“I planned to spend a year in Peru, but I’ve been there a while now,” says Eyde, smiling. She is in Oslo to deliver footage to the National Library after many years of filmmaking.

Unlike modern film directors who often depict individuals and their psyche, Marianne Eyde makes films about large groups of people. In You Only Live Once/La vida es una sola she focuses on the farmers in a rural village, the government forces and the militant communist Shining Path group. For Eyde, making film is a means of getting closer to people, and her feature films are a result of a broad collective collaboration.

After arriving in Peru Eyde found a job in a kindergarten, even though she believed the job should go to someone local.

“I told them I wouldn’t take anyone else’s job, and quit after three hours,” she says with a smile.

Eyde took a part-time job in a travel agency, and used her free time to organize activities for young people in the poor district of Comas. She married in 1969 and later had a daughter. In the evenings she did media studies at the university in Lima.

During her studies, she found a job in the production company Producciones Cinematograficas del Peru, which made short films. She worked partly as a researcher, but Eyde was not satisfied with the arrangement.

“Every time we discussed subjects, they chose the ones I liked the least. So I started my own company. I took out a bank loan and signed a co-production agreement with Producciones Cinematograficas del Peru, with them paying for laboratories and me adding personnel. Peru had a favourable law on short films, which gave a tax rebate on short films that were screened as previews to the main features at the cinemas. If you made four short films a year, you could live on that,” Eyde explains.

By now Eyde had her own film company, a co-production agreement, and perhaps most importantly the freedom to choose the subjects of her films. There was, however, something missing: if she was to make believable films, she needed technical know-how as well.

“Nowadays there are a lot of female technicians in South America, but at the time, especially if you had children, you were told this may not be the right line of work for you. In 1976 I went back to France and got a job as a trainee at Alga Samuelson in Paris.”

Alga Samuelson was a company that hired out technical equipment for film productions, and the job was a strategic choice on Eyde’s part. While her daughter was in kindergarten, Eyde could get in touch with customers and offer her services as assistant on their film projects. That way she learnt camera work, editing and sound finishing. She also gained experience in laboratory development for the company Éclair. Also at Alga Samuelson she met the French cinematographer Anne Khripounoff, who would later become a great support.

During her time in Paris she also met Jean-Marie Lavalou and Alain Masseron who developed the Louma camera crane in the 1970s, a remote-controlled telescopic crane used widely for complex single shots. With Lavalou, Eyde travelled around demonstrating the crane, and she particularly remembers a customer who visited Biarritz in 1976 to see the new technology.

“Jean-Marie had heard that Spielberg wanted to see the crane. He was going to be there at ten o’clock and the three of us were ready to assemble and dismantle the crane as quickly as possible. But by noon there was still no sign of Spielberg, so Lavalou said we should celebrate anyway. So we celebrated with a nice lunch,” says Eyde.

Spielberg turned up after lunch. The demonstration went very well, and Spielberg took the crane back to Los Angeles.

Eyde’s educational trip to Paris was nearing its end, but she had one thing left to do: before taking her flight back to Lima, she bought a used 16 mm Éclair camera which she refurbished in the mechanical workshop at Alga Samuelson.

Back in Peru she carried on producing short films, but was increasingly worried that the law giving tax rebates on short films would not last. Eyde therefore focused instead on longer projects with the films Casire (1980) and Alpaca Breeders of Chimbova (1983), which she directed, wrote and shot with her 16 mm Éclair camera. Casire was also her main project at the University of Lima. She worked with major distribution companies like Gaumont, which sold Casire to Japan, Australia and Canada – although this particular collaboration turned out not to be that profitable.

“You can’t work with big companies. Once you see the accounts you virtually owe them money, so I said, ‘Please give me back the rights before I owe you more money’.”

In the early 1980s, Eyde started working on the feature film Los Ronderos (eventually released in 1987). On board was Anne Khripounoff, whom she had met at Alga Samuelson. Khripounoff was one of France’s first female cinematographers, with experience form being a camera assistant on The Man Who Loved Women/L’homme qui aimait les femmes and The Green Room/La chambre verte (François Truffaut, 1977 and 1978), and as cinematographer on I’m Shy, But I’ll Heal/Je suis timide… mais je me soigne (Pierre Richard, 1978).

“Thanks to Khripounoff and her planning, Los Ronderos reached a huge audience. People arrived in coaches and lorries. We began in the provinces. The income from the first town paid for the marketing in the next. The first cinema owner was so pleased on the first night that he started drinking, and carried on for the rest of the week. I had to staff the cash desk while the women’s committee checked the tickets.”

How did you get the word out to so many?

“We got help from the farmers’ organization, which was very powerful at the time.”

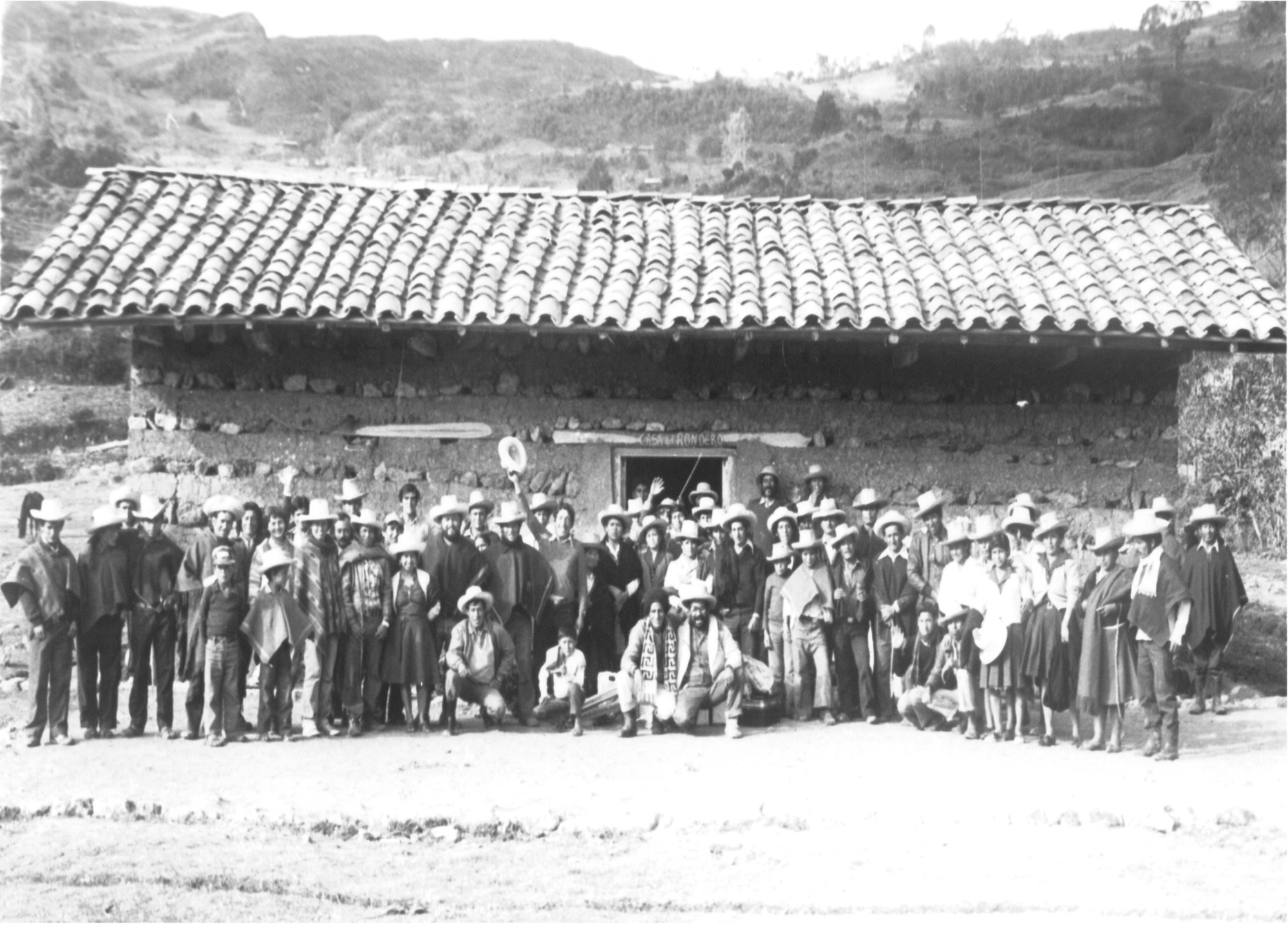

The farmers’ organization was also involved in the actual production of Los Ronderos, from the script that is based on the farmers’ own stories, to the casting of actors, who were also farmers. The organization represented the entire district, and this meant that all villages had to be represented in the film – something that entailed a lot of long treks for Eyde who assumed the task of training the actors.

“One day I told my daughter we were packing our things and going back to Lima because I was fed up. She said, ‘But mum, really. You’ll be leaving the very people who are supporting you. Are you just going to say you’re fed up and leave?’ ”

Los Ronderos premièred in 1987 and was poorly received by critics. It was shown at the film festival in Havana, where people said it should never have appeared. Among the peasant farmers, however, it was a roaring success. Half a million Peruvians saw the film, and Eyde could pay off her bank loan.

“I think the film was a success because it was a collective effort from the word go. A lot of the eventual film was included in spite of me, there was a lot I hadn’t planned or intended. I think that as so many people were involved in the production, a lot of people felt that it was about them.”

And it got you free of debt?

“It got me free of debt, but that was thanks to half a million viewers,” Eyde explains.

Eyde’s second feature, You Only Live Once/La vida es una sola, was released in 1993. As with Los Ronderos, the film is based on real-life conflicts that affect the peasant farmers of Peru.

“I made You Only Live Once because I was so angry. I’ve always travelled round the country a lot. I went by lorry, bus, boat and on horseback, but in those days there were places I couldn’t go because people got stopped by the government or the Sendero Luminoso, (the Shining Path).”

The Shining Path was a militant communist group that progressively recruited young people at several Peruvian universities in the 1960s and ’70s. In 1980 the group started a guerilla war in the Peruvian highlands. As a result, the struggle between the Shining Path and the governing powers became partly a fight for the different regions, and this affected the farmers. Anyone who tried to remain neutral was seen as an enemy, both by the government and the Shining Path.

“People fled the villages and sometimes walked up to 800 kilometres to escape the Shining Path. Many didn’t dare say where they came from.”

Due to her earlier film projects, Eyde had a large network of contacts among the local farmers. She hired an acquaintance from the farmers’ organization (which was still powerful in Peru), and interviewed farmers and soldiers from the military.

“We ended up with something like a thousand pages of interviews.”

She hired a dramatic advisor, and together they wrote a screenplay based on the interviews.

“Every sentence in You Only Live Once was something someone said in the interviews. The dramatic advisor was so afraid when the film was released that he didn’t want his name in the credits.”

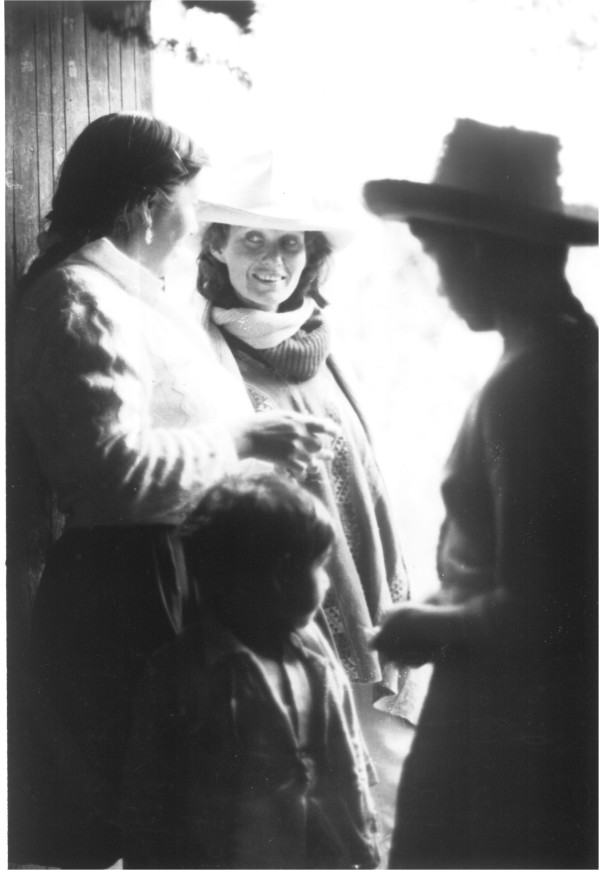

With the screenplay finished, Eyde needed somewhere to shoot the film – somewhere not controlled by the Shining Path. She dressed herself in poncho, hat and scarf, and set off into the Peruvian highlands looking for a village to form the backdrop to You Only Live Once. She was eventually contacted by someone who had previously worked in cultural activities for rural areas. He had heard that Eyde was looking for a shooting location and offered his services as a guide. Eventually, they found a place in the mountains that was perfect.

“It was out of the way of the Shining Path, an isolated area with little outside contact. It was also at high altitude, so I had natural light all day long. We did our casting by reading the script out in Spanish and in the local language to the Quechua people who live in the Andes. We borrowed the school during the holidays to live in, and I had showers installed.”

Eyde hired actors who spent time with the farmers, so the farmers learnt something about acting while the actors learnt something about farming.

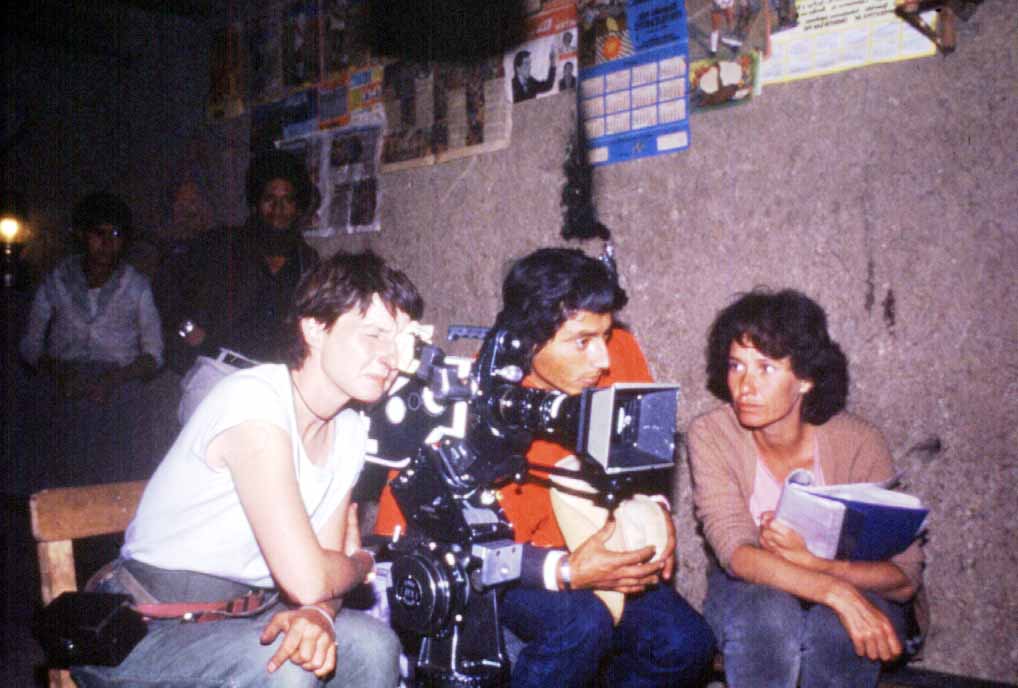

With a screenplay, cast and location, Eyde then needed a cinematographer, although she didn’t use Anne Khripounoff who had shot Los Ronderos.

“I think Anne felt very hurt, but I couldn’t have another foreigner in the village, it would attract too much attention. I thought, ‘Who can I use who can tolerate my working methods, sleep in dormitory conditions and so on?’ I asked a few friends, and they recommended César Pérez. Pérez, from Peru, was the permanent cinematographer for Jorge Sanjin Sanjinés, one of the first Bolivian directors to make film about social problems in Bolivia. I wrote to Pérez, who agreed and was a tremendous support.”

Unlike Los Ronderos, which was a great success in Peru, You Only Live Once encountered problems. No cinemas wanted to screen the film, and it was not released until a year after completion. However, Eyde had some friends who were going to a film festival in Chile. For the festival, subtitled 35 mm copies of You Only Live Once were made, and it was later shown at the Toronto Film Festival, where the distribution company Film Transit picked it up. The film ended up being shown at over 100 festivals worldwide, including Chicago, Hong Kong and Sundance.

The film had to travel without its director, however.

“I couldn’t afford to get to Sundance myself, but the film was there,” says Eyde.

(Translated by Matt Bibby)