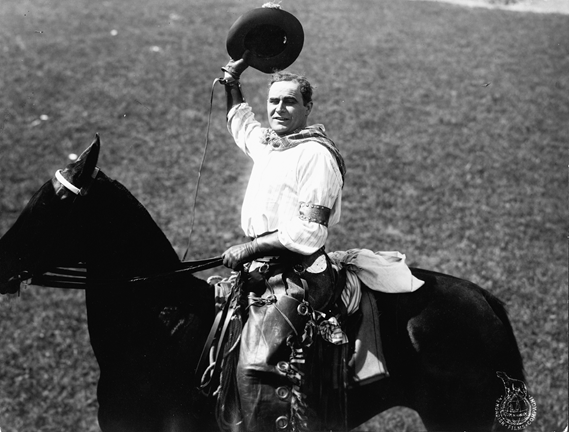

Another speciality of Harriet Bloch was to write scripts as star vehicles. Her definite breakthrough as a screenwriter in 1913 was not just a result of her professionalization, but also had to do with a change in production policy. The actor’s celebrity became increasingly important in the marketing of films, which meant that the companies needed scripts in accordance with the respective star persona. Nordisk’s biggest star was Valdemar Psilander, and Harriet Bloch became the screenwriter who wrote more scripts for Psilander during his last three years of film production than anybody else. In the interview from 1962, she remarked that the scripts she liked best were the scripts she wrote commissioned for Psilander. When Psilander started his own company in 1917 shortly before his death, Bloch supplied him with scripts, asked for by Psilander himself who valued her ability to write tailor-made star vehicles.

Manden uden Fremtid (The Man Without a Future) is a perfect example for this close cooperation between Bloch and Psilander. According to Bloch’s own statement in the interview from 1962, she once had asked Psilander which role he himself would wish for, and he had answered that he would like to play a cowboy – so she wrote a cowboy film for him. Actually, the final film is very close to Bloch’s still existing script; just a few scenes in Bloch’s version were dropped in the shooting script and the film.

The knocked-together plot cannot boast of originality and is afraid of neither a sudden deus-ex-machina lordship or a dramatic device like the belated letter, which serves to clear up a muddled situation at the last minute. Yet seen from the perspective of the requirements of a star system, such a banal plot is a perfect vehicle as its predictability does not distract from the star Psilander who is always at the center of attention. The script stages Psilander in different social roles, providing him with ample opportunities to put on show different outfits and modes of behaviour: as an unrefined American cowboy, as an English lord, and in Bloch’s script even as a car mechanic, though this scene did not make it into the film. Thus Psilander’s heterosexual masculinity is visually staged very prominently, not at least by the leathern cowboy outfit and the difference both to the girl’s older father and the most refined, decadent-looking competitor. In this film, Psilander exudes eroticism already because of his bodily appearance, but this eye-catching erotic dimension is already preconfigured in the script, albeit – in the abscence of pictures – on a narrative level. Bloch introduces Psilander’s character Percy in the beginning of the film in erotically-charged situations and spaces. To begin with, he is a cowboy, connoting a sphere of natural animality while being an outsider in the bourgeois world with its erotic and sexual restrictions. Percy meets his later wife Grace the first time when she is »in white underskirts«, doing her morning toilet out on the plains – definitely not a socially acceptable way of getting to know each other. Social rules are generally suspended in this space where Percy rules, »the picturesqe cowboys dance wildly with the fine strange ladies«, as the script states, and Percy and Grace take a little ride in the moonlight, both on the same horse – the sexual subtext is obvious enough.

It is possible to detect a prefeminist agenda even in The Man Without a Future. In spite of the plot’s banality, it tells a ›girl meets boy‹ story rather than a ›boy meets girl‹ story. Bloch’s The Man Without a Future is at heart a gender-inverted cinderella tale, using two omnipresent figures of popular culture in the 1910s: the cowboy and the dollar princess (as Bloch explicitly calles Grace in the script, thereby implicitly pointing at that the fairy tale prince becomes a princess in her version). To evoke such an archetypical narrative scheme while at the same time subverting it and bringing it up to date was certainly a clever move by Bloch.

The End of Freelance Screenwriting and Quiet Afterlife

In the beginning of 1918, Harriet Bloch’s streak of success came abruptly to an end, although she still sold a few scripts until 1925. The reasons are manifold. In Denmark, her main buyer Nordisk Filmscompagni cut down the production from a peak of nearly 150 feature films a year in 1914 to less than 10 in the 1920s. In Sweden, the change in production policy made Bloch’s favourite genre of shorter comedies unattractive. Sending back a script in 1917, Svenska Bio commented that »the narrative belongs to a genre which we now have given up«. Even in Denmark, shorter bourgeois comedies were not any longer in demand. One of Nordisk’s own story editors wrote to Harriet Bloch in the end of 1917: »Incidentally, I have to inform you that ›affable‹ comedies are not what the audience wants to see. One asks for a bolder kind of humour, – grotesque characters and crazy ideas«. It is easy to guess what this remark was referring to: films featuring comedians like Charlie Chaplin or Harold Lloyd, made by directors like Hal Roach or Mack Sennett with his Keystone Cops – this kind of American comedy conquered even the European screens from 1917 onwards.

With her two main markets lost for her scripts, Bloch once again turned to the German market. Using her connections with Danish actors and film directors who had emigrated to Germany during or after the end of the First World War, she managed to sell five scripts to the booming German film industry in the next years. However, these successes were just superficial, as they would not have been possible without Bloch’s personal connections. The letters from the German film companies in the possession of the Bloch family illustrate the problems Bloch encountered very clearly. One problem was the language: The scripts Bloch had sold to German companies from 1911 to 1913 had been rather short subjects, but scripts around 1920 were lenghty, easily longer than 100 pages, and writing such scripts in German exceeded Bloch’s language capabilities. Her scripts now had to get translated into German, which of course was a sincere competitive disadvantage.

But the main reason for the end of Bloch’s career as a screenwriter was a more structual one: For freelance screenwriting, the game was over. As Bertolt Brecht put it: »The film script is a kind of extemporaneous script. The poet as an outsider does not know the needs and resources of the respective studios. No mechanical engineer projects a complicated water installation to have in stock hoping that once a company can be found which needs exactly this installation.« Film making had become a very complex business, and living in a villa in the north of Copenhagen was too far away from the film production sites in Berlin. In Copenhagen, Bloch had been able to attend the shooting and talk with the persons in charge, but that was out of question concerning Berlin.

Furthermore, Bloch’s rather simple scripts did not agree with the new mode of film making after the First World War. In Bloch’s scripts, a scene was simply defined as a narrative unity, and no attention was normally paid to cinematography. These scripts worked fine as long as film makers mainly used the European mode of staging in depth, that is as long as breaking down a scene in several shots was not deployed as the main narrative device. Instead, one rather used careful arrangements of actors and movements in the depth of the cinematic space. But after the end of the First World War, American editing techniques and the powerful device of the close up became more common, and this implied a different kind of screenwriting – a kind Bloch was unfamiliar with. She was professional enough to ask the German company which had bought one of her scripts and turned it into the Murnau-Film Der Gang in die Nacht to see the shooting script, written by the famous scenarist Carl Mayer. But writing such shooting scripts implied being close to the film production and a lot of technical knowledge about how to work a camera. The era of freelance screenwriting had come to an end.

In the 1930s, Bloch wrote a few radio plays which do not seem to exist any longer. In the same decade, she bought an apple plantation together with one of her sons in the North of Sealand and settled down as a farmer until her death in 1976, ninetyfour years old. Her career as a screenwriter was not completely forgotten, but references to it became rather sporadic: In 1941, the Danish author Edith Rode published a Golden Book about Danish Women (Den gyldne Bog om danske Kvinder), which even had a short entry about Harriet Bloch. Twenty years later, a journalist named Arnold Hending interviewed her about her work for the Danish film industry and called her jokingly »Denmarks Selma Lagerlöf«, thereby drawing a – rather overstretched, one might add – parallel between Lagerlöf’s importance for the Swedish Golden Age film production and Bloch’s for the Danish one. As already mentioned, the Danish film museum conducted and taped an interview with the 81 years old lady in 1962. Pioneers of exploring Danish cinema history like Marguerite Engberg mentioned her of course when writing about the Golden Age of Danish silent cinema, but strangely enough, the first wave of feminist revision of the canon overlooked Harriet Bloch completely: She was neither mentioned in the Nordic Women’s Literature History nor in the Danish Biographical Encyclopedia of Women (Dansk kvindebiografisk leksikon) with its more than 1.900 entries.

Stephan Michael Schröder

Prof. Dr., University of Cologne